Gigantic Jurassic pterosaur fossil unearthed in Oxfordshire | University of Portsmouth

The body of one of these monsters ended up buried in Kimmeridge Clay before that too became buried beneath alluvial gravel deposits forming in the proto-Thames valley around my adopted hometown of Abingdon.

Part of the fossilised skeleton, in the form of a partial left wing first phalanx (finger), was recovered in 2022 when a pit was being dug in the clay to form a sump and bank enclosure to replace the removed gravel in an open-cast gravel pit a few miles south of Abingdon. This has now been identified as an adult ctenochasmatoid - a group of pterosaurs known for their long, slender wings, long jaws and fine bristle-like teeth - by experts from Portsmouth and Leicester Universities.

How it came to be recovered and its significance, is the subject of a brief news release from the University of Portsmouth:

Tell me all About Kimmeridge clay, its age, distribution and how it was formed, please. Kimmeridge Clay is a significant geological formation known for its fossil-rich deposits and importance in the study of Earth's history. Here are the details about its age, distribution, and formation:

Age

Kimmeridge Clay is from the Upper Jurassic period, specifically from the Kimmeridgian stage, which dates back approximately 157 to 152 million years ago. This period was characterized by warm, shallow seas and rich marine life.

Distribution

Kimmeridge Clay is primarily found in the following regions:Formation

- United Kingdom It is most famously exposed in the cliffs of Kimmeridge Bay in Dorset, along the Jurassic Coast, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The clay is also found in various parts of southern and eastern England, including the Weald Basin, the Wessex Basin, and the North Sea basin.

- North Sea Extensive deposits are found beneath the North Sea, where it serves as an important source rock for oil and gas exploration.

- Western Europe Similar deposits have been identified in other parts of Western Europe, including France (particularly in the Paris Basin), Germany, and the Netherlands.

Kimmeridge Clay was formed during the Upper Jurassic period in a series of shallow marine environments. The formation process involved several key factors:Importance

- Sediment Deposition The clay was deposited in low-energy marine environments, where fine particles of mud and clay settled out of the water. This created thick layers of sediment that would eventually compact into claystone.

- Organic Matter The waters where Kimmeridge Clay was deposited were rich in organic material, including the remains of marine plants and animals. This organic matter became buried within the sediments, contributing to the high organic content of the clay.

- Anoxic Conditions The bottom waters of these depositional environments were often anoxic (lacking oxygen), which helped preserve the organic matter from decay. This is one reason why Kimmeridge Clay is such an important source rock for hydrocarbons.

- Marine Transgressions and Regressions The Jurassic period experienced several transgressions and regressions (advances and retreats of the sea). These cycles influenced the deposition of sediments and organic material, contributing to the variability seen within the Kimmeridge Clay layers.

Kimmeridge Clay is of great geological and economic importance:In summary, Kimmeridge Clay is a crucial geological formation from the Upper Jurassic period, characterized by its rich fossil content and significant role as a source rock for hydrocarbons. Its distribution across the UK, North Sea, and parts of Western Europe, along with its formation in anoxic marine environments, make it a vital subject of study in both paleontology and economic geology.

- Fossils The formation is rich in fossils, including ammonites, bivalves, marine reptiles, and microfossils. These fossils provide valuable insights into the marine ecosystems of the Jurassic period.

- Hydrocarbons Due to its high organic content, Kimmeridge Clay is a significant source rock for oil and gas. The organic material within the clay has, over millions of years, been transformed into hydrocarbons, making it a key target for energy exploration, particularly in the North Sea.

- Stratigraphy Kimmeridge Clay is used as a reference point in the stratigraphy of the Upper Jurassic. Its well-preserved layers provide a detailed record of the environmental conditions and biological communities of the time.

