A survey published a few days ago shows how people of faith are taking their information about the efficacy and safety of the anti-covid vaccines not from science but from their cult's leadership.

The same survey also confirms the findings of other polls that those least concerned about the welfare of other people, even those in their own community, are the white evangelical Christians - the very same people who are most likely to:

- Support Donald Trump.

- Support white supremacist organizations.

- Be right-leaning Repugnicans.

- Be Creationists.

- Oppose restrictions on gun ownership.

- Be pro-life, anti-choice, mysogynists.

- Believe the ludicrous, pro-Trump, antisemitic, Dominionist QAnon conspiracy hoax.

- Believe that Trump won the 2020 election by a landslide.

- Think Earth is just a few thousand years old and probably flat, with the sun orbiting it.

Executive Summary

As the U.S. navigates evolving dynamics related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and access, there has been a dearth of hard data to understand the cultural dynamics of this problem, and even less rigorous data available to understand how faith-based interventions might mitigate vaccine hesitancy and resistance. The PRRI–IFYC Religion and the Vaccine Survey, the largest study conducted to date in this area, reveals that faith-based approaches supporting vaccine uptake can influence members of key hesitant groups to get vaccinated and thus can be a vital tool for the public health community as we work toward herd immunity.

Faith-based approaches are influential among vaccine hesitant communities. More than one in four (26%) Americans who are hesitant to get a COVID-19 vaccine, and even 8% of those who are resistant to getting a vaccine, report that at least one of six faith-based approaches supporting vaccinations would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

- Among those who attend religious services at least a few times per year, 44% of those who are hesitant and 14% of those who are resistant say faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

- Among white evangelical Protestants who are vaccine hesitant, nearly half (47%) who regularly attend services say faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

- Approximately one-third of Black Protestants (36%) and Hispanic Americans (33%) who are vaccine hesitant say one or more faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

- 26% of Republicans and 24% of rural Americans who are vaccine hesitant say faith-based approaches would improve their likelihood of getting vaccinated.

- Notably, three in ten (30%) of those who are very worried about the safety of vaccines and are vaccine hesitant say that faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

These faith-based approaches include: A religious leader encouraging vaccine acceptance, a religious leader getting a vaccine, religious communities holding information forums, learning that a fellow religious community member received a vaccine, a nearby religious congregation serving as a vaccination site, and religious communities providing vaccine appointment assistance.

The positive influence of faith-based approaches on vaccine uptake is particularly important among Protestant Christians, who have higher rates of vaccine hesitancy and refusal.

- Hispanic Protestants are particularly likely to be vaccine hesitant (42%), and an additional 15% do not plan to get vaccinated.

- Nearly three in ten white evangelical Protestants (28%) are vaccine hesitant, and an additional one in four (26%) say they will not get vaccinated.

- Black Protestants are similarly divided, with 32% hesitant and 19% refusing to get vaccinated.

Church attendance is currently playing a different role in vaccine uptake among Black Protestants and white evangelical Protestants.

- Among Black Protestants, attending religious services is positively correlated with vaccine acceptance. Nearly six in ten (57%) of those who attend services at least a few times per year are vaccine accepters, compared to 41% among those who do not attend services. Faith-based interventions here can increase momentum already evident on the ground.

- By contrast, among white evangelical Protestants, only 43% of those who attend religious services frequently are vaccine accepters, compared to 48% of those who attend less frequently. In this case, faith-based interventions have untapped potential to shift these dynamics.

There are clear opportunities for religious leaders to intervene to encourage vaccination.

- Among those hesitant to get a vaccine, 70% of Black Protestants and 66% of white evangelical Protestants would turn to a religious leader at least a little for information about vaccination.

- Additionally, 53% of Hispanic Catholics, 43% of white Catholics, 36% of white mainline Protestants, and even 21% of religiously unaffiliated Americans would turn to a religious leader at least a little for information about vaccination.

Belief in conspiracy theories is related to vaccine hesitancy, but faith-based approaches can help.

