Religion, Creationism, evolution, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about.

Thursday, 12 February 2026

Refuting Creationism - Bonobos Can Imagine Things Detached From Reality

Apes share human ability to imagine | Hub

A paper published recently in Science should give creationists something to think about. It shows how our close relatives, the bonobos, can imagine things completely detached from physical reality — rather like children playing games of pretend, or creationists pretending they are leading experts on biology and understand the subject better than the actual experts.

In this study, two researchers from Johns Hopkins University demonstrate that bonobos can engage in imaginative “pretend play”, an ability long assumed to be uniquely human. In doing so, they dismantle yet another supposed human-exclusive trait that creationists cite as evidence of special creation.

In one experiment with a captive bonobo, Kanzi — a 43-year-old individual living at Ape Initiative — a researcher pretended to pour juice from an empty jug into a transparent empty cup, and then pour it again into a second empty cup. When asked, “Where is the juice?”, Kanzi correctly identified the second cup.

In a similar experiment, an imaginary grape was taken from an empty bowl and placed into an empty jar. When asked, “Where is the grape?”, Kanzi again correctly pointed to the jar.

These experiments show that Kanzi was able to imagine and successfully track the movement of invisible, non-existent objects — something human children can typically do by the age of about two.

Saturday, 10 January 2026

Creationism Refuted - Early Hominins From Morocco Confirm The African Origin of Homo Sapiens

Programme Préhistoire de Casablanca

The discovery and dating (of which more later) of hominin remains in a Moroccan quarry, reported recently in Nature, has provided further confirmation that the origin of Homo sapiens lies in Africa, not Eurasia, contrary to an alternative hypothesis that has occasionally been proposed. The material consists of mandibles and other fragmentary remains, and also sheds light on the evolutionary origins of Neanderthals and Denisovans.

That is not to say that any serious palaeoanthropologists believed humans evolved wholly in Eurasia. Rather, some suggested that the final stages of Homo sapiens evolution may have occurred there, derived from descendants of earlier African migrants such as H. erectus, H. rhodesiensis, or H. antecessor. Others have argued that the so-called ‘muddle in the middle’ of the hominin family tree may represent a single, widely distributed species exhibiting regional variation across both Africa and Eurasia.

However, the Moroccan specimens display a clear mosaic of primitive and derived features — precisely the pattern that creationists call ‘transitional species’ and insist don't exist. These fossils combine traits seen in African sister lineages with features associated with H. antecessor, a pre-Neanderthal/Denisovan European species whose remains are being excavated at the Sima de los Huesos (Cave of Bones) site at Atapuerca, Spain.

The fossils are also exceptionally valuable for palaeoanthropology for another reason. The sediments in which they were found preserve the unmistakable signature of the Matuyama–Brunhes geomagnetic reversal, which occurred around 773,000 years ago when Earth’s magnetic poles flipped. This provides an unusually robust chronological anchor, as the timing of this reversal has been independently verified from multiple, entirely separate lines of evidence.

There is therefore a great deal here for creationists to attempt to dismiss. First, there is the mosaic of primitive and derived features that identify these fossils as genuinely transitional — something creationism insists does not exist. Second, there is the age of the material, securely dated to approximately 763,000 years (±4,000 years) before creationists insist Earth was magicked out of nothing, placing ancestral hominins hundreds of thousands of years before the Bronze Age biblical story of a single, ancestor-free human couple. Finally, and perhaps most inconveniently of all, the dating does not rely on radiometric methods at all, but on geomagnetic reversal stratigraphy, verified beyond any reasonable doubt. The biblical timeline is therefore wrong by many orders of magnitude.

Tuesday, 6 January 2026

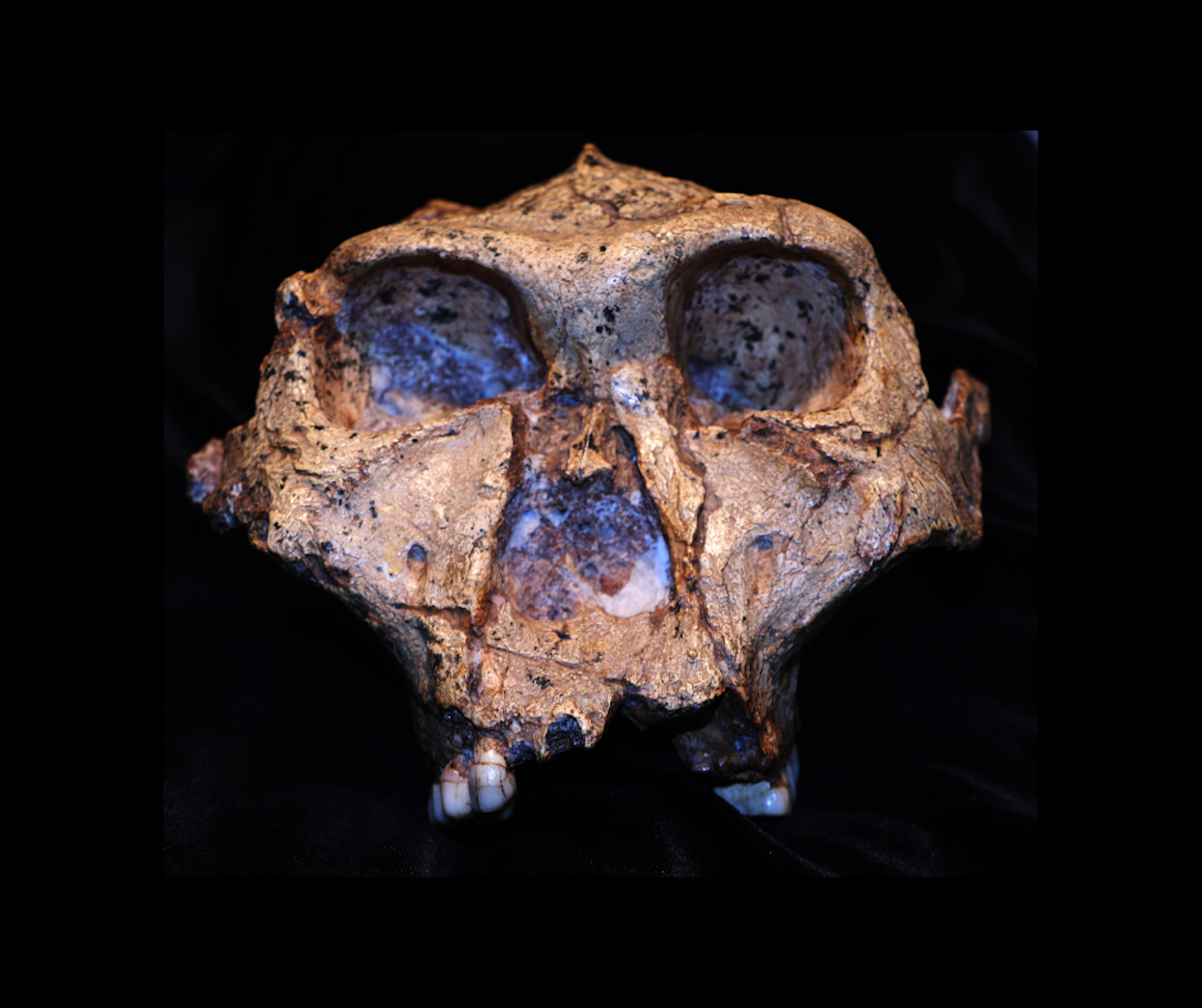

Creationism Refuted - A 'Transitional Species' That is Probably Another Ancestral Hominin

A brief communication, published last November in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology may, if creationists never read past the title (as usual), have produced a frisson of excitement in those circles. It questioned the taxonomic status of one of the most complete fossil skeletons of an early ancestral hominin, Australopithecus prometheus, popularly known as “Little Foot”.

However, reading even a little further would have turned that excitement into disappointment — assuming, of course, that they understood what they were reading. The authors were not questioning whether the fossil was ancestral at all, but whether it had been assigned to the correct position in the hominin family tree, or whether it should instead be recognised as a distinct ancestral hominin species. In other words, this was a discussion about how many transitional species there are, not whether transitional species exist at all.