A team of palaeontologists has discovered a fossil of a gigantic flying reptile from the Jurassic period with an estimated wingspan of more than three metres - making it one of the largest pterosaurs ever found from that era. Excavated from a gravel pit near Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, the fossil includes part of the pterosaur’s wing bone, which was broken into three pieces but still well-preserved. Experts from the universities of Portsmouth and Leicester have published a paper on the specimen, which was topographically scanned and identified as belonging to an adult ctenochasmatoid; a group of pterosaurs known for their long, slender wings, long jaws and fine bristle-like teeth.More detail and background to the discovery is to be found in the team's open access paper in the journal Proceedings of the Geologists' Association:

When the bone was discovered, it was certainly notable for its size. We carried out a numerical analysis and came up with a maximum wingspan of 3.75 metres. Although this would be small for a Cretaceous pterosaur, it’s absolutely huge for a Jurassic one! This fossil is also particularly special because it is one of the first records of this type of pterosaur from the Jurassic period in the United Kingdom.

This specimen is now one of the largest known pterosaurs from the Jurassic period worldwide, surpassed only by a specimen in Switzerland with an estimated wingspan of up to five metres.

Professor David M. Martill, corresponding author.

School of the Environment, Geography and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK.

Pterosaurs from the Triassic and Jurassic periods typically had wingspans between one and a half and two metres, so were generally smaller than their later relatives from the Cretaceous period, which could have wingspans of up to 10 metres. However, this new discovery suggests that some Jurassic pterosaurs could grow much larger.

Geologist, Dr James Etienne, discovered the specimen while hunting for fossil marine reptiles in June 2022 when the Late Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay Formation was temporarily exposed in the floor of a quarry. This revealed a number of specimens including bones from ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs and other ancient sea creatures including ammonites and bivalves, marine crocodiles and sharks.

Abfab, our nickname for the Abingdon pterosaur, shows that pterodactyloids, advanced pterosaurs that completely dominated the Cretaceous, achieved spectacularly large sizes almost immediately after they first appeared in the Middle Jurassic right about the time the dinosaurian ancestors of birds were taking to the air.

Dr Dave M. Unwin, co-author.

School of Museum Studies

University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

The paper is published in Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association and the fossil is now housed in the Etches Collection in Kimmeridge, Dorset.

AbstractTraditionally, creationists try to dismiss this sort of evidence that they are wrong because they use a book of myths made up by people who knew nothing of the world outside their small part of the Middle East, as their reference book, by claiming the dating methods are wrong. So, all they need do now is to identify the dating method use to date the location of this fossil in the geological column in the Kimmeridge Clay immediately under the alluvial gravel laid down by the proto-River Thames and explain why it made 10,000 years look like some 155 million years.

The fossil remains of a pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation (Jurassic: Tithonian) of Abingdon, Oxfordshire, central England are identified as a partial left first wing finger phalanx. The elongation of the phalanx and distinctive morphology of the proximal articular region, in particular the square outline of the extensor tendon process, permit the specimen to be assigned to Ctenochasmatoidea. Although fragmentary, it is sufficiently well preserved to determine accurately its dimensions when complete. Morphometric analysis reveals the specimen to represent one of the largest known examples of a Jurassic pterosaur, with an estimated wingspan of at least 3 m, and is one of the first pterodactyloids to be reported from the Jurassic of the United Kingdom.

1. Introduction

Pterosaurs were volant archosaurian reptiles of the Mesozoic, characterised by a flight membrane stretched between the fore and hind limbs that incorporated a hyper-extended fourth wing-finger composed of four elongate phalanges (Wellnhofer, 1991a; Unwin, 2005; Witton, 2013). In the largest Cretaceous forms such as Arambourgiania, Hatzegopteryx and Quetzalcoatlus, the total wingspan achieved lengths of 10.0 m or more (Martill et al., 1998; Buffetaut et al., 2003; Andres and Langston Jr, 2021), but Triassic and Jurassic forms were considerably smaller with typical wingspans of 0.5–2.0 m (Unwin, 2005; Witton, 2013; Benson et al., 2014; Jagielska et al., 2022). There is evidence that a few Jurassic forms reached large wingspans too, but they rarely exceeded 3 m (Smith et al., 2022.1; Jagielska et al., 2022).

