Bringing a shark to a knife fight: 7,000-year-old shark-tooth knives discovered in Indonesia

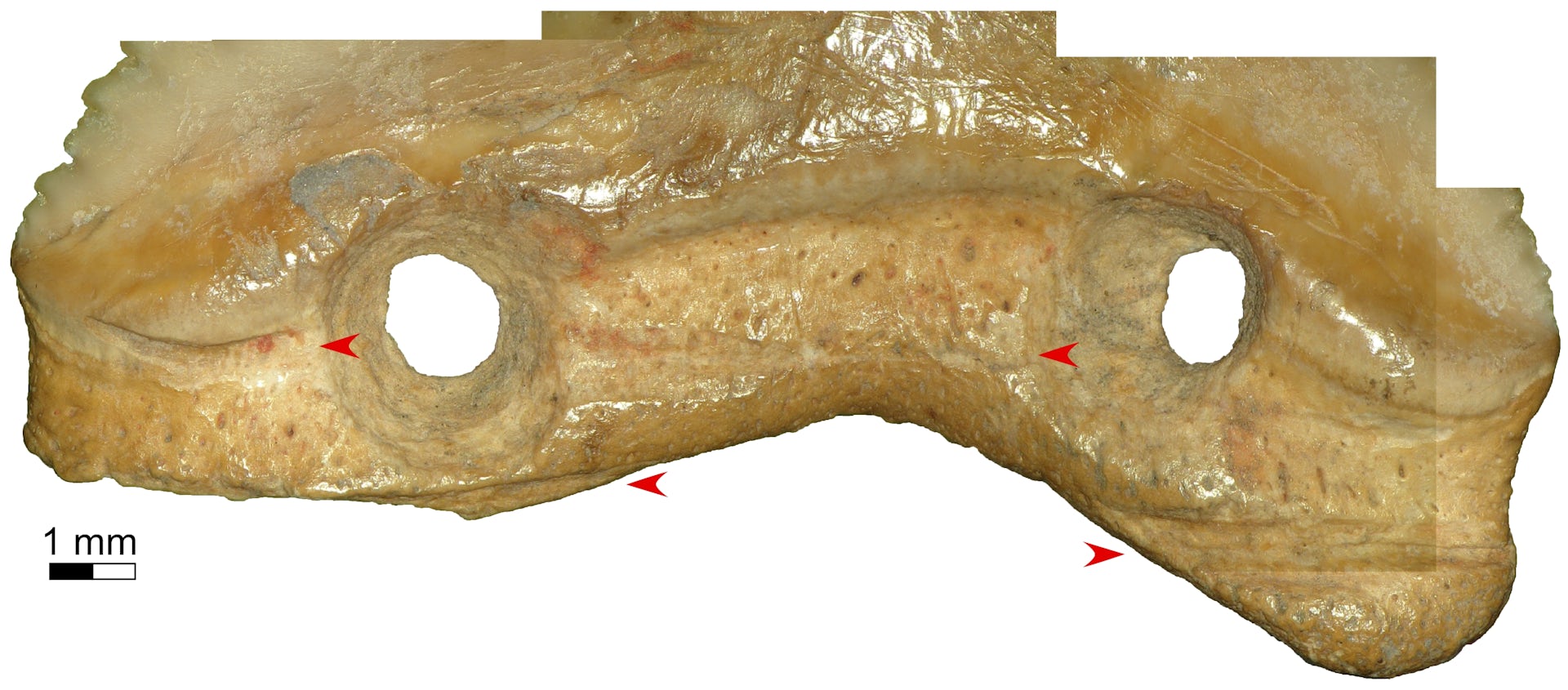

Figure 5. Use-related features of the Leang Panninge shark tooth: a) ground facet (indicated by red arrowhead) and striations on the lingual surface; b) grooves between the perforation and tooth shoulder from ligatures; c) plant fibre associated with hafting; d) cut notches along the base and grooves from ligatures (both indicated by red arrowheads) on the labial surface. White scale bars = 1mm (image c by B. Stephenson; all other images by M. Langley).

From there, apparently, the surviving humans repopulated Earth, invented new cultures and languages as they did so, forgetting all about the flood and the god who inflicted it on their recent ancestors, and invented new gods and religions, with only one small tribe remembering it all in word-perfect detail.

