Binocular microscopic images of zircon crystals separated from various studied rocks: (a) gabbro A1: P4, A2: S20; (b) porphyritic granite, B1: S1, B2: L1, B3: S5, B4: S6; (c) fine-grained granite, C1: L3, C2: S12, C3: S7, C4: S12; (d) mylonitic granite, D1: S4, D2: S5, D3: L5, D4: P2; (e) leucocratic granitoid, E1: S3, E2: L5, E3: G1, E4: P2; bars: 100 m.

The Bronze Age creation myths preserved in the Bible assert that Earth is only some 6,000–10,000 years old, depending on how the text is interpreted. The difficulty for those who insist on treating the Bible as literal history is that these claims are casually and repeatedly refuted by real-world evidence. That leaves creationists with few options other than bearing false witness against scientists or asserting that the physical evidence itself must be deceptive—despite their own scripture reassuring them that the god it describes “cannot lie” (Titus 1:2).

The problem is compounded by the fact that scientists are continually improving their ability to measure the age of things, including the histories of entire continents. We can now say, with a high degree of confidence and with abundant supporting evidence, that Earth is billions of years old and has undergone profound changes over that vast span of time. These include the movement of tectonic plates, the rise and erosion of mountain ranges, repeated fluctuations in sea level, major climate shifts, and the appearance, spread, and extinction of forests and entire orders of animal and plant life.

That ability has now taken another significant step forward. A team of scientists from Curtin University in Perth, Australia, and the University of Cologne in Germany has developed a technique that not only allows rocks to be dated, but also reveals what has happened to them over immense spans of time—recorded in microscopic zircon crystals as they were exposed at Earth’s surface, buried, and later re-exposed. Their findings have just been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Three members of the team have also published an open-access article in The Conversation, which I will reproduce below under a Creative Commons licence, formatted for stylistic consistency. Before that, however, here is an explanation of how this remarkable technique works, and why it allows scientists to reconstruct the deep-time history of entire landscapes.