The only crumb of comfort available to creationists is the familiar claim that this demonstrates how science “keeps changing its mind”, something they take as evidence that science is fundamentally unreliable—presumably including even those parts they routinely misrepresent as supporting their beliefs.

For anyone who understands the scientific method, and the importance of treating all knowledge as provisional and contingent on the best available evidence, this paper represents the principle functioning exactly as it should. Far from being a weakness, this willingness to revise conclusions in the light of new information is what makes science self-correcting and progressively more accurate over time.

The authors of the paper — a team led by La Trobe University adjunct Dr Jesse Martin—carried out a new analysis of the “Little Foot” fossils and concluded that the specimen was probably placed in the wrong taxon when first described on the basis that it does not share the same “unique suite of primitive and derived features” as Australopithecus africanus. Since that initial assessment, additional fossils of A. prometheus have been discovered, and it has become clear that “Little Foot” also differs from those specimens. At the same time, it remains sufficiently distinct from A. africanus that reassignment to that species is not justified. In short, it possesses its own unique combination of primitive and derived traits and should therefore be recognised as a separate species.

Naturally, there is no real comfort here for creationists. The phrase “suite of primitive and derived features” is simply palaeontological shorthand for evidence of descent with modification—what Darwin referred to as transitional forms. It follows that the researchers involved have no doubt whatsoever that the species under discussion evolved from earlier ancestors, and there is no hint that they believe it was spontaneously created, without ancestry, by magic.

Thursday, 18 December 2025

Creationism Refuted - Transitional Evolution of Homo Erectus

Scans provided by National Museum of Ethiopia,

National Museums of Kenya and Georgian National Museum.

Palaeontologists at the College of Graduate Studies, Glendale Campus of Midwestern University in Arizona, have reconstructed the head and face of an early Homo erectus specimen, DAN5, from Gona in the Afar region of Ethiopia on the Horn of Africa. In doing so, they have uncovered several unexpected features that should trouble any creationist who understands their significance. The research has just been published open access in Nature Communications.

Creationism requires its adherents to imagine that there are no intermediate fossils showing a transition from the common Homo/Pan ancestor to modern Homo sapiens, whom they claim were created as a single couple just a few thousand years ago with a flawless genome designed by an omniscient, omnipotent creator. The descendants of such a couple would, of course, show no genetic variation, because both the perfect genome and its replication machinery would operate flawlessly. No gene variants could ever arise.

The reality, however, is very different. Not only are there vast numbers of fossils documenting a continuum from the common Homo/Pan ancestor of around six million years ago, but there is also so much variation among them that it has become increasingly difficult to force them into a simple, linear sequence. Instead, human evolution is beginning to resemble a tangled bush rather than a neat progression.

The newly reconstructed face of the Ethiopian Homo erectus is no exception. It displays a mosaic of more primitive facial traits alongside features characteristic of the H. erectus populations believed to have spread out of Africa in the first of several waves of hominin migration into Eurasia. The most plausible explanation is that the Ethiopian population descended from an earlier expansion within Africa, became isolated in the Afar region, and retained its primitive characteristics while other populations continued to evolve towards the more derived Eurasian form.

The broader picture that has emerged in recent years—particularly since it became clear that H. sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans formed an interbreeding complex that contributed to modern non-African humans—is one of repeated expansion into new environments, evolution in isolation, and subsequent genetic remixing as populations came back into contact. DAN5 represents just one of these populations, which appears to have evolved in isolation for some 300,000 years.

Not only is this timescale utterly incompatible with the idea of the special creation of H. sapiens 6,000–10,000 years ago, but the sheer existence of this degree of variation is also irreconcilable with the notion of a flawless, designed human genome. Even allowing for old-earth creationist claims that a biblical “day” may represent an elastic number of millions of years, the problem remains: a highly variable genome must still be explained as the product of perfect design. A flawless genome created by an omniscient, omnipotent creator should, moreover, have been robust enough to withstand interference following “the Fall” — an event such a creator would necessarily have foreseen, particularly if it also created the conditions for that fall and the other creative agency involved (Isaiah 45:7).

As usual, creationists seem to prefer the conclusion that their supposed intelligent creator was incompetent—either unaware of the future, indifferent to it, or powerless to prevent it—rather than accept the far more parsimonious explanation: that modern Homo sapiens are the product of a long, complex evolutionary history from more primitive beginnings, in which no divine intervention is required.

Origins of Homo erectus Homo erectus appears in the fossil record around 1.9–2.0 million years ago, emerging from earlier African Homo populations, most likely derived from Homo habilis–like ancestors. Many researchers distinguish early African forms as Homo ergaster, reserving H. erectus sensu stricto for later Asian populations, although this is a taxonomic preference rather than a settled fact.The work of the Midwestern University researchers is summarised in a press release published by EurekAlert!

Key features of early H. erectus include:

- A substantial increase in brain size (typically 600–900 cm³ initially, later exceeding 1,000 cm³)

- A long, low cranial vault with pronounced brow ridges

- A modern human–like body plan, with long legs and shorter arms

- Clear association with Acheulean stone tools and likely habitual fire use (by ~1 million years ago)

Crucially, H. erectus was the first hominin to disperse widely beyond Africa, reaching:

- The Caucasus (Dmanisi) by ~1.8 Ma

- Southeast Asia (Java) by ~1.6 Ma

- China (Zhoukoudian) by ~0.8–0.7 Ma

This makes H. erectus not a single, static species, but a long-lived, geographically structured lineage.

Homo erectus as a population complex

Rather than a uniform species, H. erectus is best understood as a metapopulation:

- African populations

- Western Eurasian populations

- East and Southeast Asian populations

These groups experienced repeated range expansions, isolation, local adaptation, and partial gene flow, producing the mosaic anatomy seen in fossils such as DAN5.

This population structure is critical for understanding later human evolution.

Relationship to later Homo species From H. erectus to H. heidelbergensis

By around 700–600 thousand years ago, some H. erectus-derived populations—probably in Africa—had evolved into forms often grouped as Homo heidelbergensis (or H. rhodesiensis for African material).

These hominins had:

- Larger brains (1,100–1,300 cm³)

- Reduced facial prognathism

- Continued Acheulean and early Middle Stone Age technologies

They represent a transitional grade, not a sharp speciation event.

Divergence of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans

Genetic and fossil evidence indicates the following broad pattern:

- ~550–600 ka: A heidelbergensis-like population splits

- African branch → modern Homo sapiens

- Eurasian branch → Neanderthals and Denisovans

Neanderthals

- Evolved primarily in western Eurasia

- Adapted to cold climates

- Distinctive cranial morphology

- Contributed ~1–2% of DNA to all non-African modern humans

Denisovans

- Known mostly from genetic data, with sparse fossils (Denisova Cave)

- Closely related to Neanderthals but genetically distinct

- Contributed genes to Melanesians, Aboriginal Australians, and parts of East and Southeast Asia, including variants affecting altitude adaptation (e.g. EPAS1)

Modern Homo sapiens

- Emerged in Africa by ~300 ka

- Retained genetic continuity with earlier African populations

- Dispersed out of Africa multiple times, beginning ~70–60 ka

- Interbred repeatedly with Neanderthals and Denisovans

The key point: no clean branching tree

Human evolution is reticulate, not linear:

- Species boundaries were porous

- Gene flow occurred repeatedly

- Populations diverged, adapted, re-merged, and diverged again

Homo erectus is not a side branch that “went extinct”, but a foundational grade from which multiple later lineages emerged. DAN5 fits neatly into this framework: a locally isolated erectus population retaining ancestral traits while others continued evolving elsewhere.

Why this matters

This picture:

- Explains mosaic anatomy in fossils

- Accounts for genetic admixture in living humans

- Makes sense of long timescales and geographic diversity

- Is incompatible with any model of recent, perfect, single-pair creation

Instead, it shows that our species is the outcome of millions of years of population dynamics, not a single moment of design.

A new fossil face sheds light on early migrations of ancient human ancestor

A New Fossil Face Sheds Light on Early Migrations of Ancient Human Ancestor

A 1.5-million-year-old fossil from Gona, Ethiopia reveals new details about the first hominin species to disperse from Africa. Summary: Virtual reassembly of teeth and fossil bone fragments reveals a beautifully preserved face of a 1.5-million-year-old human ancestor—the first complete Early Pleistocene hominin cranium from the Horn of Africa. This fossil, from Gona, Ethiopia, hints at a surprisingly archaic face in the earliest human ancestors to migrate out of Africa.

