Long before anatomically modern Homo sapiens took their first tentative steps out of Africa and established themselves in Eurasia, an archaic hominin, Homo erectus, had already done so about a million years earlier, spreading across Asia into what is now the Indonesian archipelago and diversifying into a number of species and regional variants along the way.

One lineage settled on the island of Flores, where they encountered a miniature species of elephant, Stegodon florensis insularis, which probably became one of their principal sources of meat. By a process known to evolutionary biologists as Foster's Rule or the “island effect”, the descendants of these hominins also became smaller, eventually evolving into Homo floresiensis, popularly known as “The Hobbit” on account of their diminutive stature. Then, quite suddenly, they disappeared from history some 50,000 years ago.

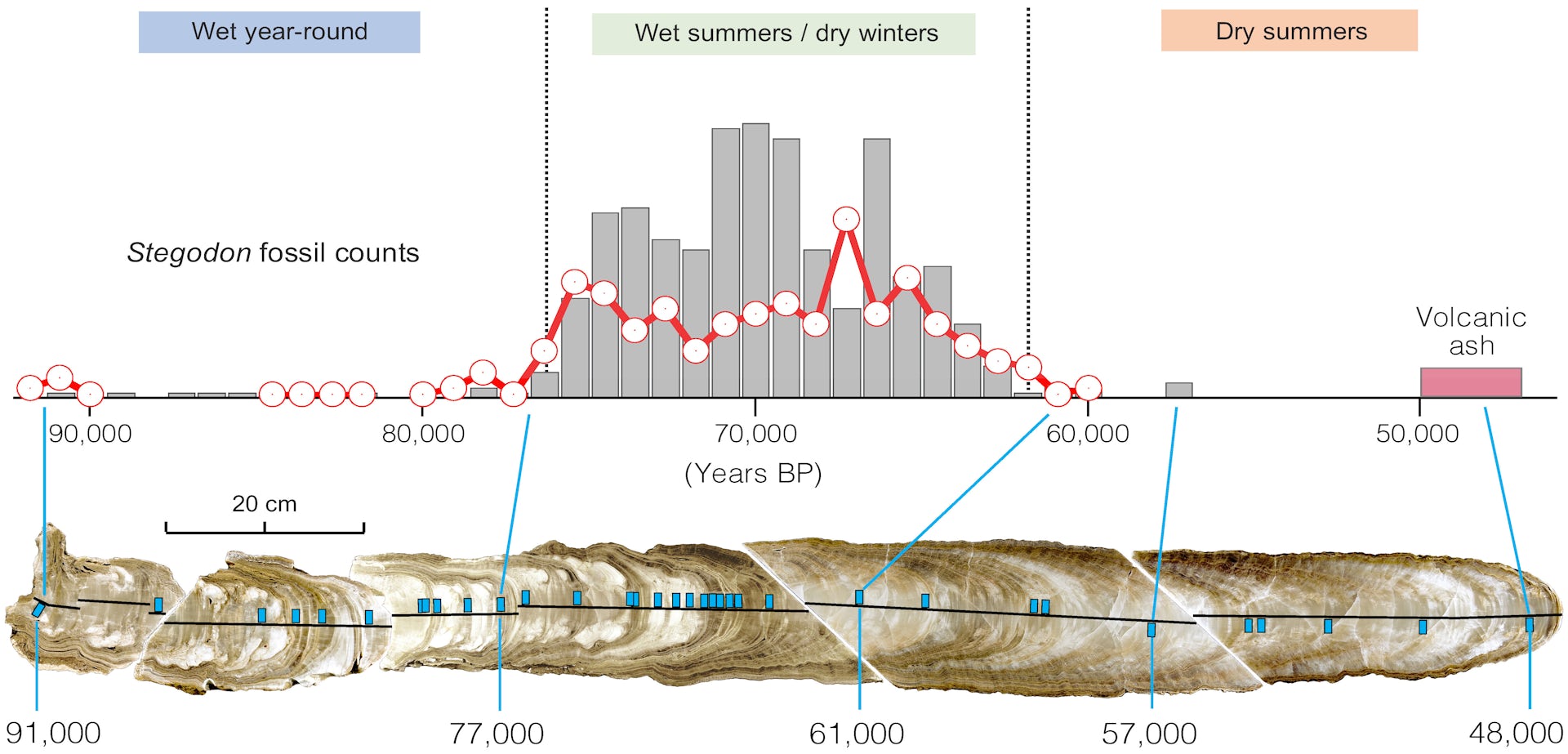

Now an international team of archaeologists, including scientists from the University of Wollongong (UOW), Australia, believe they have found evidence explaining their extinction. It appears to have coincided with the disappearance of Stegodon florensis insularis and to have been driven by extensive climate change that began about 76,000 years ago, culminating in severe summer droughts between 61,000 and 50,000 years ago. The researchers reached this conclusion through analysis of the chemical record preserved in stalagmites from Flores caves, alongside isotopic data from the teeth of Stegodon. Their paper has just been published open access in Communications Earth & Environment.

In addition to the University of Wollongong news release explaining the study, four of the authors have written an article in The Conversation. Their article is reproduced here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency.

The ‘hobbits’ mysteriously disappeared 50,000 years ago. Our new study reveals what happened to their home

Homo floresiensis skull.

Now, new evidence suggests a period of extreme drought starting about 61,000 years ago may have contributed to the hobbits’ disappearance.

Our new study, published today in Communications Earth & Environment, reveals a story of ecological boom and bust. We’ve compiled the most detailed climate record to date for the site where these ancient hominins once lived.

It turns out that H. floresiensis and one of its primary prey, a pygmy elephant, were both forced away from home by a drought lasting thousands of years – and may have come face-to-face with the much larger Homo sapiens.

