New evidence from West Papua offers fresh clues about how and when humans first moved into the Pacific

I realise I'm always writing about things that happened in the long pre-'Creation' period before creationists claim their god magicked the Universe up out of nothing, but there is so much of it. For Earth alone, 99.9975% of its history happened before it existed , if you believe what creationists claim.

The entire history of human evolution in Africa and dispersion into Eurasia, the Americas and the Pacific islands for example, happened before 'Creation Week', as did the transition from hunter-gatherer to settled agriculture and urbanisation.

In fact, it wasn't until humans began to form proto-nation states in the form of waring petty kingdoms led by violent warlords once they had established agriculture and needed to defend their land against other tribes, that they started to invent origin myths to both explain how they got there and to justify their ownership, and probably genocides against former occupiers.

When these tales got written down and bound up into a book decreed by priests to be the inerrant word of their creator god, we got the beginnings of the holy books that some uneducated people today still believe are real science and real history.

But of course, we now know those who made up the origin myths knew nothing outside their tiny fragment of the planet and tiny fragment of time. They would have had no inkling that there were people moving into far away islands in oceans of which they knew nothing, like those in the Pacific, the evidence for which is being revealed by archaeologists and anthropologists using modern scientific methods.

For example, a team led by Dylan Gaffney, an associate professor of Palaeolithic Archaeology at the University of Oxford and Daud Aris Tanudirjo of the Departemen Arkeologi, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia have just published evidence that early Homo sapiens were populating the Pacific islands between 50,000 and 55,000 years ago. This evidence was found in Western Papua.

Their findings are published today in the Cambridge University Press journal Antiquity and is the subject of an article in The Conversation. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

New evidence from West Papua offers fresh clues about how and when humans first moved into the Pacific

Tristan Russell/Raja Ampat Archaeological Project, Author provided

In the deep human past, highly skilled seafarers made daring crossings from Asia to the Pacific Islands. It was a migration of global importance that shaped the distribution of our species – Homo sapiens – across the planet.

These mariners became the ancestors of people who live in the region today, from West Papua to Aotearoa New Zealand.

For archaeologists, however, the precise timing, location and nature of these maritime dispersals have been unclear.

For the first time, our new research provides direct evidence that seafarers travelled along the equator to reach islands off the coast of West Papua more than 50 millennia ago.

Digging at the gateway to the Pacific

Our archaeological fieldwork on Waigeo Island in the Raja Ampat archipelago of West Papua represents the first major international collaboration of its kind, involving academics from New Zealand, West Papua, Indonesia and beyond.

We focused our excavations at Mololo Cave, a colossal limestone chamber surrounded by tropical rainforest. It stretches a hundred metres deep and is home to bat colonies, monitor lizards and the occasional snake.

In the local Ambel language, Mololo means the place where the currents come together, fittingly named for the choppy waters and large whirlpools in the nearby straits.

Archaeologists Daud Tanudirjo and Moses Dailom excavating at Mololo Cave.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

These archaeological findings were rare in the deepest layers, but radiocarbon dating at the University of Oxford and the University of Waikato demonstrated humans were living at Mololo by at least 55,000 years before the present day.

