How 'Selfish' Genes Can Act Like Killer Parasites

Stowers scientists uncover… | Stowers Institute for Medical Research

As Richard Dawkins explained in his influential book, The Selfish Gene, all genes can be thought of as "selfish" in the sense that natural selection favours those most effective at surviving and replicating. Such genes persist over generations at the expense of rival alleles. Even when genes form cooperative alliances, as they commonly do, it ultimately serves their own evolutionary success. Of course, genes are merely chemical entities - mindless, emotionless, and incapable of intention or planning - so the concept of "selfishness" is simply a metaphor designed to illustrate gene-cantered evolution.

However, within the genomes of many multicellular organisms, certain genes can more literally be described as selfish. These genes act parasitically, exploiting the host cell’s replication machinery solely to propagate themselves, despite having no beneficial function and often harming their host by reducing its fertility. The mechanisms behind this parasitic behaviour have puzzled scientists since these genes were first discovered.

Do you have any examples of these 'selfish' genes and information on their origins and evolutionary history?The presence of these genes challenges the creationist notion of intelligent design, since no designer worthy of the adjective 'intelligent' would include genes with no function that can even be harmful. The Theory of Evolution, on the other hand, offers a perfect explanation for their existence as the remnants of former functional genes, or the result of horizontal gene transfer at some point in the distant evolutionary history of the host organism.Certainly! Here are some classic examples of these "selfish" genetic elements, along with their origins and evolutionary histories:

- Segregation Distorters (Meiotic Drive Genes)

Example:Description:

- Segregation Distorter (SD) complex in Drosophila melanogaster

- t-haplotype in mice (Mus musculus)

These genes manipulate the process of meiosis to bias inheritance ratios, ensuring they appear in more than 50% of offspring, often harming fertility by causing death or dysfunction in gametes lacking the "selfish" element.

Evolutionary Origin:

Segregation distorters typically arise from mutations that interfere with meiosis and chromosome segregation, enabling them to outcompete other alleles. They represent a classic example of intragenomic conflict, evolving under strong selection pressure due to their ability to cheat standard Mendelian inheritance.

- Transposable Elements (Jumping Genes)

Example:Description:

- Alu elements (primates, including humans)

- LINE-1 retrotransposons (humans and other mammals)

- P-elements in Drosophila melanogaster

These are sequences of DNA capable of copying themselves and inserting copies into new genomic locations, sometimes disrupting normal gene function or causing harmful mutations. They have no direct benefit to the host organism and can significantly burden the genome, reducing host fitness or fertility.

Evolutionary Origin:

Transposable elements likely originated early in evolutionary history from viral infections or mobile genetic elements introduced into ancestral genomes. Due to their capacity for self-replication, they rapidly colonized genomes across diverse lineages, driving genome expansion and evolution through ongoing "arms races" between genomic suppression mechanisms (e.g., RNA interference) and transposon activity.

- B Chromosomes

Example:Description:

- B chromosomes in grasshoppers, maize, and certain fish species

These are supernumerary chromosomes that are not essential for the host organism’s survival or reproduction. They propagate by mechanisms that bias their inheritance, typically by preferentially entering egg or sperm cells during meiosis.

Evolutionary Origin:

B chromosomes probably arose from normal chromosomes through structural mutations or duplication events. Over time, they have evolved specific mechanisms to preferentially segregate during meiosis, ensuring their persistence despite their neutrality or even harmful effects on host fitness.

- Homing Endonuclease Genes (HEGs)

Example:Description:

- VDE (Vacuolar protein-sorting defective endonuclease) gene in yeast

These genes encode enzymes (endonucleases) capable of cutting DNA at specific recognition sites, triggering cellular repair mechanisms to copy the gene into new locations. They thus "invade" and spread rapidly within a genome.

Evolutionary Origin:

HEGs likely originated as genetic parasites—mobile elements derived from ancestral viral or plasmid sequences. Their endonuclease activity ensures their spread throughout populations by driving inheritance bias.

Evolutionary Significance

Selfish genes, despite being parasitic, can profoundly influence genomic architecture, driving the evolution of genome defence mechanisms, such as RNA interference, DNA methylation, and other epigenetic suppression systems. They represent powerful examples of intragenomic conflict—an evolutionary arms race occurring within the genomes of organisms themselves.