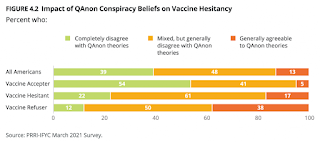

- Americans who are vaccine accepters are less likely to agree with QAnon conspiracy theories (5%) than those who are vaccine hesitant (17%) or refusers (38%).

- Importantly, faith-based interventions could be a way to reach conspiracy theory believers: More than one-third (36%) of those who are hesitant and agree with QAnon theories indicate that faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

Education levels and age are sources of division around vaccine uptake. Americans with four-year college degrees or more are consistently more likely than those without a four-year degree to be vaccine accepters; when it comes to age, Americans ages 65 and older are much more likely to be vaccine accepters.

- The impact is particularly pronounced among Americans who identify with two or more racial or ethnic identities (multiracial). Three in four multiracial Americans (75%) with four-year degrees are vaccine accepters, compared to 39% of those without a four-year degree.

- The educational divide on vaccine acceptance is also large among Black Americans (66% with a four-year degree, 40% without), Hispanic Americans (66% with a four-year degree, 49% without), and white Americans (77% with a four-year degree, 52% without).

- Hesitancy is more pronounced among younger Americans, with less than half of Americans under age 50 (48%) reporting they have received a vaccine or will do so as soon as possible, compared to 58% of those ages 50–64 and 79% of those ages 65 and older. More than six in ten Americans ages 18–29 (62%), ages 30–49 (68%), and ages 50–64 (64%) expressed at least moderate concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines, while only 47% of those over age 65 reported similar concerns.

Beyond Fox News, the rise of far-right media outlets dramatically affect vaccine hesitancy among Republicans. As many surveys have shown, Republicans (45%) are less likely than independents (58%) and Democrats (73%) to be vaccine accepters, but Republican attitudes are strongly influenced by television news consumption.

- Majorities of Republicans who report trusting mainstream news (58%) or Fox News (54%) most are vaccine accepters.

- By contrast, only about three in ten Republicans who trust far-right news (32%) or no television news (30%) are vaccine accepters.

Vaccine Accepters, Hesitant, and Refusers

As of the end of March, 32% of Americans reported having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nearly six in ten (59%) report that a family member has received at least one dose of a vaccine, 39% report that a close friend has received a vaccine, and 36% say they have an acquaintance who has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Only 12% of Americans reported at the time of the survey that they did not know anyone who had received at least one dose of a vaccine.

An additional 26% of Americans say they will get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available to them, for a total of 58% who have either gotten at least one dose of a vaccine or will get vaccinated as soon as possible.[1] Another 28% of Americans are hesitant, including 19% who say they will wait and see how the vaccines are working for others and 9% who will only get vaccinated if required to for work, school, or other activities. Vaccine refusers—those who say they will definitely not get a vaccine—comprise 14% of Americans.

Among partisans, nearly three in four Democrats (73%) are vaccine accepters who either say that they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine or they will get vaccinated as soon as possible. An additional 21% of Democrats are in the hesitant category, with 15% who want to wait and see how it works for others and 6% who will only get it if required. Only 6% of Democrats are vaccine refusers. A majority of independents (58%) either have received at least one dose of a vaccine or will get vaccinated as soon as possible. Nearly three in ten are hesitant (29%), with 20% who want to wait and see, 9% who will only get vaccinated if required, and 13% who say they will refuse vaccination. Less than half of Republicans (45%) say they have received a dose or will get vaccinated as soon as possible. Nearly one-third of Republicans (32%) are hesitant, including 20% who say they will wait and see and 12% who say they will only get vaccinated if required. Notably, nearly one in four Republicans (23%) say they will not get a COVID-19 vaccine.

Republicans are significantly divided by their news sources. Majorities of Republicans who report most trusting mainstream television news sources (broadcast networks, local news, and public television, 58%) or Fox News (54%), are vaccine accepters. By contrast, only about three in ten of those who most trust far-right news sources, such as Newsmax or One America News Network (OANN, 32%) or do not use television news as a source (30%) are vaccine accepters; each of these groups has roughly equal proportions who are vaccine refusers (31% and 36%, respectively). Notably, there are no similar gaps in vaccine acceptance by trusted news source among Democrats and independents.