Foraging in the rainforest

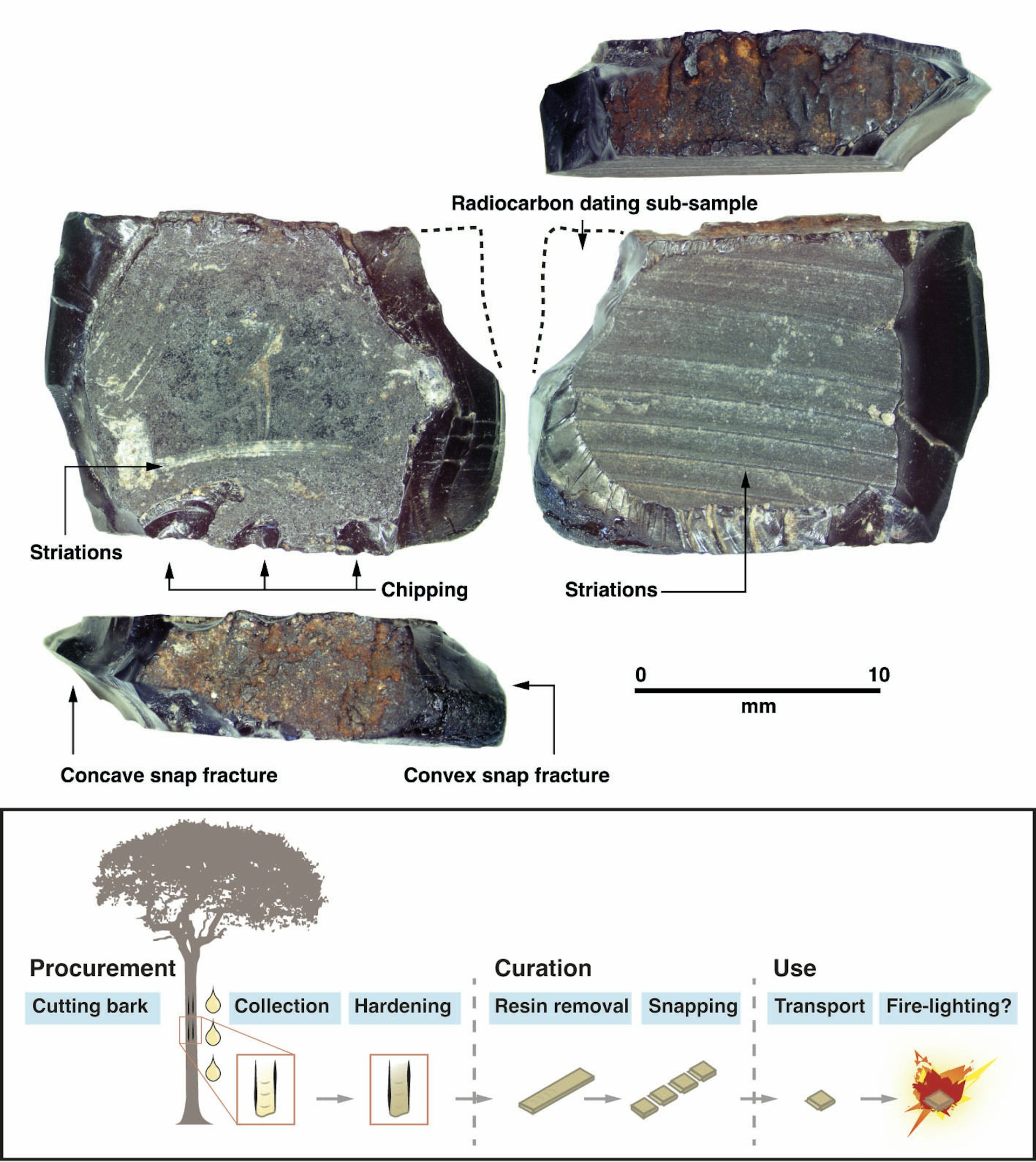

A key finding of the excavation was a tree resin artefact that was made at this time. This is the earliest example of resin being used by people outside of Africa. It points to the complex skills humans developed to live in rainforests.

Scanning-electron microscope analysis indicated the artefact was produced in multiple stages. First the bark of a resin-producing tree was cut and the resin was allowed to drip down the trunk and harden. Then the hardened resin was snapped into shape.

The function of the artefact is unknown, but it may have been used as a fuel source for fires inside the cave. Similar resin was collected during the 20th century around West Papua and used for fires before gas and electric lighting was introduced.

The tree resin artefact found at Mololo Cave dates back to 55,000 to 50,000 years ago. The chart shows how it may have been made and used.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

A modern example of tree resin from the Raja Ampat Islands being used for starting a fire.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

The Mololo excavation helps us to clarify the precise time humans moved into the Pacific. This timing is hotly debated because it has major implications for how rapidly our species dispersed out of Africa to Asia and Oceania.

It also has implications for whether people drove Oceanic megafauna like giant kangaroos (Protemnodon) and giant wombats (Diprotodontids) to extinction, and how they interacted with other species of hominins like the “hobbit” (Homo floresiensis) that lived on the islands of Indonesia until about 50,000 years ago.

Archaeologists have proposed two hypothetical seafaring corridors leading into the Pacific: a southern route into Australia and a northern route into West Papua.

In what is today northern Australia, excavations indicate humans may have settled the ancient continent of Sahul, which connected West Papua to Australia, by 65,000 years ago.

However, findings from Timor suggest people were moving along the southern route only 44,000 years ago. Our work supports the idea that the earliest seafarers crossed instead along the northern route into West Papua, later moving down into Australia.