Apart from the ludicrously narrow genetic bottleneck this would have cause, meaning almost all the surviving species would be extinct within a few generations, there is the little problem of so much archaeology being around that would not have survived such a flood, and evidence of cultures that existed before, during and after it apparently without noticing it at all. An example is the 7,000-year-old fighting knife made from shark teeth discovered on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, which should not have been there if the Bronze Age tales made up by people who thought Earth was small and flat with a dome over it and ran on magic, that creationists think were true history and real science, actually were true history and real science.

This discovery by a team of archaeologists from Australian and Indonesian universities led by Associate Professor of Archaeology, Michelle Langley of Griffith University, is the subject of an open access paper published recently in Antiquity. Five of the authors have also written about this discovery in The Conversation. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Bringing a shark to a knife fight: 7,000-year-old shark-tooth knives discovered in Indonesia

Credit: Matthew R McClure/Shutterstock

Michelle Langley, Griffith University; Adam Brumm, Griffith University; Adhi Oktaviana, Griffith University; Akin Duli, Universitas Hasanuddin, and Basran Burhan, Griffith University

Excavations on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi have uncovered two unique and deadly artefacts dating back some 7,000 years – tiger shark teeth that were used as blades.

These finds, reported in the journal Antiquity, are some of the earliest archaeological evidence globally for the use of shark teeth in composite weapons – weapons made with multiple parts. Until now, the oldest such shark-tooth blades found were less than 5,000 years old.