In short, these selfish genetic elements not only reveal the complexities and conflicts inherent in evolution at the genetic level but also illustrate how genome structure and regulation evolve under selective pressures exerted from within, as well as from external environments.

In other words, they are examples of unintelligent design and strongly support the Theory of Evolution.

Exactly. Selfish genetic elements are prime examples of "unintelligent design"—they represent biological systems that no rational designer would intentionally create. Rather, they clearly reflect evolutionary processes driven by genetic conflicts, chance mutations, and selection pressures operating at multiple levels.

Their existence underscores key evolutionary points:

- Imperfect Design:

Selfish genes frequently harm their hosts, reducing fertility or fitness. Such inefficiencies are difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile with the concept of a benevolent, intelligent creator designing life perfectly.

- Evolutionary Arms Races:

Organisms continuously evolve defines mechanisms against these selfish elements (such as RNA interference or DNA methylation). These ongoing battles within genomes highlight an evolutionary history of competition rather than deliberate planning.

- Historical Contingency and Chance:

Selfish genes often emerge through random mutations and are maintained simply because they replicate effectively—not because they're beneficial. This strongly supports the evolutionary narrative of chance events followed by natural selection, rather than purposeful design.

In short, selfish genetic elements powerfully demonstrate evolution as a natural, non-directed process, making them compelling evidence against Intelligent Design and strong support for evolutionary theory.

Now, researchers at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, Missouri, USA, have uncovered how these "selfish" genes manipulate cellular processes to ensure their transmission to the next generation, frequently at the expense of their host organism's fertility.

Stowers scientists uncover principles underlying the toxicity of “selfish” genes

Lurking within the genomes of nearly all species—including plants, fungi, and even humans—are genes that are passed from generation to generation with no clear benefit to the organism. Called “selfish” genes, they can sometimes be harmful or even lethal. A recent study from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research sheds new light on how selfish genes “cheat” inheritance to ensure they are passed to the next generation, often at the expense of an organism’s fertility.

The collaboration between the labs of Associate Investigators SaraH Zanders, Ph.D., and Randal Halfmann, Ph.D., investigated these selfish genes in fission yeast, a single-celled organism and powerful system for genetic research. The teams uncovered common principles in how the widely variable wtf selfish gene family harms cells, and these properties likely exist across many forms of life. Published in PLoS Genetics on February 18, 2025, the findings reveal that the ability of these selfish genes to rapidly evolve contributes to their long-term evolutionary success yet can also occasionally lead to their own self-destruction. Selfish genes operate by “driving” or favoring their own transmission during reproduction. The most extreme class, called killer meiotic drivers, create toxic proteins that destroy reproductive cells—except for those that inherit the gene that are saved by also making a protein “antidote.”