An island with deep caves

The discovery of H. floresiensis in 2003 changed our thinking on what makes us human. These diminutive small-brained hominins, standing only 1.1 metres tall, made stone tools. Against the odds, they reached Flores seemingly without boat technology.

Bones and stone tools from H. floresiensis were found in Liang Bua cave, hidden away in a small valley in the uplands of the island. These remains date to between 190,000 and 50,000 years ago.

Today, Flores has a monsoonal climate with heavy rainfall during wet summers (mostly from November to March) and lighter rain during drier winters (May to September).

However, during the last glacial period there would have been significant variation in both the amount of rainfall and when it arrived.

To find out what the rains were like, our team turned to a cave 700 metres upstream of Liang Bua named Liang Luar. By pure chance, deep inside the cave was a stalagmite that grew right through the H. floresiensis disappearance interval. As stalagmites grow layer by layer from dripping water, their changing chemical composition also records the history of a changing climate.

Palaeoclimatologists have two main geochemical tools when it comes to reconstructing past rainfall from stalagmites. By looking at a specific measure of oxygen known as d18O, we can see changes in monsoon strength. Meanwhile, the ratio of magnesium to calcium shows us the total rainfall amount.

We paired these measurements for the same samples, precisely anchored them in time, and reconstructed summer, winter and annual rainfall amounts. All this provided unprecedented insight into seasonal climate variability.

We found three key climate phases. It was wetter than today year-round between 91,000 and 76,000 years ago. Between 76,000 and 61,000 years ago, the monsoon was highly seasonal, with wetter summers and drier winters.

Then, between 61,000 and 47,000 years ago, the climate turned much drier in summer, similar to that seen in Southern Queensland today.

The hobbits followed their prey

So we had a well-dated record of major climate change, but what was the ecological response, if any? We needed to build a precise timeline for the fossil evidence of H. floresiensis at Liang Bua.

The solution came unexpectedly from our analysis of d18O in the fossil tooth enamel of Stegodon florensis insularis, a distant extinct pygmy relative of modern elephants.

The jawbone and ridged molar of an adult Stegodon florensis florensis, the large-bodied ancestor of Stegodon florensis insularis. Scale bar is 10 cm.

Gerrit van den Berg

Remarkably, the d18O pattern in the Liang Luar stalagmite and in teeth from increasingly deep sedimentary deposits at Liang Bua aligned perfectly. This allowed us to precisely date the Stegodon fossils and the accompanying remains of H. floresiensis.

The refined timeline showed that about 90% of pygmy elephant remains date to 76,000–61,000 years ago, during the strongly seasonal “Goldilocks” climate. This may have been the ideal environment for the pygmy elephants to graze and for H. floresiensis to hunt them. But both species almost disappeared as the climate got drier.

Cross-section of the precisely dated stalagmite used in this study, showing growth layers. The graph shows the improved timeline for Stegodon fossils in two excavation sectors at Liang Bua.

Mike Gagan

As the climate dried, the primary dry-season water source, the small Wae Racang river, may have dwindled too low, leaving the Stegodon without fresh water. The animals may have migrated out of the area, with H. floresiensis following.

Did a volcano contribute too?

The last few Stegodon fossil remains and stone tools in Liang Bua are covered in a prominent layer of volcanic ash, dated to around 50,000 years ago. We don’t yet know if a nearby volcanic eruption was a “final straw” in the decline of Liang Bua hobbits.

The first archaeological evidence attributed to Homo sapiens is above the ash. So while there is no way of knowing if H. sapiens and H. floresiensis crossed paths, new archaeological and DNA evidence both indicate that H. sapiens were island-hopping across Indonesia to the supercontinent of Sahul by at least 60,000 years ago.

If H. floresiensis were forced by ecological pressures away from their hideaway towards the coast, they may have interacted with modern humans. And if so, could competition, disease, or even predation then have been decisive factors?

Whatever the ultimate cause, our study provides the framework for future studies to examine the extinction of the iconic H. floresiensis in the context of major climate change.

The underlying role of freshwater availability in the demise of one of our human cousins reminds us that humanity’s history is a fragile experiment in survival, and how shifting rainfall patterns can have profound impacts.

Nick Scroxton, Research Fellow, Palaeoclimate, Maynooth University; Gerrit (Gert) van den Bergh, Researcher in Palaeontology, University of Wollongong; Michael Gagan, Honorary Professor, Palaeoclimate, University of Wollongong; The University of Queensland, and Mika Rizki Puspaningrum, Researcher in Palaeontology, Bandung Institute of Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung>

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Whatever the precise balance between climatic stress, ecological fragility and any interaction with incoming modern humans, the emerging picture is one of a small, isolated hominin population living close to environmental limits. When prolonged drought reshaped vegetation patterns and reduced freshwater availability, the consequences would have rippled through the entire ecosystem. The disappearance of *Stegodon florensis insularis* would not merely have removed a prey species; it would have undermined the subsistence base of Homo floresiensis itself.

There is nothing mysterious here in the supernatural sense. Island dwarfism, limited genetic diversity, climatic instability and trophic dependence form a coherent, testable explanation rooted firmly in evolutionary biology and palaeoecology. The same natural processes that produced the Flores hominins ultimately constrained their resilience.

And all of this unfolded tens of thousands of years before the timeline permitted by a literal reading of the Genesis narrative. Long before any proposed Neolithic creation date, before any global flood mythology, a distinct human lineage had already evolved, adapted to island life, and vanished. The evidence from Flores is written not in ancient scripture, but in stone, isotopes and stratigraphy — and it tells a story measured in deep time.

Advertisement

All titles available in paperback, hardcover, ebook for Kindle and audio format.

Prices correct at time of publication. for current prices.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.