By far the best-known pterosaurs of Jurassic age come from just three fossil Konservat Lagerstätten, two in southern Germany, the Lower Jurassic (Toarcian) Posidonia Shale (see Padian, 2008) and the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) plattenkalks (Arratia et al., 2015). In China, the Tiaojishan Formation and stratigraphical equivalents of Inner Mongolia, Hebei and Liaoning provinces comprise the third and are early Oxfordian in age (Wang et al., 2005.1). Pterodactyloids have only been reported rarely in the British Jurassic. Firstly, an isolated jaw from the Taynton Limestone Formation (Stonesfield slate) of Oxfordshire was referred to Ctenochamatidae by Buffetaut and Jeffery (2012), however, Andres et al. (2014.1) suggested that this specimen (OUM J.01419) was likely a crocodylomorph. Martill et al. (2022.2) referred an isolated tooth (NHMUK PV R 522.2) also from the Taynton Limestone Formation to Ctenochasmatidae.

1.1 Kimmeridge Clay Formation Pterosauria

Pterosaurs are rare in the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of England, but several occurrences have been documented, and at least two taxa are regarded as valid — Cuspicephalus scarfi and Rhamphorhynchus etchesi (Etches and Clarke, 2010; Martill and Etches, 2012.1; Martill and O'Sullivan, 2020). A third valid taxon — Normannognathus wellnhoferi is known from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation equivalents of Normandy, France (Buffetaut et al., 1998.1). Historically, several species of Pterodactylus were described in the 19th century (Owen, 1874; Lydekker, 1888), but these are undiagnosable and considered nomina dubia by Martill and O'Sullivan (2020). Presently, pterosaur remains from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation are referred to Rhamphorhynchinae, possibly Campylognathoididae and Monofenestrata, including Germanodactylidae and Darwinoptera (Martill and Etches, 2012.1; O'Sullivan and Martill, 2015.1; Witton et al., 2015.2; Martill and O'Sullivan, 2020).

2. Locality and geological context The new pterosaur specimen (EC K2576) was discovered in June 2022 in a gravel pit on the southern outskirts of Abingdon-on-Thames in Oxfordshire, where the Late Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay Formation was temporarily exposed in the floor of the quarry (Fig. 1). At the time of discovery, the aggregate (late Pleistocene sand and gravel from the proto-Thames: Corser, 1978) had been completely extracted, and the underlying Kimmeridge Clay was being excavated to install a sump, and to line the flanks of the pit to inhibit aquifer influx during backfilling.On the date of collection, the floor of the quarry sat on, and slightly above, a hardground surface in the clay characterised by a pebble bed containing sand and abundant phosphate pebbles (Fig. 2) including phosphatised fragments of ammonites of the genus Aulacostephanus sp., the bivalve species Nicaniella extensa (Phillips, 1829) and Myophorella swindonensis (Blake, 1880), lignite and pyrite-encrusted wood and occasional marine reptile bones, teeth and fish remains. Among these were ichthyosaur vertebrae, a crocodilian limb bone and vertebral centrum (likely Dakosaurus sp.), a pycnodont jaw and hybodont shark teeth. The phosphate pebble bed is interpreted to represent the Km7 sequence boundary and subsequent transgressive lag following the terminology of Taylor et al. (2001). This sequence boundary, recognised as a correlative conformity in the more distal basinward succession in Kimmeridge Bay, is known to be disconformable closer to the palaeo-shoreline of the London-Brabant massif. It is, therefore, not surprising to see a more marked stratigraphical expression of this surface at this location in Oxfordshire close to the western margin of the palaeo-landmass. Km7 coincides with the boundary between the autissiodorensis and elegans biozones and is a distinctive marker horizon that can be readily identified in the claystone succession. Fig. 1. Map showing locality of the newly discovered pterodactyloid pterosaur wing phalanx EC K2576 from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation.The pterosaur bone was found in disturbed clay ~ 300 mm above the pebble bed in claystones that contain distinctive Gravesia sp. and very abundant Pectinatites sp., ammonites that are diagnostic of the elegans biozone at the base of the Tithonian (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Frequent ichthyosaur remains also occur here, along with occasional plesiosaur and pliosaur remains. An early Tithonian age is consistent with the ubiquitous occurrence of Nanogyra virgula (Deshayes, 1831) which are known to become rare above the scitulus biozone (Martill et al., 2020.1) and Nanogyra nana (Sowerby, 1822) bivalves, which occur in lenticular limestones and other bivalve fauna. Further industrial excavation performed after the pterosaur specimen was collected exposed the older autissiodorensis biozone where ammonites were observed along with Laevaptychus aptychi, typical of the zone. On this basis, the new pterosaur specimen is considered to be Tithonian in age, and specifically from the elegans ammonite biozone (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).Fig. 2. Simplified stratigraphic log showing the interpreted stratigraphical position of the pterodactyloid pterosaur wing phalanx EC K2576 from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of Abingdon.