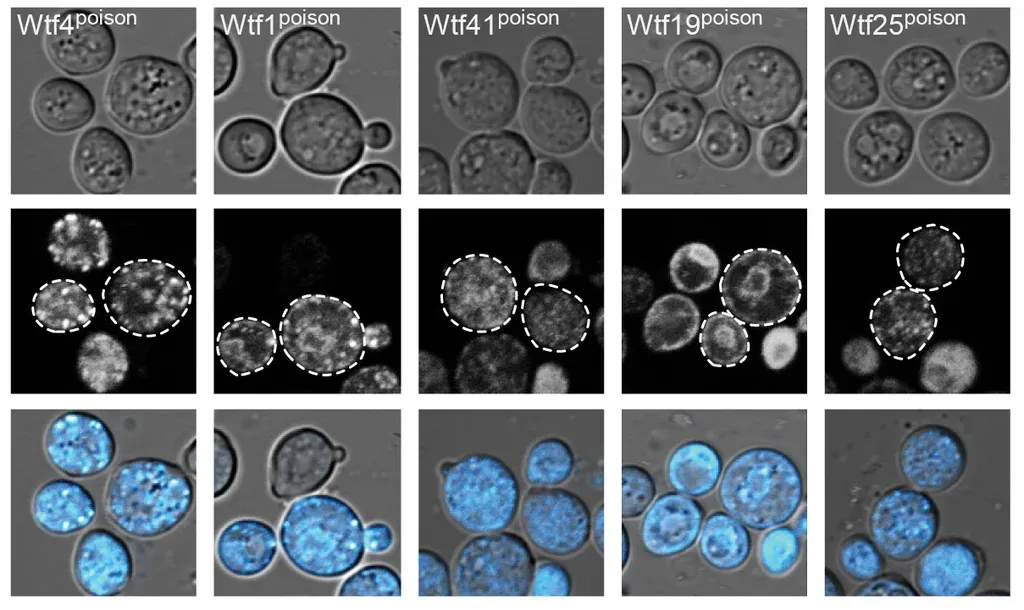

This research expands on a previous study describing how one wtf gene (wtf4) is passed on from generation to generation. The current study, led by Predoctoral Researcher Ananya Srinivasa Nidamangala from the Zanders Lab, explored whether all functional wtf genes—there are hundreds—rely on similar molecular mechanisms and which protein features were necessary for function. Fluorescent microscopy images of highly variable wtf genes’ poison proteins (Wtfpoison) exhibit similar aggregation and distribution within yeast cells.

Fluorescent microscopy images of highly variable wtf genes’ poison proteins (Wtfpoison) exhibit similar aggregation and distribution within yeast cells.

Several key discoveries emerged. The killing ability of wtf genes originates from the way Wtf poison proteins aggregate or form clusters. Their matching antidotes also cluster together, and the poison and antidote must co-assemble to rescue developing gametes, or reproductive cells. These self-assembly properties resemble those of other proteins capable of forming toxic clusters, such as those implicated in neurodegenerative diseases.Proteins that self-assemble into aggregates play important cellular roles but are also linked to diseases like Alzheimer’s. Our work adds to our understanding of fundamental biological questions—which protein sequences favor aggregation and what distinguishes aggregates as toxic or non-toxic.

Sarah E. Zander, lead author

Stowers Institute for Medical Research

Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

Size matters. So does location.

The teams used the Schizosaccharomyces kambucha yeast isolate, isolated from the effervescent beverage, kombucha, as a system to study Wtf protein properties. Proteins were measured with DAmFRET, a technique developed in the Halfmann Lab that detects aggregation. The researchers discovered that all functional wtf genes share the Wtf4 proteins’ self-assembly capabilities, a surprising finding given the extreme variability of the genes’ sequences and the proteins they make.

Graphical illustration showing rules for effective and ineffective neutralization of poison proteins. Yeast cells are “rescued” when wtfpoison and wftantidote specifically co-assemble and localize toward the vacuole (left panel). Otherwise, yeast cells are destroyed (right panels).

Graphical illustration showing rules for effective and ineffective neutralization of poison proteins. Yeast cells are “rescued” when wtfpoison and wftantidote specifically co-assemble and localize toward the vacuole (left panel). Otherwise, yeast cells are destroyed (right panels).

The researchers then assessed what makes proteins toxic. They designed mutant Wtf poison proteins to alter aggregate size and their distribution within cells. Larger clusters were less toxic than smaller ones, and global distribution within cells was required for killing.

Our findings strongly implicate aggregation and protein localization as key factors for toxicity …just sticking the proteins together is insufficient.

Sarah E. Zander.

The antidote protein was known to transport poison protein clumps to the vacuole, a cell’s version of a trashcan, for disassembly and disposal. Previously, researchers thought that the poison-antidote cluster simply served as a tether. Now, the researchers found that a specific poison-antidote co-assembly, which increases aggregate size and isolates it, is necessary for neutralization.

This work is confirming an emerging paradigm underlying toxicity—aggregate size and distribution within a cell matters. Our lab focuses on how proteins self-assemble, particularly those involved in neurodegenerative diseases. By applying our knowledge and tools to the poison-antidote mechanisms in yeast meiotic drive genes, we could see clear parallels of what makes self-assembling proteins toxic and more importantly how they can be detoxified.

Randal Halfmann, co-author

Stowers Institute for Medical Research

Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

An evolutionary arms race

The dynamic interplay of sabotage and salvation lends an almost cinematic touch to yeast’s evolutionary plot. The rapid evolution of wtf drivers have enabled them to outrun suppressor genetic elements for over 100 million years. However, the researchers found that mutations can and do occur in nature, giving rise to “self-killing” gene copies that totally destroy fertility of organisms carrying the gene.

We demonstrate that crazy different Wtf protein sequences can all somehow make aggregates. Evolution goes with what works, and this job of efficient killing works. The striking thing to me is how these super different proteins all execute this same task, and that's something that we'll continue to explore going forward.