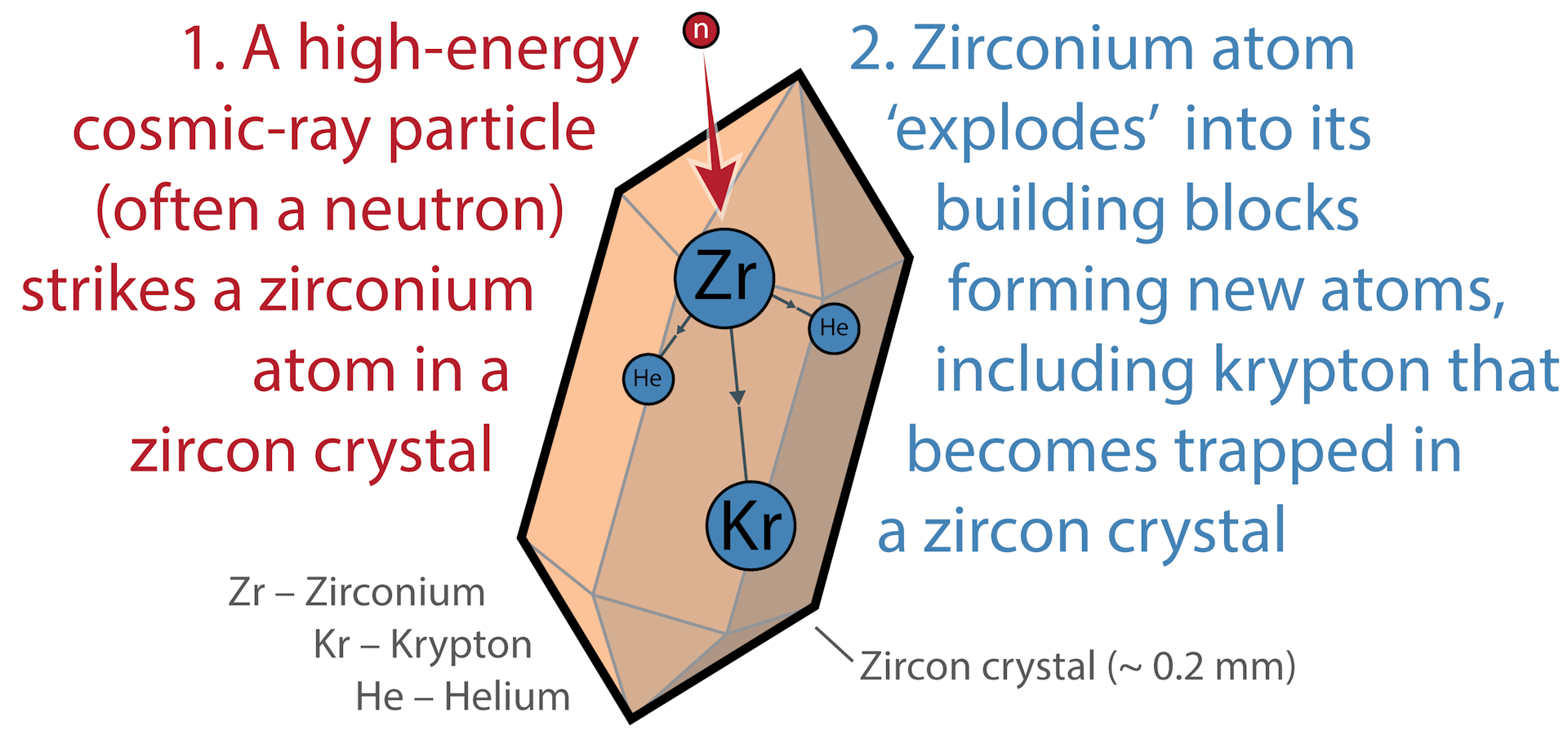

How tiny zircon crystals act as a “cosmic clock”. At first glance, the claim that scientists can reconstruct the rise and fall of ancient Australian landscapes by measuring krypton trapped in microscopic zircon crystals sounds almost mystical. In reality, it is a beautifully simple application of nuclear physics, geology, and a very steady natural clock: cosmic radiation. The key point is this: the method does not date when the rocks formed. Instead, it measures how long parts of the landscape were exposed at or near Earth’s surface. That distinction is crucial.

Why zircon matters

Zircon (ZrSiO₄) is one of geology’s most useful minerals. It is:

- Exceptionally hard and chemically resistant

- Able to survive erosion, transport, burial, and re-exhumation

- Extremely good at retaining noble gases once they are trapped

Most importantly, zircons can already be dated independently using uranium–lead (U–Pb) dating, often showing crystallisation ages of hundreds of millions or even billions of years. That allows scientists to separate when the crystal formed from what happened to it later.

Cosmic rays and krypton: the clock mechanism

High-energy cosmic rays constantly bombard Earth from space. When they strike minerals at or near the surface, they trigger nuclear spallation reactions, knocking particles out of atomic nuclei.

In zircon, these reactions produce rare cosmogenic isotopes of krypton, including:

- ⁸¹Kr

- ⁷⁸Kr

- ⁸⁰Kr

These isotopes are crucial because:

- They are not present when zircon crystallises

- They are produced only when the crystal is within a few metres of the surface

- Once produced, they become locked inside the zircon lattice

When the zircon is buried deeply enough—by sedimentation or tectonic processes—cosmic rays can no longer reach it, and krypton production effectively stops.

What the krypton actually tells us

By measuring how much cosmogenic krypton is present in a zircon grain, and knowing the rate at which cosmic rays produce it, researchers can calculate:

The total amount of time that crystal spent near Earth’s surface.

This is known as an exposure age, not a formation age.

Crucially, this exposure does not have to be continuous. A zircon may have been:

- Exposed at the surface

- Buried

- Re-exposed

- Buried again

The krypton signal records the cumulative surface exposure across all those episodes.

From crystals to continents

So how does this help reconstruct ancient landscapes?

The researchers analysed large numbers of zircons eroded from Australian terrains and compared:

- Their U–Pb crystallisation ages (often very ancient)

- Their cosmogenic krypton exposure ages (much younger)

The striking mismatch between these ages reveals when the rocks were exhumed to the surface, not when they formed.