Religious Affiliation and Vaccine Hesitancy

Jewish Americans (85%) are by far the most likely to be vaccine accepters, to have received a vaccine, or to say they will get vaccinated as soon as possible. More than two-thirds of white Catholics (68%) are vaccine accepters, as are 64% of other Christians, 63% of white mainline Protestants, and 63% of other non-Christian religious Americans.[2] Majorities of religiously unaffiliated Americans (60%) and Hispanic Catholics (56%), as well as half of Mormons (50%), are also vaccine accepters. Less than half of Black Protestants (49%), other Protestants of color (45%), white evangelical Protestants (45%), and Hispanic Protestants (43%) say they have gotten or will get vaccinated as soon as possible.[3]

Among the religious groups least receptive to the vaccines, white evangelical Protestants stand out as the most likely to say they will refuse to get vaccinated (26%), with an additional 28% who are hesitant. About one in five other Protestants of color (20%), Black Protestants (19%), and Mormons (17%) say they will not get vaccinated, and another one-third of each are hesitant (35%, 32%, and 33%, respectively). Among these less receptive religious groups, Hispanic Protestants are less likely to say they will not get vaccinated (15%) but more likely than any other religious group to be vaccine hesitant (42%).

Frequency of church attendance has different impacts on vaccine acceptance across different religious groups. It has little impact among white Catholics. More frequent church attendance is correlated with lower likelihood of vaccine hesitancy among white mainline Protestants and black Protestants, but it is associated with higher vaccine hesitancy among white evangelical Protestants. White mainline Protestants who attend religious services at least a few times per year are less likely than those who seldom or never attend to be vaccine hesitant (19% vs. 26%). Black Protestants who attend religious services at least a few times a year are significantly less likely than those who seldom or never attend to be in the vaccine hesitant (28% vs. 36%) or refuser (15% vs. 23%) categories.[4] By contrast, white evangelical Protestants who more frequently attend religious services are more likely than those who seldom or never attend to be vaccine hesitant (31% vs. 24%), although they are not more likely to be vaccine refusers (26% vs. 27%).[5]

Demographics and Vaccine Hesitancy

White Americans (60%) and Americans of other races (66%) are more likely than Hispanic Americans (52%), multiracial Americans (50%), and Black Americans (46%) to have received a vaccine or say they will get vaccinated as soon as possible.[6] Hispanic (37%) and Black (34%) Americans are most likely to be vaccine hesitant, to say they will wait and see how the vaccines work, or to only get vaccinated if required, while 29% of multiracial Americans, 26% of Americans of other races, and 25% of white Americans fall into this category. Multiracial (21%) and Black (19%) Americans are most likely to be refusers, saying they will not get vaccinated, compared to 15% of white Americans, 11% of Hispanic Americans, and 8% of Americans of other races.

Americans with more formal education are more likely to be willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Among those who have postgraduate degrees, 79% have gotten or will get a vaccine as soon as possible, 16% are hesitant, and only 5% will not get vaccinated. Those with four-year college degrees are similar: 70% are accepters, 21% are hesitant, and 8% will not get vaccinated. Americans with some college but not a four-year degree are less likely to have gotten or be willing to get vaccinated right away (56%), and more likely to be hesitant (30%) or refuse vaccination altogether (14%). Less than half of those with high school education or less (45%) are vaccine accepters; a majority are either hesitant (33%) or refusers (21%).

Education gaps persist across all race and ethnic groups. White Americans with at least a four-year college degree (7%) are less likely than those without four-year college degrees (18%) to say they will not get a COVID-19 vaccine. The same is true of Black Americans (9% vs. 22%), multiracial Americans (8% vs. 27%), and Americans of other races (3% vs. 16%). The education gap is narrower among Hispanic Americans (8% vs. 12%), although Hispanic Americans without four-year degrees are more likely than those with four-year degrees to be hesitant (39% vs. 26%).