A team of international scientists, led by Dr. Karen Baab, a paleoanthropologist at the College of Graduate Studies, Glendale Campus of Midwestern University in Arizona, produced a virtual reconstruction of the face of early Homo erectus. The 1.5 to 1.6 million-year-old fossil, called DAN5, was found at the site of Gona, in the Afar region of Ethiopia. This surprisingly archaic face yields new insights into the first species to spread across Africa and Eurasia. The team’s findings are being published in Nature Communications.

We already knew that the DAN5 fossil had a small brain, but this new reconstruction shows that the face is also more primitive than classic African Homo erectus of the same antiquity. One explanation is that the Gona population retained the anatomy of the population that originally migrated out of Africa approximately 300,000 years earlier.

Dr. Karen L. Baab, lead author

Department of Anatomy

Midwestern University

Glendale, AZ, USA.

Gona, Ethiopia

The Gona Paleoanthropological Research Project in the Afar of Ethiopia is co-directed by Dr. Sileshi Semaw (Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana, Spain) and Dr. Michael Rogers (Southern Connecticut State University). Gona has yielded hominin fossils that are older than 6.3 million years ago, and stone tools spanning the last 2.6 million years of human evolution. The newly presented hominin reconstruction includes a fossil brain case (previously described in 2020) and smaller fragments of the face belonging to a single individual called DAN5 dated to between 1.6 and 1.5 million years ago. The face fragments (and teeth) have now been reassembled using virtual techniques to generate the most complete skull of a fossil human from the Horn of Africa in this time period. The DAN5 fossil is assigned to Homo erectus, a long-lived species found throughout Africa, Asia, and Europe after approximately 1.8 million years ago.

How did the scientists reconstruct the DAN5 fossil?

The researchers used high-resolution micro-CT scans of the four major fragments of the face, which were recovered during the 2000 fieldwork at Gona. 3D models of the fragments were generated from the CT scans. The face fragments were then re-pieced together on a computer screen, and the teeth were fit into the upper jaw where possible. The final step was “attaching” the face to the braincase to produce a mostly complete cranium. This reconstruction took about a year and went through several iterations before arriving at the final version.

Dr. Baab, who was responsible for the reconstruction, described this as “a very complicated 3D puzzle, and one where you do not know the exact outcome in advance. Fortunately, we do know how faces fit together in general, so we were not starting from scratch.”

What did scientists conclude?

This new study shows that the Gona population 1.5 million years ago had a mix of typical Homo erectus characters concentrated in its braincase, but more ancestral features of the face and teeth normally only seen in earlier species. For example, the bridge of the nose is quite flat, and the molars are large. Scientists determined this by comparing the size and shape of the DAN5 face and teeth with other fossils of the same geological age, as well as older and younger ones. A similar combination of traits was documented previously in Eurasia, but this is the first fossil to show this combination of traits inside Africa, challenging the idea that Homo erectus evolved outside of the continent.

I'll never forget the shock I felt when Dr. Baab first showed me the reconstructed face and jaw. The oldest fossils belonging to Homo erectus are from Africa, and the new fossil reconstruction shows that transitional fossils also existed there, so it makes sense that this species emerged on the African continent,” says Dr. Baab. “But the DAN5 fossil postdates the initial exit from Africa, so other interpretations are possible.

Dr. Yousuke Kaifu, co-author

The University Museum

The University of Tokyo

Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japa.

This newly reconstructed cranium further emphasizes the anatomical diversity seen in early members of our genus, which is only likely to increase with future discoveries.

Dr. Michael J. Rogers, co-author.

Department of Anthropology

Southern Connecticut State University

New Haven, CT, USA.

It is remarkable that the DAN5 Homo erectus was making both simple Oldowan stone tools and early Acheulian handaxes, among the earliest evidence for the two stone tool traditions to be found directly associated with a hominin fossil.

Dr. Sileshi Semaw, co-author

Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH)

Burgos, Spain.

Future Research

The researchers are hoping to compare this fossil to the earliest human fossils from Europe, including fossils assigned to Homo erectus but also a distinct species, Homo antecessor, both dated to approximately one million years ago.

Comparing DAN5 to these fossils will not only deepen our understanding of facial variability within Homo erectus but also shed light on how the species adapted and evolved.

Dr. Sarah E. Freidline, co-author

Department of Anthropology

University of Central Florida

Orlando, FL, USA.

There is also potential to test alternative evolutionary scenarios, such as genetic admixture between two species, as seen in later human evolution among Neanderthals, modern humans and “Denisovans.” For example, maybe DAN5 represents the result of admixture between classic African Homo erectus and the earlier Homo habilis species.

We’re going to need several more fossils dated between one to two million years ago to sort this out.

Dr. Michael J. Rogers.

Publication:

Abstract

The African Early Pleistocene is a time of evolutionary change and techno-behavioral innovation in human prehistory that sees the advent of our own genus, Homo, from earlier australopithecine ancestors by 2.8-2.3 million years ago. This was followed by the origin and dispersal of Homo erectus sensu lato across Africa and Eurasia between ~ 2.0 and 1.1 Ma and the emergence of both large-brained (e.g., Bodo, Kabwe) and small-brained (e.g., H. naledi) lineages in the Middle Pleistocene of Africa. Here we present a newly reconstructed face of the DAN5/P1 cranium from Gona, Ethiopia (1.6-1.5 Ma) that, in conjunction with the cranial vault, is a mostly complete Early Pleistocene Homo cranium from the Horn of Africa. Morphometric analyses demonstrate a combination of H. erectus-like cranial traits and basal Homo-like facial and dental features combined with a small brain size in DAN5/P1. The presence of such a morphological mosaic contemporaneous with or postdating the emergence of the indisputable H. erectus craniodental complex around 1.6 Ma implies an intricate evolutionary transition from early Homo to H. erectus. This finding also supports a long persistence of small-brained, plesiomorphic Homo group(s) alongside other Homo groups that experienced continued encephalization through the Early to Middle Pleistocene of Africa.

Introduction

The oldest fossils assigned to our genus are ~2.8 million years old (Myr) from Ethiopia and signal a long history of Homo evolution in the Rift Valley1,2,3. There is evidence of multiple Homo lineages in Africa by 2.0–1.9 million years ago (Ma) and an archaeological and paleontological record of expansion to more temperate habitats in the Caucasus and Asia between 2.0 and 1.8 Ma4 (Fig. 1). The last appearance datum for the more archaicHomo habilis species (or “1813 group”) is ~1.67 (OH 13) or ~1.44 Ma, if KNM-ER 42703 is correctly attributed to H. habilis5, which is uncertain6. The archetypal early African Homo erectus fossils from Kenya (i.e., KNM-ER 3733, 3883; and the adolescent KNM-WT 15000) already present a suite of traits that distinguish them from early Homo taxa by 1.6–1.5 Ma, including larger brains and bodies, smaller postcanine dentition, more pronounced cranial superstructures (e.g., projecting and tall brow ridges), a relatively wide midface and nasal aperture, deep palate, and projecting nasal bridge1,6,7,8,9,10,11. The only evidence for H. erectus sensu lato in Africa before 1.8 Ma are fragmentary or juvenile fossils12,13,14, while fossils expressing both ancestral H. habilis and more derived H. erectus s.l. morphological traits are only known from Dmanisi, Georgia at 1.77 Ma15,16. Thus, H. erectus emerged from basal Homo between 2.0 and 1.6 million years ago, but when, where (Africa or Eurasia), and how it occurred remain unclear. An expanded fossil record also documents significant variation in endocranial 17,18 and craniofacial6,8 and dentognathic morphology19,20 throughout the Early Pleistocene, which extends to the Middle Pleistocene with the addition of small-brained Homo lineages to the human tree.The initial announcement of DAN5/P1 assigned it to H. erectus on the basis of derived neurocranial traits21. Subsequent analyses of neurocranial shape and endocranial morphology confirmed affinity with H. erectus but also noted similarities to early (pre-erectus) Homo fossils such as KNM-ER 181317,18. Only limited information about the partial maxilla and dentition was presented in the original description21. Yet, facial and dental traits are increasingly important in early Homo systematics, given overlap in brain size among closely related hominins6,8,22. The DAN5/P1 fossil is a rare opportunity to evaluate neurocranial, facial, and dental anatomy in a single Early Pleistocene Homo fossil and thus has significant implications for this discussion.Fig. 1: Early Homo and Homo erectus timeline between 2.0 and 1.0 Ma and map of key sites in Africa and southern Eurasia. The solid bars of the timeline indicate well-established first and last appearance data; the horizontal stripes indicate possible extensions of the time range based on fragmentary or juvenile fossils. Diagonal lines signal earlier archaeological presence in those regions. The question mark indicates a possible date of <1.49 Ma for the Mojokerto, Indonesia site cf.22,23,24,25. The horizontal gray bar represents the time range associated with DAN5/P1. Colors on the map indicate presence of fossils matching taxa or geographic groups of H. erectus as indicated in the timeline. Surface renderings of the best-preserved regional representatives of archaic or small-brained Homo fossils (beginning at top and continuing clockwise): D2700, KNM-ER 1813, KNM-ER 1470, KNM-ER 3733, SK 847, OH 24, KNM-WT 15000, and DAN5/P1. All surface renderings visualized at FOV 0° (parallel). Map was generated in “rnaturalearth” package68 for R.