A major driver of rapid genome evolution are genetic conflicts. Understanding the conflicts introduced by wtf genes is shedding light on fission yeast genome evolution, but similar dynamics, similar arms races, similar conflicts are happening throughout other organisms and have shaped our own genomes as well. This study opens the door for future research into how protein aggregation influences infertility, evolution, and disease.Sarah E. Zander.

Additional authors include Samuel Campbell, Shriram Venkatesan, Ph.D., Nicole Nuckolls, Ph.D., and Jeffery Lange, Ph.D.

AbstractIt is difficult to comprehend how biologists such as Michael J. Behe can continue to argue for an omniscient, supreme intelligence as the architect of genes that serve no beneficial purpose and actively harm their host organisms. These parasitic genetic elements possess sophisticated mechanisms designed solely to ensure their own survival within the genome, yet they offer nothing of functional value and often reduce overall organismal fitness.

Killer meiotic drivers are selfish DNA loci that sabotage the gametes that do not inherit them from a driver+/driver− heterozygote. These drivers often employ toxic proteins that target essential cellular functions to cause the destruction of driver− gametes. Identifying the mechanisms of drivers can expand our understanding of infertility and reveal novel insights about the cellular functions targeted by drivers. In this work, we explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the wtf family of killer meiotic drivers found in fission yeasts. Each wtf killer acts using a toxic Wtfpoison protein that can be neutralized by a corresponding wftantidote protein. The wtf genes are rapidly evolving and extremely diverse. Here we found that self-assembly of Wtfpoison proteins is broadly conserved and associated with toxicity across the gene family, despite minimal amino acid conservation. In addition, we found the toxicity of Wtfpoison assemblies can be modulated by protein tags designed to increase or decrease the extent of the Wtfpoison assembly, implicating assembly size in toxicity. We also identified a conserved, critical role for the specific co-assembly of the Wtfpoison and wftantidote proteins in promoting effective neutralization of Wtfpoison toxicity. Finally, we engineered wtf alleles that encode toxic Wtfpoison proteins that are not effectively neutralized by their corresponding wftantidote proteins. The possibility of such self-destructive alleles reveals functional constraints on wtf evolution and suggests similar alleles could be cryptic contributors to infertility in fission yeast populations. As rapidly evolving killer meiotic drivers are widespread in eukaryotes, analogous self-killing drive alleles could contribute to sporadic infertility in many lineages.

Author summary

Diploid organisms, such as humans, have two copies of most genes. Only one copy, however, is transmitted through gametes (e.g., sperm and egg) to any given offspring. Alternate copies of the same gene are expected to be equally represented in the gametes, resulting in random transmission to the next generation. However, some genes can “cheat” to be transmitted to more than half of the gametes, often at a cost to the host organism. Killer meiotic drivers are one such class of cheater genes that act by eliminating gametes lacking the driver. In this work, we studied the wtf family of killer meiotic drivers found in fission yeasts. Each wtf driver encodes a poison and an antidote protein to specifically kill gametes that do not inherit the driver. Through analyzing a large suite of diverse natural and engineered mutant wtf genes, we identified multiple properties—such as poison self-assembly and poison-antidote co-assembly—that can constrain poison toxicity and antidote rescue. These constraints could influence the evolution of wtf genes. Additionally, we discovered several incompatible wtf poison-antidote pairs, demonstrating expanded potential for self-killing wtf alleles. Such alleles could potentially arise spontaneously in populations cause infertility.

Introduction

Genomes often contain selfish DNA sequences that persist by promoting their own propagation into the next generation without providing an overall fitness benefit to the organism [1,2]. Killer meiotic drivers are one class of selfish sequences that act by preferentially destroying gametes that do not inherit the driver from a heterozygote [3]. This gamete destruction leads to biased, or sometimes, complete transmission of the driver+ genotype from driver+/driver− heterozygotes. Killer meiotic drive systems generally decrease the fitness of the organism carrying the driver, both through their killing activities and through indirect mechanisms [4].

Distinct killer meiotic drive systems have repeatedly evolved in eukaryotes and drivers found in distinct species are generally not homologous [3,5–12]. Despite this, killer meiotic drivers fall into a limited number of mechanistic classes with shared themes [3,13,14]. Additionally, unrelated killer meiotic drivers have recurrently exploited conserved facets of cell physiology. This has enabled study of the killing and/or rescue activities of drive proteins outside of their endogenous species [5,11,15,16]. Overall, drivers represent unique tools that can be used to discover novel, unexpected insights into the exploited biological processes.