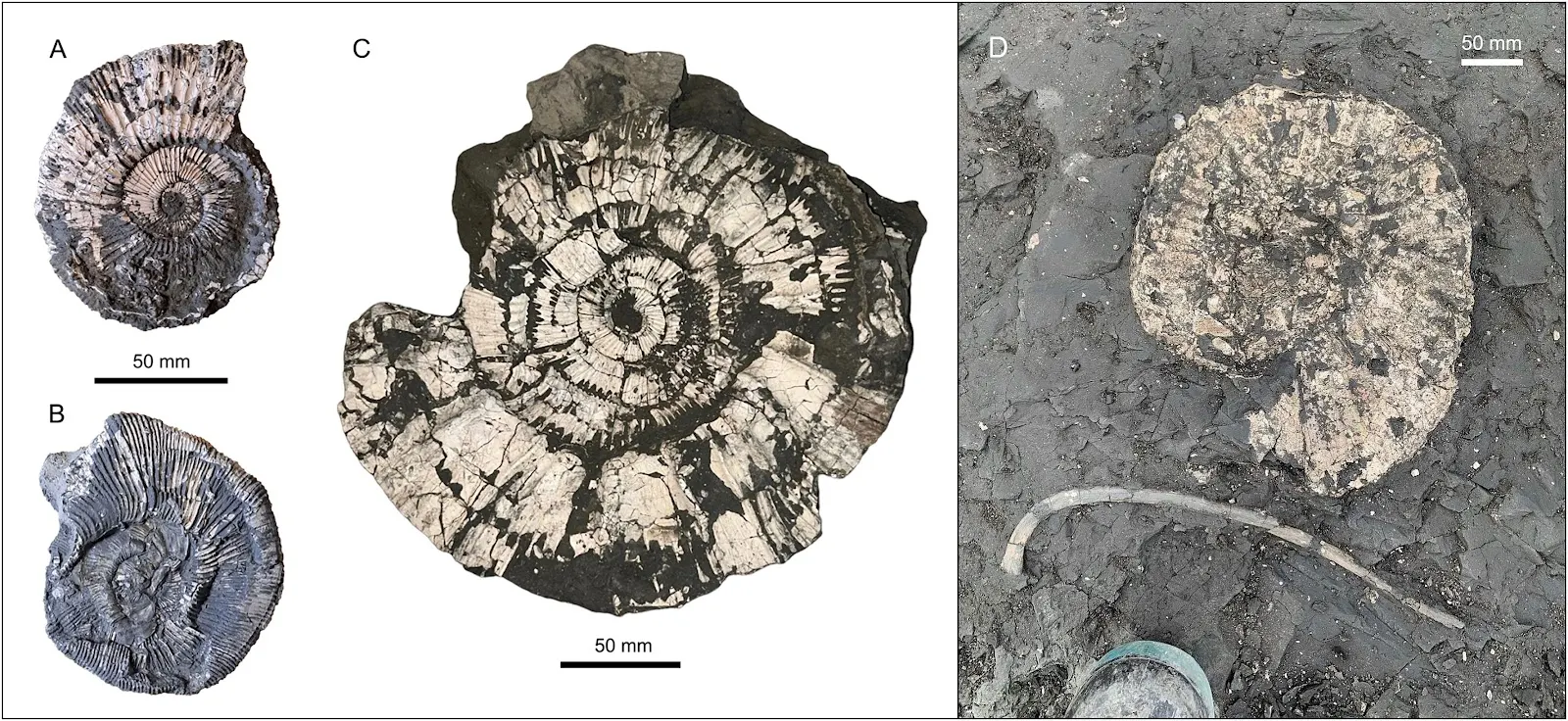

Fig. 1. Map showing locality of the newly discovered pterodactyloid pterosaur wing phalanx EC K2576 from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation.The pterosaur bone was found in disturbed clay ~ 300 mm above the pebble bed in claystones that contain distinctive Gravesia sp. and very abundant Pectinatites sp., ammonites that are diagnostic of the elegans biozone at the base of the Tithonian (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Frequent ichthyosaur remains also occur here, along with occasional plesiosaur and pliosaur remains. An early Tithonian age is consistent with the ubiquitous occurrence of Nanogyra virgula (Deshayes, 1831) which are known to become rare above the scitulus biozone (Martill et al., 2020.1) and Nanogyra nana (Sowerby, 1822) bivalves, which occur in lenticular limestones and other bivalve fauna. Further industrial excavation performed after the pterosaur specimen was collected exposed the older autissiodorensis biozone where ammonites were observed along with Laevaptychus aptychi, typical of the zone. On this basis, the new pterosaur specimen is considered to be Tithonian in age, and specifically from the elegans ammonite biozone (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).Fig. 2. Simplified stratigraphic log showing the interpreted stratigraphical position of the pterodactyloid pterosaur wing phalanx EC K2576 from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of Abingdon. Fig. 3. Stratigraphically relevant ammonites from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of the Abingdon pterosaur site. A, B, Pectinatites sp. male microconch preserved in pyrite with partial aragonite shell; C, Pectinatites sp. female macroconch preserved in cementstone nodule, with partial aragonite shell. Macroconch examples can get very large at this locality (up to 400 mm diameter in some cases); D, Gravesia sp. ammonite macroconch lying next to disarticulated ichthyosaur rib. The association of Gravesia and Pectinatites ammonites is diagnostic for an early Tithonian age. The pterodactyloid pterosaur EC K2576 specimen was collected from disturbed claystones at the same stratigraphic horizon < 10 m away from this Gravesia ammonite specimen, above the transgressive lag on the Km7 sequence boundary.