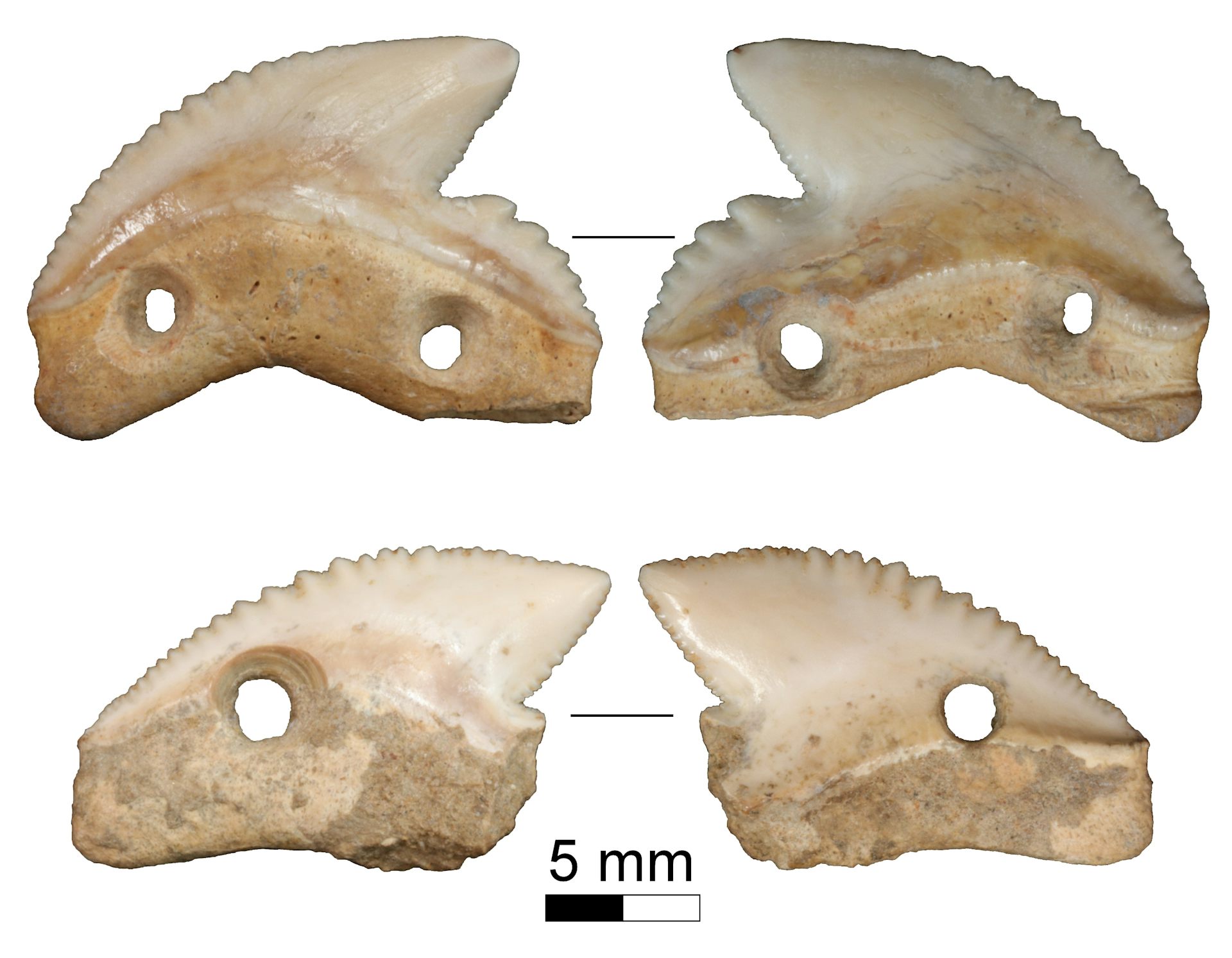

Modified tiger shark teeth found in 7,000-year-old layers of Leang Panninge (top) and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 (bottom) on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

Credit: M.C. Langley

7,000-year-old teeth

The two shark teeth were recovered during excavations as part of a joint Indonesian-Australian archaeological research program. Both specimens were found in archaeological contexts attributed to the Toalean culture – an enigmatic foraging society that lived in southwestern Sulawesi from around 8,000 years ago until an unknown period in the recent past.

The shark teeth are of a similar size and came from tiger sharks (Galeocerda cuvier) that were approximately two metres long. Both teeth are perforated.

A complete tooth, found at the cave site of Leang Panninge, has two holes drilled through the root. The other – found at a cave called Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 – has one hole, though is broken and likely originally also had two holes.

Microscopic examination of the teeth found they had once been tightly fixed to a handle using plant-based threads and a glue-like substance. The adhesive used was a combination of mineral, plant and animal materials.

The same method of attachment is seen on modern shark-tooth blades used by cultures throughout the Pacific.