The solid bars of the timeline indicate well-established first and last appearance data; the horizontal stripes indicate possible extensions of the time range based on fragmentary or juvenile fossils. Diagonal lines signal earlier archaeological presence in those regions. The question mark indicates a possible date of <1.49 Ma for the Mojokerto, Indonesia site cf.22,23,24,25. The horizontal gray bar represents the time range associated with DAN5/P1. Colors on the map indicate presence of fossils matching taxa or geographic groups of H. erectus as indicated in the timeline. Surface renderings of the best-preserved regional representatives of archaic or small-brained Homo fossils (beginning at top and continuing clockwise): D2700, KNM-ER 1813, KNM-ER 1470, KNM-ER 3733, SK 847, OH 24, KNM-WT 15000, and DAN5/P1. All surface renderings visualized at FOV 0° (parallel). Map was generated in “rnaturalearth” package68 for R.

Here we present a new cranial reconstruction of the 1.6–1.5 Myr DAN5/P1 fossil from Gona, Ethiopia. This study demonstrates that the small-brained adult DAN5/P1 fossil (598 cm3 21) presents a previously undocumented combination of early Homo and H. erectus features in an African fossil.

Baab, K.L., Kaifu, Y., Freidline, S.E. et al.

New reconstruction of DAN5 cranium (Gona, Ethiopia) supports complex emergence of Homo erectus.

Nat Commun 16, 10878 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66381-9

Copyright: © 2025 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Taken together, the evidence leaves little room for the idea that Homo erectus was a dead-end curiosity, neatly replaced by something entirely new. Instead, it represents a long-lived, widely dispersed, and internally diverse population complex that provided the evolutionary substrate from which later human lineages emerged. Its descendants were not produced by sudden leaps or special creation events, but by the ordinary, observable processes of population divergence, isolation, and adaptation acting over deep time.

Modern Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans did not arise as separate “kinds”, nor did they follow clean, branching paths. They represent regional outcomes of this erectus-derived heritage, shaped by geography, climate, and repeated episodes of contact and interbreeding. The genetic legacy of those interactions is still present in living humans today, providing independent confirmation of what the fossil record has long been indicating.

What emerges is not a ladder of progress but a dynamic, reticulated history: populations spreading, fragmenting, evolving in isolation, and reconnecting again. Fossils such as DAN5 are not anomalies to be explained away; they are exactly what we should expect from evolution operating on structured populations across continents and hundreds of thousands of years.

For creationism, this is deeply inconvenient. For evolutionary biology, it is precisely the kind of rich, internally consistent picture that arises when multiple independent lines of evidence converge on the same conclusion: humanity is the product of a long, complex evolutionary history, not a recent act of design.

Thursday, 30 October 2025

Refuting Creationism - The Human Skull Evolved Fastest of All the Apes

Humans evolved fastest amongst the apes | UCL News - UCL – University College London

A newly published paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society B by researchers from University College London (UCL) shows that the human skull evolved relatively rapidly compared to that of other apes. The evolutionary changes involve modifications in the size and shape of the facial and cranial bones.

This serves as a reminder of just how artificial and functionally useless the creationist concept of a “kind” is. It should also show creationists the fallacy of the frequent claim that biologists are abandoning the Theory of Evolution, since this paper discusses the results of evolution, not some infantile notion of magical intervention by an unevidenced supernatural entity.

Creationists are quite content to regard all cats—from domestic tabbies to tigers—as belonging to the same “kind”, even though the main difference between them lies in the size of their skeletons. Yet they balk at the idea that humans and the great apes could belong to the same “kind”, despite the fact that the key distinctions between us and them are also differences in size and proportion—most notably in the bones of the skull.

But then, “kind” is precisely the sort of term creationists favour because it has no fixed definition and can be expanded or contracted to suit whatever argument they are trying to make. The only consistent rule seems to be that whatever constitutes a “kind”, it must always exclude humans. This sometimes leads to the absurdity of defining an “animal kind” and a separate “human kind”.

The UCL team suggest that the rapid evolution of the human skull can be explained by the considerable advantage conferred by a larger brain and advanced cognitive abilities.

Our complex cognition allows us to communicate abstract ideas through both words and gestures—what we call “body language”—much of which depends on facial expression. A flat, forward-facing face enhances our ability to convey and interpret these subtle cues. As social animals, we identify acquaintances and strangers by their faces; we watch the faces of those who speak to us; and we instinctively read emotions such as pleasure, anger, confusion, or distress in their expressions.

In short, it is our large brain and expressive face that make us human — not the addition of new organs or limbs, as creationists often insist marks a change above the genus level, but rather differences in the size and shape of the bones of the skull. Given the close similarity of our genomes to those of other apes, these differences arise not from the amount of genetic information, but from the way that information is regulated during embryonic development.

Thursday, 9 October 2025

Refuting Creationism - Hominins Hunted Elephants in Italy - 400,000 Years Before 'Creation Week'

Early humans butchered elephants using small tools and made big tools from their bones | EurekAlert!

A recent archaeological finding, by Beniamino Mecozzi of Sapienza University of Rome, Italy and colleagues, at the site of Casal Lumbroso in northwest Rome, has once again refuted the Bible narrative by extending the known depth of human prehistory far beyond the limits imposed by biblical literalism.

In sediments dated to some 400,000 years before creationism’s mythical 'Creation Week', the research team has uncovered evidence that early humans were butchering elephants with small stone tools and then fashioning large implements from the animals’ bones. These traces of planning, adaptation, and technological innovation demonstrate that human ingenuity was already well advanced hundreds of millennia before the supposed creation of Adam.

More interestingly from a scientific perspective is not the incidental refutation of ancient creation myths, which happens with almost every archaeological and palaeontological discovery, but the fact that these hominins predate the successful Homo sapiens migration out of African and into Eurasia by tens of thousands of years and pre-date even the earliest evidence of Neanderthals in western Eurasia. Such discoveries highlight the sheer scale of time over which our lineage evolved—an evolutionary saga measured not in millennia but in hundreds of thousands of years. The people who left these marks were not modern humans, but archaic members of the genus Homo, close relatives or ancestors of the Neanderthals. Their world was already ancient when the earliest chapters of Genesis were imagined.

Saturday, 30 August 2025

Abiogenesis News - UCL Scientists Show How LUCA Arose - No God(s) Required

Chemists recreate how RNA might have reproduced for first time | UCL News - UCL – University College London

The day creationists dread — the final closure of their favourite god-shaped abiogenesis gap — moved a little closer last May, when scientists at University College London (UCL) announced that they had shown how the first RNA could have reproduced. In a selective environment with competition for resources, this would have led inevitably to ever-increasing efficiency in replication, kick-starting the whole evolutionary process and the emergence of self-organising systems (or “life”) from prebiotic precursors (or “non-life”). This is, of course, the very process that creationists insist is “impossible”, clinging to the idea that “life” is some magical essence that must be granted by a supernatural deity.