Fig. 3. Stratigraphically relevant ammonites from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of the Abingdon pterosaur site. A, B, Pectinatites sp. male microconch preserved in pyrite with partial aragonite shell; C, Pectinatites sp. female macroconch preserved in cementstone nodule, with partial aragonite shell. Macroconch examples can get very large at this locality (up to 400 mm diameter in some cases); D, Gravesia sp. ammonite macroconch lying next to disarticulated ichthyosaur rib. The association of Gravesia and Pectinatites ammonites is diagnostic for an early Tithonian age. The pterodactyloid pterosaur EC K2576 specimen was collected from disturbed claystones at the same stratigraphic horizon < 10 m away from this Gravesia ammonite specimen, above the transgressive lag on the Km7 sequence boundary. Fig. 4. Left wing phalanx 1 of a pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of Abingdon, Oxfordshire, EC K2576. A, original specimen; B, simplified interpretive drawing. Scale bar = 10 mm. Abbreviations: cfmc iv = cotyle for metacarpal IV; ext. tnd. proc = extensor tendon process; op = olecranon process; post gr. = posterior groove; pp = posterior process;

Fig. 4. Left wing phalanx 1 of a pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of Abingdon, Oxfordshire, EC K2576. A, original specimen; B, simplified interpretive drawing. Scale bar = 10 mm. Abbreviations: cfmc iv = cotyle for metacarpal IV; ext. tnd. proc = extensor tendon process; op = olecranon process; post gr. = posterior groove; pp = posterior process;

Etienne, James L.; Smith, Roy E.; Unwin, David M.; Smyth, Robert S.H.; Martill, David M.

A ‘giant’ pterodactyloid pterosaur from the British Jurassic Proceedings of the Geologists' Association (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2024.05.002

Copyright: © 2024 The authors / The Geologists' Association.

Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.