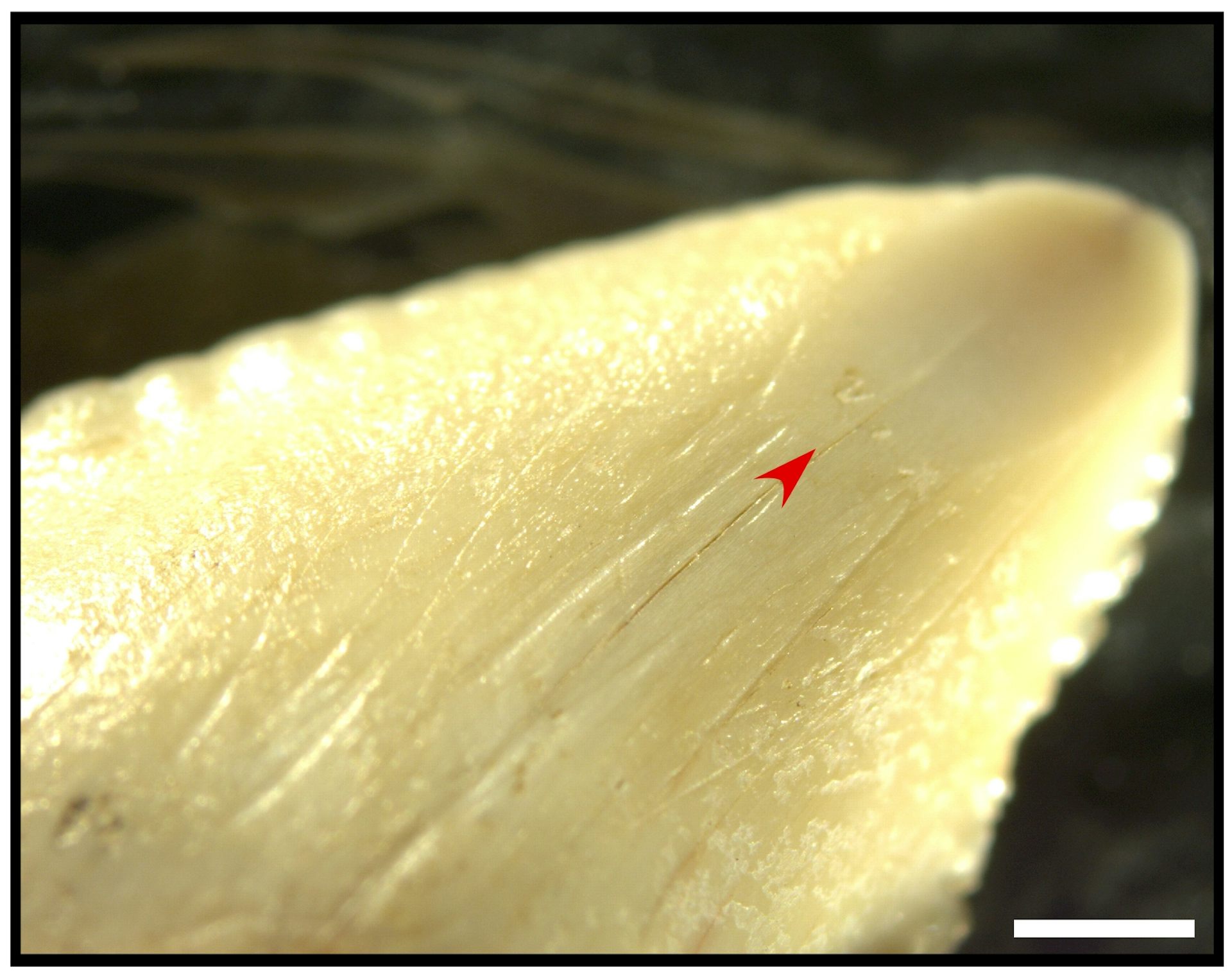

Scratches and a ground section on the tip of the Leang Panninge shark tooth indicate its use by people 7,000 years ago.

Credit: M.C. Langley

While these residues superficially suggest Toalean people were using shark-tooth knives as everyday cutting implements, ethnographic (observations of recent communities), archaeological and experimental data suggest otherwise.

Grooves and traces of red resin along the base of the Leang Panninge tooth show how the teeth were attached using threads.

Credit: M.C. Langley

Not surprisingly, our experiments found tiger shark-tooth knives were equally effective in creating long, deep gashes in the skin when used to strike (as in fighting) as when butchering a leg of fresh pork.

Indeed, the only negative aspect is that the teeth blunt relatively quickly – too quickly to make their use as an everyday knife practical.

This fact, as well as the fact shark teeth can inflict deep lacerations, probably explains why shark-tooth blades were restricted to weapons for conflict and ritual activities in the present and recent past.

Shark-tooth blades in recent times

Numerous societies across the globe have integrated shark teeth into their material culture. In particular, peoples living on coastlines (and actively fishing for sharks) are more likely to incorporate greater numbers of teeth into a wider range of tools.

Shark teeth are widely used to edge deadly combat weapons or powerful ritual blades in the Pacific. Left: a knife from Kiribati; centre and right: weapons from Hawai'i.

For example, a fighting knife found throughout north Queensland has a single long blade made from approximately 15 shark teeth placed one after the other down a hardwood shaft shaped like an oval, and is used to strike the flank or buttocks of an adversary.

Weapons, including lances, knives and clubs armed with shark teeth are known from mainland New Guinea and Micronesia, while lances form part of the mourning costume in Tahiti.

Farther east, the peoples of Kiribati are renowned for their shark-tooth daggers, swords, spears and lances, which are recorded as having been used in highly ritualised and often fatal conflicts.

Shark teeth found in Maya and Mexican archaeological contexts are widely thought to have been used for ritualised bloodletting, and shark teeth are known to have been used as tattooing blades in Tonga, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Kiribati.

In Hawai‘i, so-called “shark-tooth cutters” were used as concealed weapons and for “cutting up dead chiefs and cleaning their bones preparatory to the customary burials”.

A shark-tooth knife from Aua Island, Papua New Guinea. Red arrows highlight wear and damage caused by fighting.

Credit: M. Langley and The University of Queensland Anthropology Museum

Almost all shark-tooth artefacts recovered globally have been identified as adornments, or interpreted as such.