The wtf genes are a family of extremely diverse, rapidly evolving killer meiotic drivers found in multiple copies in most Schizosaccharomyces (fission yeast) species [17–22]. The wtf driver genes each produce a Wtfpoison and a wftantidote protein using distinct transcripts with overlapping coding sequences (Fig 1A) [17,22,24]. The amino acid sequences of the two proteins are largely identical, except the wftantidote proteins have an additional N-terminal domain of about 45 amino acids not found in the Wtfpoison (Fig 1A). All four developing spores (products of meiosis) are exposed to the Wtfpoison, but only spores that inherit a compatible wftantidote can neutralize the poison and survive [22].

Fig 1. Features of wtf4 and mutant alleles.

Fig 1. Features of wtf4 and mutant alleles.

A. A cartoon of S. kambucha wtf4 coding sequence (CDS). Wft4antidote coding sequence is shown in magenta, which includes exons 1–6. The Wtfpoison coding sequence is shown in cyan, which includes 21 base pairs from intron 1 (in grey), and exons 2–6. B. Features of Wft4antidote and Wtf4poison proteins. Row 1 shows predicted secondary structure domains and functional motifs, including PY motifs (in mustard) and predicted transmembrane domains (in red). Row 2 shows the coding sequence repeats in exon 3 and exon 6. Row 3 highlights a well-conserved region 9 amino acids long. Row 4 is the normalized hydrophobicity of the Wtf4 proteins from ProtScale, with the Kyle and Doolittle Hydropathy scale [23]. The higher the number on the scale, the higher the hydrophobicity of the amino acid. See S5 and S6 Tables for detailed descriptions. C. Percentage amino acid identity of wftantidotes from 33 wtf driver genes from four isolates of S. pombe [20]. The antidote sequences were aligned using Geneious Prime (2023.0.4) and the percentage amino acid identity is depicted as a heatmap, with yellow being 100% identity. S. kambucha wtf4 CDS is shown below for comparison, with the exons labeled corresponding to the consensus. Labeled areas within exons 3 and 6, where identity is low, represent the expansion and contraction of the coding sequence repeats of different wtf genes. D. Cartoon of wtf4 mutants constructed in this study. Each mutant category was constructed based on a specific feature mentioned above. The categories are depicted with a wild type wtf4 allele at the top. See S1 Table for a comprehensive overview of the alleles and their phenotypes.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1011534.g001

Little is known about the mechanism of toxicity of the Wtfpoison proteins. The general mechanism used by wftantidote proteins is better understood. The antidote-specific N-terminal domain is the most conserved region and includes targeting motifs (PY motifs) that are recognized by Rsp5/NEDD4 ubiquitin ligases which route the protein through the trans Golgi network to endosomes and, ultimately, to the vacuole (fungal lysosome; Fig 1B) [15,25]. When both proteins are present, the wftantidote co-assembles with the Wtfpoison, and the wftantidote thereby traffics the Wtfpoison to the vacuole [15,25]. This mechanism is similar to a non-homologous drive system recently described in rice, where an antidote protein rescues the gametes that inherit the drive locus from a toxic poison protein by co-trafficking the poison to the autophagosome [5].

In general, the poison protein encoded by one wtf gene is not compatible with (i.e., neutralized by) the antidotes of widely diverged wtf genes [17,19,26]. However, Wtfpoison proteins can be neutralized by wftantidote proteins encoded at different loci if the sequences are identical or highly similar (outside of the antidote-specific N-terminal domain; Fig 1A) [17,22,25,27]. Although the examples are limited, similarity at the C-termini of the Wtf poison and antidote proteins may be particularly important for compatibility [15,26,27]. For example, the wtf18-2 allele encodes an antidote protein that neutralizes the poison produced by the wtf13 driver [27]. The Wtf18-2antidote and Wtf13antidote proteins are highly similar overall (82% amino acid identity) and identical at their C-termini. Interestingly, the antidote encoded by the reference allele of wtf18 is not identical to Wtf13poison at the C-terminus and does not neutralize it. In addition, swapping one amino acid for two different amino acids in the C-terminus of Wtf18-2antidote (D366NN mutation) to make it more like the reference Wtf18antidote abolishes the protein’s ability to neutralize Wtf13poison [27]. Still, the rules governing poison and antidote compatibility are largely unknown.