When this God-shaped gap is finally and conclusively closed — as all the others have been — creationists will need to scramble once again to reframe their beliefs and cling to whatever shrinking space remains for their god. Just as their old claim that evolution was “impossible” collapsed, to be replaced with notions of a short burst of warp-speed evolution “within kinds” after “The Flood” (and supposedly still happening today, but conveniently “guided” by God), so too will abiogenesis inevitably be rebranded as yet another process directed by divine intention — naturally, with the eventual production of (American) humans as the goal.

Sunday, 24 August 2025

Refuting Creationism - A Denisovan Gene Helped Humans Populate The Americas

The Denisovan-like haplotype (in orange) was first introgressed from Denisovans into Neanderthals and then introgressed into modern humans. The introgressed haplotype later experienced positive selection in populations from the Americas. The introgressed MUC19 haplotype is composed of a 742-kb region that contains Neanderthal-specific variants (blue). Embedded within this Neanderthal-like region is a 72-kb region containing a high density of Denisovan-specific variants (orange), and an exonic variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) region (gray). The box below the 742-kb region depicts zooming into the MUC19 VNTR region, in which admixed American individuals carry an elevated number of tandem repeat copies.

Another day; another scientific paper showing the Bible to be wrong — not just slightly wrong, but fundamentally, demonstrably, and irretrievably wrong.

This latest blow comes from researchers at Brown University, who have traced a variant of the gene MUC19, originally identified in the extinct archaic hominins known as Denisovans, and found it alive and well today in modern Latin Americans with Indigenous ancestry. They also detected it in ancient DNA recovered from archaeological sites across both North and South America.

The variant is far too common in modern populations to be a trivial accident. Its persistence screams survival advantage. Natural selection has kept it in play because it helps its carriers thrive in the environments the earliest migrants into the Americas encountered.

What does MUC19 do? It helps build mucus — not glamorous, but life-saving. From the saliva that begins digestion to the mucosal barriers in the gut and respiratory tract that fend off infection, this gene equips its owners with a stronger shield against disease.

And where did it come from? The Denisovans. But it likely reached us by way of Neanderthals, with whom Homo sapiens also interbred. In other words, modern humans are not some isolated “special creation” freshly minted out of clay a few thousand years ago; we are a patchwork of lineages, woven together by repeated episodes of interbreeding over tens of thousands of years.

For creationists, this paper is a nightmare. First, the scientists are explicit: the explanation rests entirely on Evolution and the blind, natural processes that drive it. Second, the mere fact that extinct species like Denisovans and Neanderthals could successfully mate with our ancestors drives a stake through the heart of biblical literalism. Instead of Adam and Eve, what we see is gradual emergence — modern humans arising by incomplete speciation across a broad geographical spread, with genes flowing back and forth whenever populations met again. This pattern repeats itself throughout hominin history, and it unfolds on a timeline that makes the biblical six-thousand-year fantasy look laughably naïve.

Saturday, 16 August 2025

Refuting Creationism - A Tiny Piece of DNA That's So Unkind To Creationists

A Genetic Twist that Sets Humans Apart

Humans and chimpanzees share about 98–99% of their DNA, so the vast differences between us must lie within that small fraction where we differ.

Humans have no organs or structures that chimpanzees don’t also have; the differences are mainly in relative size and proportion. In other words, they’re quantitative, not qualitative. But that doesn’t stop creationists solemnly declaring that we are a totally different “kind” — a human “kind” — while chimps are lumped with gorillas, bonobos, and orangutans into the “ape kind.” Two bins, job done.

Creationists insist that no “kind” could have evolved from another because that would require brand-new organs and “new genetic information,” something they claim is impossible. Instead, they set up a straw man, accusing scientists of believing new genes and structures simply pop into existence out of thin air, like some sort of Darwinian magic trick, while insisting no one can explain how it works. (Apparently, gene duplication, mutation, and selection don’t count when you’ve decided in advance that the answer must be wrong.)

But when it comes to humans and chimpanzees, their reasoning ties itself in knots. Humans can’t have evolved from a chimp-like ancestor, they say, because that would be “macro-evolution.” Except when it isn’t. Lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs, and house cats are all just one happy “cat kind,” because in that case there was obviously no “macro-evolution” — only “variation.” So, if evolution produces cats, that’s “micro-evolution.” If it produces humans, it’s “macro-evolution,” and therefore impossible. Heads I win, tails you lose.

In reality, the major differences between humans and chimpanzees aren’t about inventing new bits and pieces, but in how the same components developed. The key lies in relative sizes of bones, muscles, and teeth — and above all in the brain: not new parts, but differences in growth, proportion, and how the brain is wired.

Now, researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine have shown that part of that small genetic difference — specifically a stretch of DNA called HAR123 — acts as an enhancer controlling brain growth and development. In other words, the real evolutionary leap wasn’t the conjuring up of brand-new organs from nowhere, but changes in how existing genes fine-tuned brain development. The decisive shift came not from what parts the brain has, but from how large they grew and the ratio of cell types — glial cells and neurons — within them.

Friday, 15 August 2025

Refuting Creationism - How Denisovans Created Modern Non-African Humans

There is increasing evidence that the human evolutionary story is far richer and more complex than was once assumed, back when many expected a neat series of fossils showing a linear descent from a single African ancestor.

It is also becoming increasingly clear that the Bronze Age human-origin myth in the Bible has about as much historical credibility as Enid Blyton’s Noddy’s Adventures in Toyland — and at least Blyton never claimed her stories were literal truth or the basis of moral authority. Unlike creation myths, Noddy’s adventures were always meant for the nursery, not the classroom.

We now understand that hominin populations frequently split into regional varieties which diversified as more or less isolated groups, only to merge again later into a single population. This process appears to have begun even as we were diverging from the common ancestor we share with chimpanzees. For around a million years after that split, interbreeding remained possible, with chimpanzee genes entering the hominin genome and vice versa.

The interbreeding that most shaped modern, non-African Homo sapiens occurred when African H. sapiens encountered Neanderthals—or their immediate ancestors—during successive waves of migration, permitted by changes in climate and geography. These contacts culminated in the last and only successful migration between roughly 60,000 and 40,000 years ago.

The Neanderthals themselves were descended from an earlier migration that had followed H. erectus into Eurasia, later splitting into Neanderthals in western Eurasia and Denisovans in eastern and south-eastern Eurasia. Modern genomics now shows that it was the Denisovans who contributed even more to the ancestry of non-African H. sapiens than the Neanderthals did. The Denisovans—likely to be reclassified as H. longi, the name given to a skull found in China—appear to have diversified into populations adapted to environments as varied as the Tibetan Plateau and the subtropical coasts of Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Austronesia.

Saturday, 2 August 2025

Creationism Refuted - Common Origins of Alcohol Metabolism In Humans And African Apes

Scrumped fruit key to chimpanzee life and a major force of human evolution | University of St Andrews news

The human ability to consume and metabolise alcohol efficiently may trace back to our ape ancestors, who regularly ate overripe and fermented fruit with a naturally high alcohol content. This is according to researchers from the University of St Andrews, Scotland, and Dartmouth College, USA.

The bad news for creationists is that this discovery strongly supports the common ancestry of modern apes and humans. The researchers are in no doubt that the Theory of Evolution explains the presence of the same genetic mutation in African apes — including humans — which allows us to metabolise alcohol around 40 times more efficiently than orangutans, which lack the mutation.

This mutation enables African apes to consume fermented fruit — often as a social activity — in a pattern of alcohol consumption strikingly similar to that seen in humans.

To describe this behaviour in wild chimpanzees, the researchers have borrowed the term scrumping — a familiar UK English word for the (often illicit) picking and eating of apples, particularly by children. The word derives from the Middle Low German schrimpen, meaning ‘shrivelled or shrunken’ (to describe over-ripe fruit). It also survives in the name of the traditional West Country cider known as scrumpy.

Friday, 1 August 2025

Refuting Creationism - A Diverse Human Population in China - 290,000 Years Before 'Creation Week'

A study reveals the human diversity in China during Middle Pleistocene | CENIEH

A study recently published in the Journal of Human Evolution reports the discovery of a mixture of archaic and modern traits in the dentition of 300,000-year-old hominin fossils unearthed at the Hualongdong site in Anhui Province, China.