Two possible seafaring pathways from Asia to the Pacific region: a northern route along the equator to Raja Ampat and a southern route via Timor to Australia.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

Despite our research, we still know very little about the deep human past in West Papua. Research has been limited primarily because of the political and social crisis in the region.

Importantly, our research shows early West Papuans were sophisticated, highly mobile and able to devise creative solutions to living on small tropical islands. Ongoing excavations by our project aim to provide further information about how people adapted to climatic and environmental changes in the region.

Hand stencils of unknown age from the Raja Ampat Islands.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

It was not until about 3,000 years ago that seafarers pushed out beyond the Solomon Islands to settle the smaller islands of Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. Their descendants later voyaged as far as Hawaii, Rapa Nui and Aotearoa.

Charting the archaeology of West Papua is vital because it helps us understand where the ancestors of the wider Pacific came from and how they adapted to living in this new and unfamiliar sea of islands.

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Abdul Razak Macap, a social anthropologist at the Regional Cultural Heritage Center in Manokwari.

Dylan Gaffney, Associate Professor of Palaeolithic Archaeology, University of Oxford and Daud Aris Tanudirjo, Pengajar (Lektor Kepala) di Departemen Arkeologi, Universitas Gadjah Mada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AbstractThe standard creationists’ response to any evidence that Earth is older than 10,000 years is to misrepresent the dating methods the archaeologists used. By an amazing coincidence, it always turns out that the (unspecified) mistake they made just happened to make, as in this case, 10,000 years or less look like 50,000 years. In other cases, it amazingly makes 10,000 years look like 150 million, or 65 million or whatever creationists need to claim the mistake made it look like.

The dynamics of our species’ dispersal into the Pacific remains intensely debated. The authors present archaeological investigations in the Raja Ampat Islands, north-west of New Guinea, that provide the earliest known evidence for humans arriving in the Pacific more than 55 000–50 000 years ago. Seafaring simulations demonstrate that a northern equatorial route into New Guinea via the Raja Ampat Islands was a viable dispersal corridor to Sahul at this time. Analysis of faunal remains and a resin artefact further indicates that exploitation of both rainforest and marine resources, rather than a purely maritime specialisation, was important for the adaptive success of Pacific peoples.

Introduction

When Homo sapiens dispersed from Eurasia to the Pacific they moved through the islands of Wallacea to reach Sahul (the Pleistocene continent connecting New Guinea with Australia) (Figure 1). To facilitate these journeys, humans devised seafaring technologies and crossed several biogeographic thresholds, pushing beyond the Afro-Eurasian landmass for the first time into increasingly small and faunally depauperate islands (O'Connell & Allen 2015; Shipton et al. 2021). These dispersals encouraged major behavioural adaptations—not seen among other hominin species such as Homo erectus, Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis—as our species learned to live among, and transform, these tropical islands (O'Connor et al. 2017; Gaffney 2022). The timing and route of these movements remain unresolved and highly contested (Kealy et al. 2018; Norman et al. 2018.1; Bird et al. 2019; Bradshaw et al. 2019.1; Allen & O'Connell 2020).

Archaeological evidence from Madjedbebe, a rockshelter in Arnhem Land, northern Australia, suggests that humans initially arrived in Sahul via a southern route that included the Lesser Sunda Islands, around 65–60ka (thousand years ago) (Clarkson et al. 2017.1). Along the southern route, evidence of H. sapiens at Liang Bua (Flores Island), Makpan (Alor) and Laili, Asitau Kuru and Lene Hara (Timor), however, stands at maximally 44ka (Hawkins et al. 2017.2; Sutikna et al. 2018.2; Shipton et al. 2019.2; Kealy et al. 2020.1). This disparity has led some archaeologists to argue that the northern Australian dates are erroneous and that a later arrival to Sahul after 50ka, also involving a northern equatorial route, is more convincing (O'Connell et al. 2018.3). Although cave art from the Maros Karst sites (Sulawesi) (Brumm et al. 2021.1) and Lubang Jeriji Saléh (Borneo) (Aubert et al. 2018.4) include figurative hunting scenes that date to at least 45ka, the earliest sites along the small islands of the northern island chain—Golo (Gebe Island), Liang Lemdubu (Aru Islands) and Liang Sarru (Talaud Islands)—date to less than 40ka (Tanudirjo 2001; O'Connor et al. 2005; Bellwood et al. 2019.3a). Determining the nature of H. sapiens migrations to the Pacific is crucial for understanding how our species diversified outside of Africa, adapted to the challenges and opportunities of these novel environments, including insularity and tropical forest cover, and interacted with other hominin species present in the region. Northern dispersals may have brought H. sapiens into close contact with Denisovan hominins, perhaps present around Sulawesi (Carlhoff et al. 2021.2), or Homo luzonensis in the Philippines (Détroit et al. 2019.4), while southern movements may have seen our species cohabit islands, however briefly, with Homo floresiensis (Sutikna et al. 2016).Figure 1. Northern and southern routes through Wallacea, showing Mololo Cave on Waitanta. Inset A) seafaring simulations and chance of successful landing on Waitanta from nearby landmasses, based on averages taken from 1.5kt paddling at -30m and -50m sea levels (Table S6); Inset B) Waitanta shoreline and Mololo Cave at 50 000 years ago and at the Last Glacial Maximum (20 000 years ago) based on multibeam and GEBCO bathymetry data (figure by authors).