When many zircons from a region show long cumulative exposure times, it indicates:

- Prolonged surface stability

- Extremely slow erosion

- Long-lived, low-relief landscapes

This is exactly what the study reveals for much of Australia: a continent whose interior has remained remarkably stable for hundreds of millions of years.Why krypton is especially powerfulSchematic illustrations of exhumation mechanisms: ( a ) tectonic extrusion; ( b ) domal uplift

After Maruyama et al. 1996.Schematic illustration of proposed cratonic lithosphere evolution since the Cretaceous. a, Sustained plume activity weakens the intact cratonic lithosphere by warming and metasomatism, forming kimberlites. b, Removal of deep mantle lithosphere including the garnet-peridotite layer and some harzburgite lithosphere. Both the surface and the Moho uplift isostatically, with erosion causing crustal thinning. c, Both internal shear of the lithosphere below the mid-lithosphere discontinuity and growth of a new thermal boundary in regions of delamination record recent mantle deformation with seismic anisotropy. The foundered lithosphere segments stagnate above the lower mantle due to their overall neutral buoyancy. Both high topography and shallow Moho reflect the lower density of the new thermal lithosphere compared to the intact lithosphere.

Other cosmogenic nuclides (such as helium or neon) have been used before, but krypton offers several advantages:

- Multiple isotopes allow internal cross-checks

- Very low diffusion rates in zircon

- Resistance to thermal resetting

- Sensitivity to geological timescales far longer than most surface-dating methods

This makes krypton-in-zircon dating uniquely suited to ancient, tectonically quiet cratons, like Australia.

What this method does not claim.

It is worth being explicit about what this technique is not saying:

- It does not date the formation of rocks

- It does not assume constant exposure

- It does not rely on light exposure or luminescence

Instead, it provides a robust, physics-based measure of how long landscapes remained close to Earth’s surface.

Putting it all together

In short:

- U–Pb dating tells us when a zircon crystal formed deep within Earth

- Cosmogenic krypton tells us when that crystal was exposed at the surface

- Together, they allow geologists to reconstruct the deep-time history of erosion, burial, and landscape stability

It is this combination that underpins the findings discussed in the article from The Conversation and the paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Far from being exotic or speculative, this “cosmic clock” is a precise and independently verifiable tool—one that reveals just how ancient, stable, and dynamic Earth’s landscapes really are.

A ‘cosmic clock’ in tiny crystals has revealed the rise and fall of Australia’s ancient landscapes.

The remnants of violent stellar explosions where cosmic rays are born.

In our new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, we show how this “cosmic clock” uncovers the evolution of rivers, coasts and habitats.

It also shows how giant mineral deposits formed. Products from these deposits end up in everyday ceramic objects – but carry a hidden landscape story.

Looking through deep time

Earth’s surface is constantly changing as the opposing forces of erosion and uplift compete to sculpt the landscape around us – one example of this is mountains rising, then being worn down by weathering.

To understand today’s environments and predict their response to future change, we need to know how landscapes behaved through deep time – millions to billions of years ago.

Until now, directly measuring how ancient landscapes changed has been a big challenge. A new technique finally gives us a window into the distant past of Earth’s surface.

An ancient Australian landscape shaped by millions of years of slow erosion, Kalbarri National Park, Western Australia.

Maximilian Dröllner

By drilling straight down into the subsurface, we recovered samples that reveal ancient beaches fringing the Nullarbor Plain in southern Australia.

Now located more than 100 kilometres from the ocean, these buried shorelines record extraordinary transformations of the landscape. It was once a seabed, later a woodland with giant tree kangaroos and marsupial lions, and today is one of the flattest and driest places on Earth.

These ancient beaches contain unusually high amounts of zircon, a mineral loved by geologists because it is a sturdy time capsule. Inside these tiny crystals, about the width of a human hair, lies a cosmic secret.

Hunting for cosmogenic krypton

Earth is constantly bombarded by cosmic rays – high-energy particles from space produced when stars explode. Unlike larger meteorites that hit our planet, cosmic rays are smaller than atoms. But when they strike atoms within minerals near Earth’s surface, the microscopic “explosions” produce new elements, known as cosmogenic nuclides.

Measuring these nuclides is a popular way to work out how quickly landscapes change. But many nuclides are very short-lived, making them unsuitable for understanding ancient landscapes.