Younger Americans are more likely than older Americans to be hesitant or say they will not get a COVID-19 vaccine. Among those ages 65 and older, 79% are vaccine accepters, saying they have either received a dose of a vaccine or will get it as soon as possible, 13% are hesitant, reporting they will wait and see or only get vaccinated if required, and 7% are rejecters, saying they will not get a vaccine. A majority of Americans ages 50–64 (58%) are vaccine accepters, but the proportions of hesitant (27%) and refusers (14%) are twice that of the older age group. Both age groups under 50 are less likely to be vaccine accepters: 48% of those ages 30–49 and 49% of those ages 18–29 have received a dose or will get vaccinated as soon as possible. About one-third of each group is hesitant (35% of those ages 30–49 and 33% of those ages 18–29), and 17% of those ages 30–49 and 18% of those ages 18–29 indicate they will not get vaccinated.

Men (61%) are more likely than women (54%) to have gotten a dose of a vaccine or to say they will get one as soon as possible, and slightly less likely than women to say they are hesitant (26% vs. 30%). However, similar proportions of men (13%) and women (15%) say they will not get vaccinated.

Americans living in urban and suburban areas are more willing to get vaccines than those in rural areas. About six in ten urban (60%) and suburban (59%) Americans say they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine or will get vaccinated as soon as possible, 28% of each group are hesitant, and 11% of urban and 13% of suburban Americans say they will not get vaccinated. By contrast, 46% of rural Americans are vaccine accepters, 30% are hesitant, and about one in four (24%) say they will not get it at all.

Experiences With COVID-19 and Vaccine Hesitancy

Overall, reported experiences with economic or health impacts of COVID-19 have only small effects on vaccine willingness. For example, among those who have lost jobs due to the pandemic, 17% are refusers and 32% are hesitant, compared to 14% and 27% among those who have not lost jobs. Among those who know someone who has died of COVID-19, 11% are refusers and 26% are hesitant, compared to 16% and 29% among those who do not know someone who has died of COVID-19.

However, Americans who are worried about themselves or someone in their family getting sick with COVID-19 in the future are more likely to be willing to get the vaccine. Approximately six in ten Americans are either very worried (23%) or somewhat worried (39%) that they or a loved one will become ill with COVID-19, compared to about four in ten who say they are not too worried (27%) or not at all worried (11%) about the virus. Among those who are at least somewhat worried, 61% are vaccine accepters, 29% are hesitant, and 10% are refusers. Among those who are not too worried about getting sick or someone in their family getting sick, 55% are vaccine accepters, 29% are hesitant, and 16% are refusers. Those who are not at all worried they or someone in their family will get sick with COVID-19 are significantly less likely to be vaccine accepters: 42% say they have gotten or will get vaccinated as soon as possible, 21% are hesitant, and more than one-third (36%) say they will not get vaccinated.

Faith-Based Approaches Could Persuade the Vaccine Hesitant and Refusers

Among Americans who are hesitant about getting a vaccine, approximately one in four (26%) indicate that one or more faith-based approaches would make them at least somewhat more likely to get vaccinated. Even among vaccine rejecters, 6% say one or more faith-based approaches might sway them.

The individual faith-based scenarios explored in the survey and their impact on improving vaccine uptake are summarized in Table 1.6.

In the general population, these faith-based approaches are less powerful than the influences of close friends, family members, or trusted health care providers. For example, 40% of those who are hesitant say a close friend or family member getting a vaccine would make them more likely to get a vaccine, compared to 7% of refusers. Four in ten of those who are hesitant (40%) also say a doctor or health care provider getting a vaccine would make them more likely to get a vaccine, compared to 9% of refusers.

But among populations with strong attachments to religion, faith-based approaches rival the effects of family members and health care providers. Among those who attend religious services at least occasionally and are vaccine hesitant, 44% would be somewhat or much more likely to get vaccinated with one or more of these faith-based approaches, as would 14% of vaccine refusers who regularly attend religious services. The impact is smaller among those who seldom or never attend religious services: 18% of this group who are vaccine hesitant indicate one or more of the religious scenarios would make them more likely to get vaccinated, along with 4% of this group who are vaccine refusers.