Indeed, modified shark teeth have been recovered from older contexts. A solitary tiger shark tooth with a single perforation from Buang Merabak (New Ireland, Papua New Guinea) is dated to around 39,500–28,000 years ago. Eleven teeth with single perforations from Kilu (Buka Island, Papua New Guinea) are dated to around 9,000–5,000 years ago. And an unspecified number of teeth from Garivaldino (Brazil) is dated to around 9,400–7,200 years ago.

However, in each of these cases the teeth were likely personal ornaments, not weapons.

Our newly described Indonesian shark tooth artefacts, with their combination of modifications and microscopic traces, instead indicate they were not only attached to knives, but very likely linked to ritual or conflict.

Whether they cut human or animal flesh, these shark teeth from Sulawesi could provide the first evidence that a distinctive class of weaponry in the Asia-Pacific region has been around much longer than we thought.

Michelle Langley, Associate Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University; Adam Brumm, Professor, Griffith University; Adhi Oktaviana, PhD Candidate, Griffith University; Akin Duli, Professor, Universitas Hasanuddin, and Basran Burhan, PhD candidate, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AbstractOther than lying about science or blatantly misrepresenting it, I've yet to see a coherent explanation for why so much of Earth's history pre-dates the creation cult's 'Creation Week'.

Although first identified 120 years ago, knowledge of the Toalean technoculture of Middle Holocene Sulawesi, Indonesia, remains limited. Previous research has emphasised the exploitation of largely terrestrial resources by hunter-gatherers on the island. The recent recovery of two modified tiger shark teeth from the Maros-Pangkep karsts of South Sulawesi, however, offers new insights. The authors combine use-wear and residue analyses with ethnographic and experimental data to indicate the use of these artefacts as hafted blades within conflict and ritual contexts, revealing hitherto undocumented technological and social practices among Toalean hunter-gatherers. The results suggest these artefacts constitute some of the earliest archaeological evidence for the use of shark teeth in composite weapons.

Figure 1. Map with (inset) the location of Leang Panninge and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1image by K. Newman.

Figure 1. Map with (inset) the location of Leang Panninge and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1image by K. Newman. Figure 2. Archaeological contexts of the perforated shark teeth: a) Leang Panninge cave; b) cave entrance at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1, at the foot of the isolated limestone karst tower; c) stratigraphic profile, Leang Panninge (2019); d–e) stratigraphic profiles, Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 (2018); f) Maros point excavated from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 (Square T9S1) above the Toalean-associated layer that yielded the shark tooth (scale bar is 10mm)Photographs and image compilation by Y. Perston.Langley MC, Duli A, Stephenson B, et al.

Figure 2. Archaeological contexts of the perforated shark teeth: a) Leang Panninge cave; b) cave entrance at Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1, at the foot of the isolated limestone karst tower; c) stratigraphic profile, Leang Panninge (2019); d–e) stratigraphic profiles, Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 (2018); f) Maros point excavated from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 (Square T9S1) above the Toalean-associated layer that yielded the shark tooth (scale bar is 10mm)Photographs and image compilation by Y. Perston.Langley MC, Duli A, Stephenson B, et al.

Shark-tooth artefacts from middle Holocene Sulawesi.

Antiquity. 2023:1-16. doi:10.15184/aqy.2023.144.

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of Antiquity Publications Ltd. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

We know, for instance that the scientists are using the correct decay rates when they use radiometric dating to determine the age of objects like these shark teeth because creationists assure us that if the basic parameters of the Universe were even slightly different, life would be impossible, yet decay rates depend on two of the four fundamental forces - the weak and strong nuclear forces, so, if they were very different 10,000 years ago by an amount that would make 10,000 years look like 3.8 billion, or 14 billion, or whatever is needed to explain the discrepancy between belief and observable reality, then life would have been impossible when it was supposedly created because quite simply, atoms larger than hydrogen would not have existed because their nuclei would have been unstable.

Creationism must be about the only cult that requires its followers to believe that the vast majority of history occurred when there was no place and no time for it to occur in.

But then these are people who can be made to believe that all life on Earth is descended from a tiny number of ancestors that lived in an unventilated box and got out of it onto a sterile planet on which every living substance had been destroyed (Genesis 7:23), including, presumably, the plants the herbivores needed, the insects the insectivores needed and where most of them would have promptly been exterminated by the carnivores.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.