For our measurements, we used cosmogenic krypton stored inside naturally occurring zircon crystals. This technique has only recently become possible thanks to technological advances. It works because krypton does not decay but preserves information for tens or even hundreds of millions of years.

Simplified sketch showing how cosmogenic krypton is produced and trapped inside a zircon crystal.

Maximilian Dröllner

To unlock this “cosmic clock”, we used a laser to vaporise several thousand zircon crystals and measured the krypton released from them. The more krypton a grain contains, the longer it must have been exposed at the surface before getting buried by younger layers of sediment.

A remarkably stable land

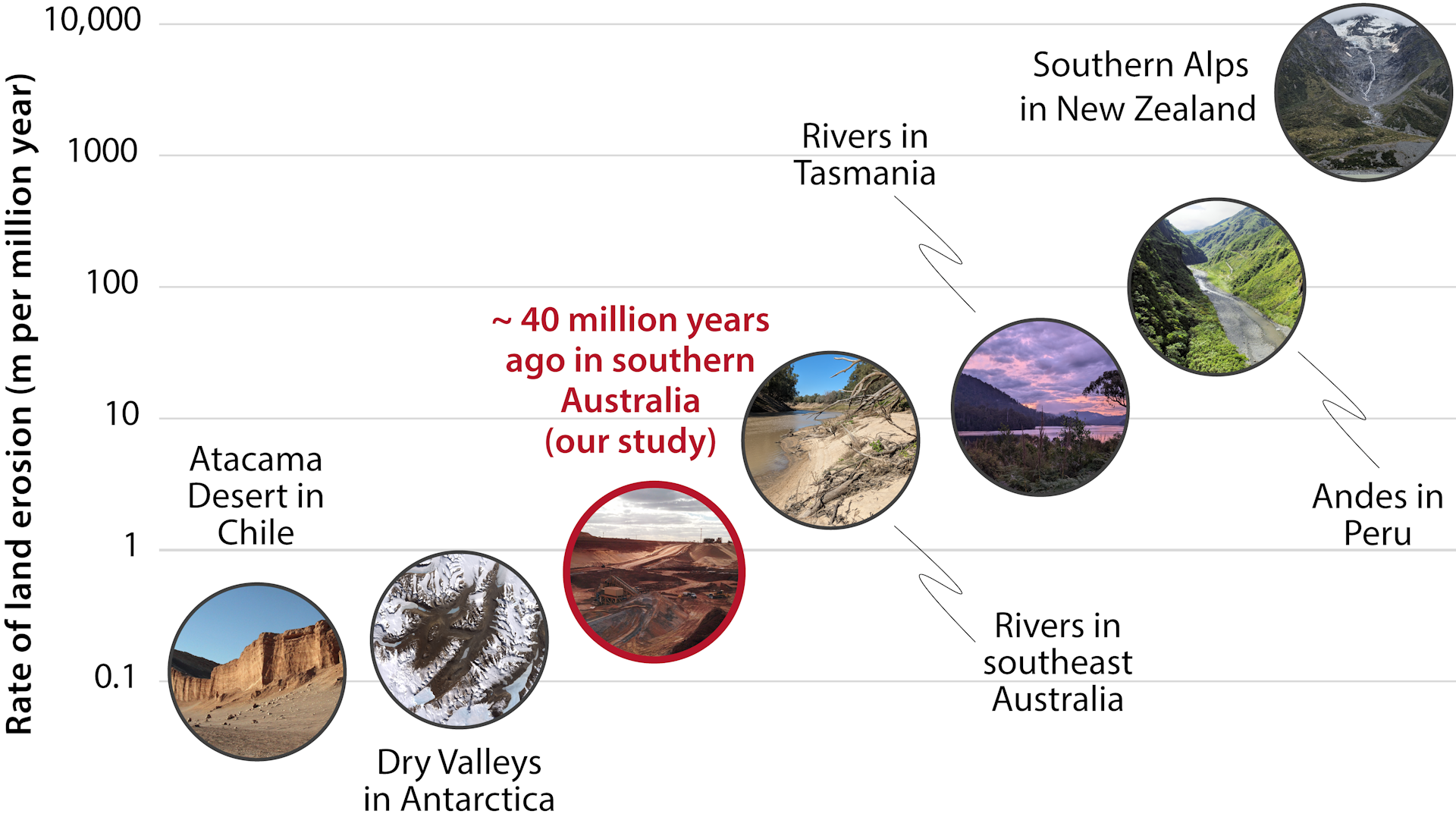

The results show that around 40 million years ago, when Australia was warm, wet and covered by lush forests, landscapes in southern Australia were eroding extremely slowly – less than one metre per million years.