Religious groups with high levels of vaccine hesitancy or refusal are among the most attracted by these faith-based approaches. Nearly four in ten white evangelical Protestants who are hesitant to get vaccinated (38%) say that one or more of these faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get a vaccine. That proportion increases to nearly half (47%) among vaccine hesitant white evangelical Protestants who attend religious services at least a few times a year. More than one-third of Black Protestants who are vaccine hesitant (36%) and one-third of Hispanic Catholics who are vaccine hesitant (33%) also indicate that faith-based approaches could improve their likelihood of getting a vaccine.[7]

Smaller proportions of vaccine hesitant white mainline Protestants (18%) and white Catholics (15%) say one or more of the faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get a vaccine. For white mainline Protestants, but not for Catholics, the proportion saying these interventions would be effective increases among those who attend religious services (30% of white mainline Protestants).[8]

Notably, faith-based approaches to vaccine uptake also have a significant effect on a number of non-religious groups that have significant levels of vaccine hesitancy. Among Republicans, 26% of those who are vaccine hesitant and 7% of those who are vaccine resistant report that faith-based interventions would make them more likely to get vaccinated. Similarly, among rural Americans, 24% of those who are vaccine hesitant and 5% of those who are vaccine resistant say faith-based approaches would have a positive influence on their likelihood of getting vaccinated. And even among younger Americans under age 50, who are less likely than older Americans to attend religious services, 25% of those who are vaccine hesitant and 8% of those who are refusers nonetheless say that faith-based approaches would make them more likely to receive a vaccine.

Vaccine Worries

Between 40% and 60% of Americans are at least somewhat worried about various potential complications from COVID-19 vaccines. A majority of Americans (58%) are worried that the long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccines are unknown. About half of Americans are at least somewhat worried that they will experience serious side effects from the vaccines (49%), that the vaccines are not as safe as they are said to be (45%), or that the vaccines are not as effective as they are said to be (43%).

A four-point composite index was created to evaluate Americans’ concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, including the four areas of concern listed above. Each question was combined using an additive scale that was then converted into a four-point scale where a score of 1 indicates major concerns, 2 indicates moderate concerns, 3 indicates few concerns, and 4 indicates very few concerns about the vaccines. Using this scale, around six in ten Americans have either major (23%) or moderate (38%) concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, while about four in ten have either few (32%) or very few (7%) concerns.

Unsurprisingly, most Americans who have major concerns about COVID-19 vaccines are either hesitant (49%) or refusers (34%), while 17% are accepters, despite their concerns. Among those with moderate concerns, a majority (55%) are vaccine accepters, while 35% are hesitant and 9% are refusers. Nearly nine in ten of those with few concerns (86%) are vaccine accepters, while 9% are hesitant and 4% are refusers. Interestingly, the share of vaccine accepters who have very few concerns is somewhat smaller (77%), while the share of refusers (17%) is larger than it is among those with moderate or few concerns.

Majorities of Americans across the political spectrum express at least moderate concerns about the vaccines. Two-thirds of Republicans (67%) hold at least moderate concerns, compared to 60% of independents and 56% of Democrats. Republicans who most trust Fox News (62%) or mainstream news sources (61%) are about as likely as all Republicans to have at least moderate concerns about the vaccines, but Republicans who most trust far-right television sources (75%) or do not watch television news (73%) are more likely to report moderate or major concerns.

With the exception of Jewish Americans (47%), majorities of Americans of all major religious groups report at least moderate concerns about COVID-19 vaccines. Around seven in ten Hispanic Catholics (72%), Hispanic Protestants (71%), non-Christian religious Americans (69%), white evangelical Protestants (68%), other Protestants of color (68%), other Christians (68%), Black Protestants (67%), and Mormons (63%) report moderate or major concerns about vaccines. Majorities of white Catholics (55%), white mainline Protestants (54%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (54%) express at least moderate concern about vaccines. Less than half of Jewish Americans (47%) have moderate or major concerns.