These fossils predate the migration of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) out of Africa by around 250,000 years. They indicate that hominin populations in East Asia were already diversifying and possibly interbreeding with archaic humans, such as Homo erectus, to form lineages distinct from both Neanderthals and Denisovans.

The research, led by Professor Wu Xiujie, director of the Hualongdong excavations, is the result of a longstanding collaboration between scientists from the Dental Anthropology Group at CENIEH — María Martinón-Torres, Director of CENIEH and corresponding author of the paper, and José María Bermúdez de Castro, researcher ad honorem at CENIEH — and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing.

The findings reveal a rich and complex picture of human evolution in East Asia, wholly at odds with the simplistic biblical narrative still clung to by creationists. That account, written by ancient people with no knowledge of the broader world, reflects a worldview in which Earth was small, flat, covered by a dome, and located at the centre of the universe.

Sunday, 13 July 2025

Creationism Refuted - There May Have Been Two Or More Species Of the Hominin Paranthropus That Interbred

Where exactly the archaic hominin, Paranthropus robustus fits into the human evolutionary tree remains a subject of debate among palaeontologists. This species lived in southern Africa around 2 million years ago. They walked upright, indicating a shared ancestry with the Australopithecus and the later Homo genus. However, their comparatively small brains and massive jaws and teeth suggest a distinct evolutionary path, likely adapted for processing tough, fibrous plant material.

Determining their precise place in our evolutionary history would ideally require DNA analysis—but DNA does not survive long in the warm African climate. To overcome this limitation, a team of African and European researchers from the fields of molecular science, chemistry, and palaeoanthropology turned to a cutting-edge technique known as palaeoproteomics. By analysing proteins recovered from ancient tooth enamel, they were able to infer aspects of the underlying DNA, since the amino acid sequence in proteins is directly determined by the nucleotide sequence in DNA.

Their findings suggest that the story of early hominins is more complex than previously thought. There may have been more than one closely related species, with evidence of interbreeding or genetic divergence followed by remixing — patterns that would later come to characterise the tangled branches of the hominin family tree.

The research team included three postdoctoral scientists from the University of Copenhagen — Palesa P. Madupe, Claire Koenig, and Ioannis Patramanis — who have written about their work and its significance in the open-access magazine The Conversation.

Their findings are also published in Science.

Their article in The Conversation is reproduced here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Tuesday, 22 April 2025

Refutiing Creationism - How Environmental Variability in Africa Produced Co-operative, Intelligent Humans

This article is best read on a laptop, desktop, or tablet

Environmental Variability Promotes the Evolution of Cooperation Among Humans: A Simulation-Based Analysis | Research News - University of Tsukuba

In a compelling example of how environmental change can drive evolutionary development, two researchers, Masaaki Inaba and Eizo Akiyama, of the University of Tsukuba, Japan, have used computer simulations grounded in evolutionary game theory to demonstrate how intensified environmental variability in Africa during the Middle Stone Age may have promoted the evolution of cooperative behaviour and enhanced cognitive abilities in archaic hominins.

Fundamental to this research is the scientific consensus that Darwinian evolution is the only credible framework for explaining the patterns observed in the fossil record and the genomic evidence for natural selection.

The study also directly challenges a common creationist misrepresentation: that Richard Dawkins’ metaphor of the “selfish gene” implies that evolution inherently favours selfishness and therefore cannot account for altruism or cooperation. This flawed interpretation ignores the fact that evolutionary processes often favour cooperative strategies—especially in complex, fluctuating environments—without invoking supernatural causes.

Severe environmental change can fragment populations into small, isolated groups, where genetic drift plays a significant role in evolution. In such settings, beneficial mutations can rapidly drift to fixation, potentially giving the group a competitive advantage over neighbouring populations when contact is re-established. This process can produce a pattern in the fossil record that resembles 'punctuated equilibrium', with the apparent 'sudden' appearance of a major innovation.

Tuesday, 25 March 2025

Refuting Creationism - Common Origins - Like Humans, Chimpanzees Use Engineering Skills to Make Tools

Not so long ago, it was commonly claimed that humans were exceptional due to their supposedly 'unique' ability to make and use tools. This assertion was often used to reinforce the idea that humans occupied a special position at the pinnacle of creation, justifying the biblical concept of human dominion over the rest of nature.

However, this claim was never credible to anyone observing nature carefully. It was largely promoted by religious authorities to foster a sense of human uniqueness and importance. This, in turn, reinforced belief in a creator god, supported the authority of religious institutions and their clerics, and justified their claims to the right to create laws governing human behaviour.

Scientific research has increasingly exposed the fallacy of this notion of human exceptionalism. Tool-making and tool use in humans are indeed more sophisticated than in other animals, but this ability is far from unique. Many other species demonstrate these abilities, notably chimpanzees—our closest living relatives. The widespread occurrence of tool use in nature strongly suggests this trait was present in a common ancestor we share with other primates. Furthermore, the independent evolution of tool use in species as diverse as birds, bees, and octopuses demonstrates that this capability is not unique to humans but rather a result of natural evolutionary processes.

Another human characteristic, traditionally cited by religious authorities as evidence for special creation and human exceptionalism, has, once again, been shown by science to be better explained as evidence of our evolutionary heritage within the natural world.

And today we have evidence that chimpanzees not only make and use tools but employ sophisticated 'engineering' skill in their choice of the right materials for their construction. It comes in the form of a paper published, open access, in iScience by a team of researchers led by Dr Alejandra Pascual-Garrido, of the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford, UK.

Friday, 24 January 2025

Refuting Creationism - Our Ancesters Were Vegetarian, 3 Million Years Before 'Creation Week'

Three million years ago, our ancestors were vegetarian - Wits University

The Australopithecus genus is widely regarded as the immediate ancestor of the Homo genus that includes modern humans, Homo sapiens, but, from new evidence revealed by a team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany and the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, it appears that meat did not become part of our immediate ancestors' diet until after Homo species emerged.

The evidence comes from an isotope analysis of the enamel from the fossilised teeth of seven Australopithecus individuals is strongly indicative of a vegetarian diet with little or no meat consumption.

How they discovered this is the subject of a paper in Science and a new item from Witwatersrand University. Creationists should note that the isotopes of nitrogen on which this analysis is based are stable, so the traditional excuse that radioactive decay rates have changes over time is not relevant here. Besides, they are not the basis of dating these fossils, but of working out where in the food chain these Australopithecines were:

Monday, 13 January 2025

Refuting Creationism - Ability to Perform Complex Tasks Had Already Evolved Before Chimps and Hominins Split

Study shows that chimpanzees perform the same complex behaviours that have brought humans success | University of Oxford

Time and again, science is showing that characteristics which were once considered uniquely human, and therefore, according to creationists, evidence that humans are a special creation, distinct from all other animals, are in fact shared with other animals.

Instead of being evidence of unique creation, they are evidence of common origins and descent with modification.

On such human characteristic is the ability to perform complex tasks, involving tool use, in organised sequence, and adapt those sequences if necessary to complete the task. In other words, to plan a strategy for achieving a specific goal.

However, a new study has shown that chimpanzees also have this ability, suggesting it was present in the common ancestor before chimps and Hominins diverged some 6 million years ago.

Friday, 10 January 2025

Common Origins - How The Mammalian Outer Ear Evolved - From Our Ancestral Fish Gills

An earful of gill: USC Stem Cell study points to the evolutionary origin of the mammalian outer ear | USC Stem Cell

I'm sorry if this spoils a creationists new year, but a bunch of scientists from the Stem Cell Lab of the University of Southern California have just published a paper showing an ancient ancestor of mammals, including of course us humans, was a fish.

It comes in the form of evidence that our outer ear develops from the same tissues in the embryo as the gills of fish. These tissues have been exapted by evolution for many new structures, one of which is the outer ear of mammals.