Here, we report the first excavations from the Raja Ampat Islands, off the north-west coast of New Guinea, a key island group along the ‘northern route’ to Sahul. We first provide bathymetric (ocean floor depth) reconstructions of island size and voyage simulations for the northern entry to Sahul, and then detail excavations, radiometric dating and multidisciplinary archaeological and palaeoecological analyses at the site of Mololo Cave on Waigeo Island to clarify when and how humans moved along the northern route into Sahul, prior to 50ka.

Coastline reconstruction and seafaring modelling

From 65–50ka, eustatic sea level fluctuated between approximately 30–50m below present levels (Kealy et al. 2017.3). Multibeam imagery demonstrates that Waigeo and Batanta islands were, at times, connected by a shallow platform (Figures 1B & S1, see also online supplementary material (OSM)). We call this palaeo-island Waitanta (wai = water, tanta = that extends in front of your eyes). This island was separated from Sahul by the deep Sagewin Strait throughout the Pleistocene, even during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). As such, humans would have needed watercraft to move between Waitanta and Sahul. At 50ka, the Sagewin Strait was 5–6km wide on average and 2.5km at its minimal distance, and at the LGM the average width was about 5km with a minimal crossing distance of 1.5km.

Our novel seafaring simulations show that eastward-moving crossings were most easily achieved between Obi–Kofiau–Waitanta, even with minimal propulsion (Figures 1A & S2, Tables S1–S9, see OSM for simulation methods and results). Successful arrivals on Waitanta by paddling at 1.5kt (0.77m/s) were nearly guaranteed when moving from Kofiau, Gebe and Halmahera in the west or Sahul in the east. Trips from Sahul would be quickest, followed by Gebe, Kofiau and Halmahera, lasting 2–3 days. Crossings from Talaud and Morotai to the north were highly unlikely. Even in suboptimal weather, movements between Waitanta and Sahul across the Sagewin Strait were safe for rafts paddled at 1.5kt but were also possible with slower paddling during ideal conditions (Table S10).

Mololo Cave excavations and chronostratigraphy

Mololo Cave (0°18′21.0″S, 130°55′01.4″E; Raja Ampat Archaeological Project site code: WAI-1) lies within the Rabia Strait, leading into Waigeo Island's Mayalibit Bay (Figures 2A & S3, see also OSM). A transect across Rabia Strait indicates it is maximally 46m deep and would have been a valley system during the Pleistocene, becoming inundated with seawater after c. 9.5ka; at 50ka, Mololo was located about 15km inland. Formed from Miocene limestone, Mololo includes an outer chamber, exposed to daylight owing to roof collapse, and a dark inner chamber, home to several bat colonies (Figure 2). A 1 × 1m test pit had been excavated by the Centre for Papuan Archaeology near the cave entrance to 0.8m deep in 2012. Excavations in 2018–2019, reported here, targeted three parts of the cave system: Area 1 near the cave entrance; Area 2 on a flat, elevated space in the outer chamber; and Area 3 at the edge of the inner chamber.