While it is clear that a functional wtf driver kills about half the spores produced by wtf+/wtf- heterozygotes, the full impacts of wtf gene evolution on the fitness of populations is not clear. Because the wtf genes encode the poison and antidote proteins on overlapping coding sequences (Fig 1A), novel poisons can emerge simultaneously with their corresponding antidotes via mutation. This has been observed with a limited number of engineered wtf alleles, and one can observe evidence of this divergence in the diversity of extant wtf alleles in natural populations [15,19–21,27]. The natural alleles, however, represent a selected population and thus provide a biased sample of the novel wtf alleles generated by mutation and recombination. Novel alleles that generate functional drivers are predicted to be favored by the self-selection enabled by drive and be over-represented in natural populations. Conversely, alleles that generate a toxic poison without a compatible antidote would be expected to be under-represented in natural populations due to infertility caused by self-killing.

Major questions remain about the mechanism(s) of Wtfpoison toxicity and about the rules of Wtfpoison and wftantidote compatibility. Our working model is that the toxicity of Wtfpoison proteins is tied to their self-assembly [15]. This assembly, however, has only been conclusively demonstrated for the Wtf4 proteins, encoded by the wtf4 gene from the isolate of S. pombe known as kambucha. For wftantidote function, a working model is that a similar homotypic assembly with the Wtfpoison is required to establish a physical connection between the proteins so that the poison is shuttled to the vacuole along with a ubiquitinated antidote [15,25]. The ubiquitination and trafficking of the Wtf antidotes to the vacuole has been demonstrated to be conserved between widely diverged wftantidote proteins [19,25]. However, it is not clear if antidote co-assembly with a poison has a functional role in poison neutralization, or if it merely provides a physical link between the proteins to facilitate co-trafficking. It is also unclear if changes in the coding sequence shared by the poison and antidote proteins of a given wtf can generate an incompatible set of proteins, or if poisons will always be neutralized by sequence-matched antidotes.

To test these models and to better understand the amino acid sequences that support the Wtf protein functions, we analyzed a panel of natural and engineered Wtf proteins. We found that both well-conserved and poorly conserved amino acid sequences can contribute to protein function. Our analyses revealed broad conservation of Wtfpoison self-assembly and suggest that assembly size can affect Wtfpoison toxicity, analogous to several other self-assembling toxic proteins [28–30]. This strongly implicates self-assembly as a critical parameter in Wtfpoison toxicity. In addition, we found that specific co-assembly with the wftantidote is required for efficient Wtfpoison neutralization via trafficking to the vacuole. Finally, our analyses identified multiple wtf alleles that generate poison proteins that are not efficiently neutralized by their corresponding antidotes. Such alleles are self-destructive and could contribute to sporadic infertility. This work refines our understanding of the functional constraints of Wtf proteins, with important evolutionary implications. More broadly, our observations offer insight into how functional conservation can be maintained despite extreme amino acid sequence divergence and extends our understanding of the limits of protein assembly trafficking mechanisms.

Nidamangala Srinivasa A, Campbell S, Venkatesan S, Nuckolls NL, Lange JJ, Halfmann R, et al. (2025)

Functional constraints of wtf killer meiotic drivers.

PLoS Genet 21(2): e1011534. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1011534

Copyright: © 2025 The authors.

Published by PLoS. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Similarly, William A. Dembski argues that any biological structure or gene with a clearly defined, functional role must have been deliberately and intelligently designed. Yet he either remains unaware of these detrimental parasitic genes or intentionally disregards them because they do not fit comfortably within his theory.

An impartial and rational examination of the evidence strongly suggests the absence of any intelligent involvement in the origin of these genetic elements and instead supports the view that they arose through undirected, mindless evolutionary processes.

And while the notion of intelligent design is incomprehensible as an explanation for phenomena such as this, the Theory of Evolution remains the only scientific theory capable of making any sense of it. So much for the childish notion that biologists are about to abandong the TOE infavour of the magical notion of intelligent design creationism.

The Malevolent Designer: Why Nature's God is Not Good

Illustrated by Catherine Webber-Hounslow.

The Unintelligent Designer: Refuting The Intelligent Design Hoax

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.