Sunday, 8 December 2024

Refuting Creationism - How the 'Lizard' Part of Your Brain Influences Your Thinking

Few things upset creationists more than evidence that they are not only apes and share a common ancestor with the other African apes, but that they also share a common ancestor even with non-mammals such as reptiles, and yet, as the American evolutionary biologist, Theodosius Dobzhansky reminds us, nothing in biology makes sense without the Theory of Evolution (TOE).

And one thing that does make sense is how the human brain is the result of an evolutionary process with ancestry in those common ancestors, including lizards.

A second thing that creationists who have deluded themselves into believing that mainstream biomedical scientists are giving up on the TOE and adopting the childish notion of intelligent design, will find distressing, is the news that the team who did this piece of research are firmly convinced that the structure of our brain and the way it works is the result of evolution, not magic.

The third thing is how this explains empathy, of which creationists often feign ignorance, claiming they get their sense of right and wrong from their invisible friend and have a handbook to tell them how to behave. The curious belief that even influenced supposed Christian intellectual 'giants' such as the smugly self-satisfied, C.S. Lewis, is despite the fact that one of the Golden Rules of human society, that even the founder of Christianity, Jesus, allegedly told his followers to apply - "Do unto others what you would they do unto you" or words to that effect, depend entirely on having the empathetic ability to know what someone else would want.

The research explains how this ability in humans comes from an ancestral ability to read social signals and form relationships, including an understanding of social hierarchies, possessed even by lizards.

Thursday, 7 November 2024

Common Origins - Marmoset and Human Brain Development

Creationists like to pretend there is nothing in common between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom because humans were magically created as the special creation of a god who made all the 'lower' animals for our use, then gave us dominion over everything. This makes creationists feel really important.

The truth however is that we have very much in common with other animals and particularly with the species to which we are most closely relates and with whom we share the most recent common ancestor as we and they evolved and diversified over the same period of time to arrive at our present state.

This is reflected in the nested hierarchies into which the different branches of the evolutionary tree can be arranged in, anatomy, physiology and DNA and in the way our bodies develop through embryology and continued into childhood.

And yet creationists insist we are not only a different species, but a different 'kind' of animal, even a different category of life altogether, even though none of the difference they insist apply to different taxons as evidence of evolution apply to humans in respect of the other great apes.

The common marmoset, Callithrix jacchus, and their evolutionary relationship to humans. The common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) is a small primate species native to the forests and scrublands of northeastern Brazil. Known for its expressive face, tufted ears, and squirrel-sized body, it’s a popular species for scientific research, primarily because it shares some interesting genetic and behavioural traits with humans. Here’s an overview of its characteristics, behaviour, and evolutionary relationship with humans.Now, as though to drive another nail into the coffin of that primitive superstition, scientists have just shown how the brains of humans and the common marmoset monkey follow parallel development, demonstrating their common origins.

Physical Characteristics

- Size: Common marmosets are small, weighing only about 300-400 grams, with a body length of 7-10 inches (18-25 cm) and a long, bushy tail.

- Appearance: They have a distinctive look with white ear tufts, a small face, and wide eyes. Their fur is mostly brownish-grey with a mix of white and black, allowing them to blend into their arboreal habitat.

- Hands and Feet: Like other New World monkeys, they have claws on most fingers (rather than flat nails like humans), which helps them cling to trees.

Habitat and Diet

- Environment: Marmosets thrive in forests, especially in areas with dense foliage where they can find food and avoid predators. They’re highly adaptable and can be found in both natural and urbanized settings in Brazil.

- Diet: They’re omnivores, feeding on tree sap, insects, fruits, and small animals. They use their specialized incisor teeth to gouge tree bark and access sap, which is a key component of their diet.

Social Structure and Behaviour

- Social Groups: Marmosets live in family groups typically led by a dominant pair. Groups consist of 5-15 individuals, often including multiple generations, with cooperative care of young by both parents and other group members.

- Communication: Marmosets are highly social and communicate through vocalizations, scents, and body language. They produce different calls depending on the context, and some sounds are ultrasonic, beyond human hearing range.

- Reproduction: These primates have a unique reproductive system, where dominant females can suppress the reproduction of other females in the group. They often give birth to twins, and group members assist in raising the young, a rare behaviour in mammals that echoes human familial cooperation.

Relationship to Humans

Marmosets belong to the infraorder Simiiformes, which includes all monkeys and apes, meaning they’re more distantly related to humans than other primates like chimpanzees and gorillas, who are part of the hominoid lineage. However, they still share significant genetic similarities with humans—about 92% of their DNA. They’re one of the smallest primates often studied for insights into human aging, neurological diseases, and genetics because of several interesting parallels:

- Brain and Behaviour: While their brains are much smaller than humans', they share many structural and functional aspects, including similar regions that govern emotions, memory, and sensory processing.

- Lifespan and Aging: Marmosets age quickly for a primate, with a lifespan of around 12-16 years. They exhibit aging patterns similar to humans, including changes in the immune system, body mass, and cognitive abilities, which is valuable in studying aging processes.

- Social and Parenting Behaviours: Cooperative parenting and close social bonds within groups mirror certain aspects of human social structures.

Conservation Status

The common marmoset is currently listed as "Least Concern" by the IUCN, though habitat loss and pet trade are concerns. They adapt well to different environments, which has helped their survival, but their populations are still vulnerable to ecological changes.

In summary, while common marmosets diverged from humans over 40 million years ago, their unique traits and social behaviours make them a valuable species for understanding certain aspects of human biology and psychology, providing insight into genetic, neurological, and social characteristics that bridge the gap between humans and other primates.

Common marmosets and humans have similar prolonged periods of childhood where child care is shared amongst several adults, so the children experience intense socialisation as they develop juts as human children do, and because their brains are fundamentally the same as human brains, the same areas develop in the same way and at the same stage in their development:

Similarities in Brain Development Between Marmosets and Humans

In common marmosets, the brain regions that process social interactions develop very slowly, extending until early adulthood, like in humans. During this time, all group members are involved in raising the infants, which contributes to the species’ strong socio-cognitive skills.

The development of primate brains is shaped by various inputs. However, these inputs differ between independent breeders, such as great apes, and cooperative breeders, such as the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) and humans. In these species, group members other than the parents contribute substantially to raising the infants from birth onwards.

A group of international researchers led by Paola Cerrito from the University of Zurich’s Department of Evolutionary Anthropology studied how such social interactions map onto brain development in common marmosets. The study provides new insights into the relationship between the timing of brain development and the socio-cognitive skills of marmosets, in particular their prosocial and cooperative behaviours.

Prolonged learning from social interactions

The research team analysed brain development using magnetic resonance data and showed that in marmosets, the brain regions involved in the processing of social interactions exhibit protracted development – in a similar way to humans. These brain regions only reach maturity in early adulthood, allowing the animals to learn from social interactions for longer.

Like humans, immature marmosets are surrounded and cared for by multiple caregivers from birth and are therefore exposed to intense social interaction. Feeding is also a cooperative business: the immature animals are fed by group members and as they get older they have to beg for food because their mothers are already busy with the next offspring. According to the study, the need to elicit care from several group members significantly shapes brain development and contributes to the sophisticated socio-cognitive motivation (and observed skills) of these primates.

A model for human evolution

Given their similarities with humans, marmosets are an important model for studying the evolution of social cognition.

Our findings underscore the importance of social experiences to the formation of neural and cognitive networks, not only in primates, but also in humans. This insight could have an impact on various fields, ranging from evolutionary biology to neuroscience and psychology.

Paola Cerrito, first author

Department of Evolutionary Anthropology

University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland.

The early-life social inputs that characterize infants’ life in cooperatively breeding species may be a driving force in the development of humans marked social motivation.

Publication:

If the brains of humans an marmosets are fundamentally similar and develop the same way, perhaps a creationist could explain in what way, apart from their tail and their claws in place of human flat finger nails, marmosets are a different 'kind' to humans, and then explain why the same reasoning doesn't place the great apes in the same 'kind' as humans.Abstract

Primate brain development is shaped by inputs received during critical periods. These inputs differ between independent and cooperative breeders: In cooperative breeders, infants interact with multiple caregivers. We study how the neurodevelopmental timing of the cooperatively breeding common marmoset maps onto behavioral milestones. To obtain structure-function co-constructions, we combine behavioral, neuroimaging (anatomical and functional), and neural tracing experiments. We find that brain areas critically involved in observing conspecifics interacting (i) develop in clusters, (ii) have prolonged developmental trajectories, (iii) differentiate during the period of negotiations between immatures and multiple caregivers, and (iv) do not share stronger connectivity than with other regions. Overall, developmental timing of social brain areas correlates with social and behavioral milestones in marmosets and, as in humans, extends into adulthood. This rich social input is likely critical for the emergence of their strong socio-cognitive skills. Because humans are cooperative breeders too, these findings have strong implications for the evolution of human social cognition.