Trench 1 was excavated to a depth of 2.57m (Figure 3A, Table S11). The upper stratigraphy consists of interleaved clays, midden material and fire ash, indicating recurring frequentation between c. 15 and 2.1ka (Figure 4, Table S12). In three instances, charcoal with a Holocene age underlies terminal Pleistocene strata, possibly associated with bioturbation or disturbance during the production of hearths and large bone middens. Below this is undisturbed, indurated guano, likely deposited by small bats roosting on the roof above the area where the trench is located. Charcoal incorporated within one indurated context dates to c. 44–43ka, but it is unclear if it is anthropogenic. Owing to its small size, the charcoal was prepared with acid/base/acid rather than acid-base-oxidation, a pre-treatment that can produce younger-than-actual dates for material over about 20ka (Higham et al. 2009). As such, 43ka is likely a minimum possible age for these indurated contexts. They overlie looser guano associated with numerous small bat bones that could not be radiocarbon dated owing to poor collagen preservation (Table S13). At the base of the excavation, uranium-series dating indicates that sedimentary calcite encrusted on limestone bedrock dates to 51ka, and coral gravel (Porites sp.) overlying the bedrock dates to 125ka (Marine Isotope Stage 5e, the last interglacial) and 200ka (Marine Isotope Stage 7). This indicates Area 1 was originally submerged and has been subsequently uplifted to its present location (Table S14).Figure 2. Mololo Cave system showing excavation units. Inset A) location of Mololo Cave at the entrance to Mayalibit Bay. Inset B) transect of entrance to Mololo Cave, relative to mean sea level (MSL) (figure by authors).

[…]

Discussion

The Mololo investigations provide critical, albeit sparse, evidence for occupation along the northern equatorial route to Sahul before 50ka (possibly >55ka). H. sapiens probably produced this archaeological record, moving by raft/boat through the humid tropics. However, it should be noted that based on modern population genetic evidence (Jacobs et al. 2019.5) it is not currently possible to exclude the possibility that Denisovans or people who carried both H. sapiens and Denisovan ancestry—having admixed in the islands of Wallacea or continental Eurasia—migrated along this route.

[…]

Conclusion

Multi-proxy archaeological and palaeoecological analyses of the Mololo Cave sequence on the palaeo-island of Waitanta provide evidence for the earliest known peopling of the Pacific region >55 000–50 000 years ago. These humans practised complex plant processing and engaged with both coastal and tropical forest ecologies. The Raja Ampat archaeological record provides some of the earliest global evidence for humans exploring rainforests outside Africa and the earliest evidence of our species using small islands. Capacities for adaptive flexibility and environmental transformation likely stimulated human movements into insular rainforests, previously beyond the range of other hominin species. These settings help us to understand the process of cultural and biological diversification generated as our species dispersed around the planet and began to push the boundaries of novel habitats, and how humans have become enmeshed in these ecologies for tens of millennia.

Gaffney D, Tanudirjo DA, Djami ENI, et al.

Human dispersal and plant processing in the Pacific 55 000–50 000 years ago. Antiquity. Published online 2024:1-20. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.83

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of Antiquity Publications Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

The other response is to claim, again with no evidence whatsoever, that radioactive decay rates were very much greater in those days, and again by an order of magnitude sufficient to make 10,000 years or less look like whatever a creationist needs, to dismiss the evidence. And, magically, even with a decay rate that would have made the formation of atoms impossible because of the weaker nuclear forces, their magic creator still managed to create living organisms, presumably leaving the atoms to appear later when decay rates had fallen enough. And of course, by another amazing coincidence, those decay rates just happened to stabilise at today's rates when we developed the ability to measure them.

If creationists were any less ignorant of the science they lie about, it would be far less easy for their cult leaders to fool them with this ludicrously implausible misrepresentation of basic science. The frauds obviously know their simple-minded marks well.

What Makes You So Special? From The Big Bang To You

How did you come to be here, now? This books takes you from the Big Bang to the evolution of modern humans and the history of human cultures, showing that science is an adventure of discovery and a source of limitless wonder, giving us richer and more rewarding appreciation of the phenomenal privilege of merely being alive and able to begin to understand it all.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

Ten Reasons To Lose Faith: And Why You Are Better Off Without It

This book explains why faith is a fallacy and serves no useful purpose other than providing an excuse for pretending to know things that are unknown. It also explains how losing faith liberates former sufferers from fear, delusion and the control of others, freeing them to see the world in a different light, to recognise the injustices that religions cause and to accept people for who they are, not which group they happened to be born in. A society based on atheist, Humanist principles would be a less divided, more inclusive, more peaceful society and one more appreciative of the one opportunity that life gives us to enjoy and wonder at the world we live in.

Available in Hardcover, Paperback or ebook for Kindle

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.