This is far slower than in mountain regions such as the Andes in South America or the Southern Alps in New Zealand. However, this rate of erosion is similar to some of the most stable regions on Earth today, such as the Atacama Desert or the dry valleys of Antarctica.

Comparison of our erosion rate estimates (a key measure of landscape change) with other Australian and global landscapes, highlighting the very slow rates of landscape evolution.

Maximilian Dröllner

Over time, this natural filtering process produced beach sand deposits very rich in economically valuable zircon and other stable minerals.

The results also capture a turning point in the region’s landscape evolution. After a period of relative stability, a shifting climate, Earth movements and sea levels triggered faster erosion. The sediments started to move faster as well.

A new crystal clock

This “cosmic clock” helps explain the mineral wealth along the edges of the Nullarbor Plain, including the world’s largest zircon mine: Jacinth-Ambrosia. This mine produces about a quarter of the global zircon supply.

A lot of zircon is used in ceramics manufacturing, so chances are high many of us have already had contact with these minerals that spent far longer at Earth’s surface than our own species has existed.

By reading cosmic ray fingerprints in zircon, we now have a new geological clock for measuring ancient processes on our planet’s surface.

Investigating modern landscapes, where surface processes can be measured independently, will help refine and broaden its use – but the potential is enormous. Because krypton and zircon are stable, the technique can be applied to periods of Earth history hundreds of millions of years ago.

This opens the possibility of studying landscape responses to some of the biggest events in Earth history, such as the rise of land plants about 500–400 million years ago, which transformed the planet’s surface and atmosphere.

To do this, we could analyse zircon crystals preserved in river sediments from that time, likely allowing us to measure how strongly the arrival of land plants reshaped erosion, sediment transport and landscape stability.

Earth’s landscapes hold memories trapped in minerals formed by cosmic rays. By learning to read this “cosmic clock”, we’ve found a new way to understand the history behind iconic landscapes. Perhaps even more importantly, it provides a blueprint for the changes that may lie ahead.

Maximilian Dröllner, Adjunct Research Fellow, School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University; Georg-August-Universität Göttingen ; Chris Kirkland, Professor of Geochronology, Curtin University, and Milo Barham, Associate Professor, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What makes this work particularly awkward for creationism is not merely the timescales involved—though those alone place it hopelessly beyond any biblical chronology—but the sheer independence and internal consistency of the evidence. The cosmic-ray exposure recorded in zircon crystals is governed by well-understood nuclear physics, calibrated against known cosmic-ray fluxes, and cross-checked using multiple isotopes within the same mineral. It does not depend on assumptions drawn from geology alone, nor on any single dating method that creationists can dismiss with a wave of the hand.

More importantly, this technique reveals something creationist models cannot even begin to accommodate: the history of landscapes. These zircon crystals record long periods of surface exposure punctuated by burial and re-exposure, showing continents evolving slowly over hundreds of millions of years. There is no room here for a young, static Earth hastily assembled a few thousand years ago. Instead, we see a planet shaped by deep time, erosion, tectonics, and climate—processes that leave measurable, cumulative traces in the very fabric of minerals.

As so often happens, creationists will doubtless respond by asserting that the method is “just another assumption,” or by dismissing the results as irrelevant to their beliefs. Yet the same physical principles underpin technologies they rely on daily, from nuclear medicine to satellite navigation. Rejecting them selectively, only when they contradict scripture, is not scepticism—it is special pleading.

Once again, the pattern repeats itself. As scientific techniques improve, the gaps in our understanding shrink, while the gap between creationist claims and reality widens. The Earth is not merely old; it carries a detailed, readable record of its own history, written at atomic scale and legible to anyone prepared to follow the evidence. And as this study shows, that record is becoming ever harder to ignore.

Advertisement

All titles available in paperback, hardcover, ebook for Kindle and audio format.

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.