INTRODUCTION

Strong social cognition and prosociality are, from a very young age, hallmarks of the human mind compared to the closest living relatives, the nonhuman great apes (1). Because of our peculiar life history, characterized by early weaning and extensive allomaternal care starting from very early in infancy, human development is embedded in a world filled with other individuals, including parents, siblings, and other family members. Thus, this is the context in which human toddlers’ strong social cognition and prosociality develops (2). It is this same period that is also the most important for the formation of the neural bases of higher-order social, emotional, and communicative functions (3). Not unexpectedly then, several independent lines of evidence, spanning neuroscience, pediatrics, primatology, and psychiatry, point to the fundamental role that the relative timing of brain development and social interactions have for the acquisition of social cognition and prosocial behaviors (4).

During ontogeny, total brain volume increases until reaching its adult levels. This volumetric increase is the product of gray matter (GM) volume (GMV) increase until a peak value is reached in childhood, after which it decreases concurrently with synaptic pruning and white matter volumetric increase (5). In addition, the ontogenetic trajectories of cerebral GM are heterochronous, such that both maximum GMV and GM reduction rate vary across brain regions. The importance of the temporal patterns of brain development in shaping the adult phenotype becomes apparent, for example, in the case of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Deviations from the normal range of developmental timing of the cortex can profoundly affect socio-cognitive skills and are one of the main factors linked to the occurrence of ASD (3). Specifically, several studies have found that early brain overgrowth during the first years of life strongly correlates with ASD [e.g. (6)] and a meta-analysis of all published magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data by 2005 revealed that the period of greatest brain enlargement in autism is during early childhood (7), with about a 10% volume increase compared to controls during the first year of life. Hence, individuals affected by ASD present an accelerated early-life brain growth and achieve a final brain volume that is not different from that of controls, but they achieve it earlier than controls. Recent works with human brain organoids has confirmed the accelerated maturation of the cortex in the ASD phenotype, especially interneurons (8, 9). Consequently, given this accelerated early-life brain development, fewer social inputs are available during the period when the GMV reduces to adult size and differentiates via experience-dependent pruning. Accelerated development of functional connectivity between certain brain areas [e.g., amygdala–prefrontal cortex (PFC)] can also be a consequence of early-life stress, which, in turn, can cause adverse physiological conditions such as increased anxiety and cortisol levels (10). Unfortunately, so far, nothing is known regarding the impact of changes in brain developmental timing within nonhuman species. That is, we do not know if, within a given nonhuman species, alterations in ontogenetic trajectories of the brain have an impact on the adult behavioral phenotype. However, comparative studies across species with different ontogenetic trajectories and social behaviors can help us shed light on the relationship between the two.

The importance of social inputs occurring during prolonged brain maturation and slow developmental pace has also been highlighted in the context of human evolutionary studies. The remarkable brain growth and development occurring postnatally in humans arguably allows the brain to be influenced by the social environment outside of the uterus to a greater extent than that seen in other great apes (11), who are not cooperative breeders (12). Hawkes and Finlay (13) show that, in addition to weaning our infants earlier than expected (based on allometric scaling with other life-history variables), human neonates have an especially delayed neural development, which is likely correlated with the energetic trade-offs stemming from the large size and high caloric demand of our brain (14). In addition, we observe that, in humans, compared to other great apes, myelination is much prolonged and continues well into adulthood (15).

Common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) are cooperatively breeding platyrrhine monkeys. Like humans, but unlike other great apes (12), they rely on extensive allomaternal care and share many life-history traits (e.g., short interbirth intervals and a hiatus between menarche and first reproduction) with humans (16). They also show remarkable prosociality (4, 15) [much more than great apes (16)] and strong socio-cognitive abilities, which have been argued to correlate with cooperative breeding (17–20). However, the neurobiological features underlying the socio-cognitive abilities promoting the prosocial behavior are poorly understood. Moreover, experimental research has shown that, in common marmosets (hereafter marmosets), there is a critical period for the development of social behaviors (21), although the relationship between developmental timing of the brain and these early-life social interactions is poorly understood.

Given these similarities with humans, marmosets are becoming an ever-more important model in neuroscience (22–25) and particularly in research investigating the neurobiological and neurodevelopmental bases of social cognition. As in humans, immature marmosets are surrounded and cared for by multiple caregivers from the first day on. The entire family is typically present during birth, and oxytocin levels increase not only in mothers but also in all group members (26). Group members contribute appreciably to carrying the infants and, once infants start eating solid food, frequently share food with them. After a peak provisioning period, adults are increasingly less willing to share food with them (27–29). During this period, intense and noisy negotiations over food are frequent, with immatures babbling and begging and adults eventually giving in—or not. Intriguingly, when doing so, immatures appear to take into account how willing individual adults are to share and will insist in more and longer attempts with adults who are generally less likely to refuse them. Soon after, immatures have to compete for attention and food not only with their twin sibling but also with the next offspring that are born far before they themselves are independent because, like in humans, marmosets are weaned early and mothers have their next offspring soon after (30). By now, the immatures still have not reached puberty; this only happens shortly before yet another set of younger siblings is born. Typically, with these new arrivals, the immatures start to act as helpers themselves and thus face the developmental task of switching from being a recipient of help to becoming a provider of help and prosocial acts (31). This is thus the developmental context in which marmosets’ socio-cognitive skills develop.

The goal of this study is to map these behavioral milestones specific to a cooperatively breeding primate to its region-specific brain development to better understand the social interactions in which infants engage during the differentiation period of brain regions selectively implicated in processing social stimuli. Our working hypothesis is that, like in humans, social interactions with several caregivers during this critical period profoundly contribute to the co-construction of the marmoset brain, the maturation of socially related associative areas, and therefore the emergence of prosocial behaviors. For that purpose, we sought to determine if there is a relationship between the temporal profile of the developing marmoset brain and the early-life social interactions that may help explain their sophisticated socio-cognitive skills at adulthood.

To compare the timing of brain development to that of these behavioral milestones and developmental tasks of attaining nutritional independence, we focused on brain regions that, in adult marmosets, are selectively activated by the observation of social interactions between conspecifics but not by multiple but independently behaving marmosets, as identified by Cléry et al. (32). We tested if these brain regions share similar developmental trajectories based on the developmental patterns of regional GMV. To potentially reveal a coordinated ontogenetic profile underlying the “tuning” of the social brain in marmosets, we then compared these neurodevelopmental patterns to longitudinal data of infant negotiations with caregivers in relation to food (as measured by the frequency of food begging). Last, because it is known that brain regions whose activations correlate with performance on a given task strengthen and get fine-tuned with age (33, 34), we assessed if there is stronger connectedness between areas that develop according to similar developmental trajectories and share similar response to social interaction stimuli.

We thus combined several types of previously published data from marmosets to provide a unified picture of structural brain development alongside the development of social interactions between infants and multiple caregivers necessary to ensure survival (infant provisioning). These included structural MRI (sMRI) data of GM of 53 cortical areas and 16 subcortical nuclei acquired from a developmental cohort (aged 13 to 104 weeks) of 41 male and female marmosets (35), functional MRI (fMRI) data mapping the brain areas activated by the observation of social interactions in marmosets (32), food sharing interactions in five family groups of marmosets including a total of 26 adults and 14 immatures [from 1 to 60 weeks of age (27)], and cellular-resolution data of corticocortical connectivity in marmosets obtained via 143 retrograde tracer injections in 52 young adult marmosets of both sexes (36).

Overall, we make the following predictions:

- P1: Cortical regions that show significantly stronger activation during the observation of social interactions (32) share similar structural neurodevelopmental profiles, which are distinct from those regions showing significantly stronger activation during the observation of nonsocial activities.