White Americans and multiracial Americans are less likely than Americans of other races to express concerns about vaccinations. Seven in ten Hispanic Americans (71%) and Black Americans (70%) have at least moderate concerns about vaccines. Smaller majorities of Americans of other races (62%), white Americans (57%), and multiracial Americans (57%) have at least moderate concerns about vaccines.

Concerns about COVID-19 vaccines decrease with greater levels of education. Among those with a high school degree or less, nearly three in four (73%) have at least moderate concerns, including about one-third who have major concerns. Around six in ten Americans with some college experience (62%) have at least moderate concerns. By contrast, half of Americans (50%) with four-year college degrees, and only four in ten Americans with postgraduate degrees (40%), have at least moderate concerns.

Less than half of Americans over age 65 (47%) report at least moderate concerns, and Americans over age 75 are even less likely to report concerns (40%). Young Americans ages 18–29 (62%), ages 30–49 (68%), and ages 50–64 (64%) are more likely to express concerns aboutCOVID-19 vaccines.

Women are significantly more likely than men to express concerns with COVID-19 vaccines. Two-thirds of women (67%) express at least moderate concerns, including 28% who express major concerns. A majority of men (55%) express at least moderate concerns, including 19% who express major concerns.

Notably, three in ten (30%) of those who have major concerns about the safety of the vaccine and are vaccine hesitant say that faith-based approaches would make them more likely to be vaccinated. More than one in five of those with moderate concerns (22%) say the same, as do 32% of those who have few concerns. Among refusers, 7% of those with major concerns, 7% of those with moderate concerns, and 13% of those with few concerns indicate that faith-based approaches could move them toward vaccine acceptance.

The Role of Religion in Vaccine Attitudes

Vaccination As an Example of Loving Your Neighbor

A majority of Americans (53%) agree with the statement “Because getting vaccinated against COVID-19 helps protect everyone, it is a way to live out the religious principle of loving my neighbors,” while 44% disagree with the statement. Americans who are hesitant to get vaccinated are much less likely than those with no hesitations to agree with this statement. Seven in ten Americans who are vaccine accepters (70%), compared to 40% of those who are vaccine hesitant and just 14% of those who are vaccine rejecters, agree that getting vaccinated is a way to show love for their neighbors.

With the notable exceptions of white evangelical Protestants (46%) and Hispanic Protestants (49%), majorities of all major religious groups agree that getting vaccinated is a way to live out the religious principle of loving their neighbors. More than six in ten Jewish Americans (69%), Mormons (66%), non-Christian religious Americans (64%), and other Christians (61%) agree with the statement. Majorities of other Protestants of color (58%), white Catholics (57%), Hispanic Catholics (55%), white mainline Protestants (55%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (53%), and Black Protestants (52%) agree.

Two-thirds of Americans of other races (67%), compared to 54% of Hispanic Americans, 53% of white Americans, 50% of multiracial Americans, and 48% of Black Americans, agree that getting vaccinated is a way to show love for their neighbors.

There are distinct educational gaps over whether Americans agree that getting vaccinated is a way to express love for their neighbors. Americans with a high school degree or less (43%) are less likely than those with some college experience (53%), those who have four-year college degrees (64%), and those who have postgraduate degrees (70%) to agree. These educational differences are particularly pronounced among white Americans. White Americans without four-year college degrees are much less likely than those with at least a four-year degree to agree with the statement (46% vs. 67%).

Americans over age 65 (63%) are more likely than younger Americans to agree that getting vaccinated is a form of loving your neighbor. Around half of Americans ages 18–29 (52%), ages 30–49 (50%), and ages 50–64 (51%) agree.

God Will Protect the Faithful From COVID-19

Only about one in five Americans (21%) agree with the statement “God always rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from being infected with COVID-19,” compared to 76% who disagree. These views are similar to the views recorded in early fall 2020, when PRRI first asked this question. About 26% of Republicans, 18% of independents, and 20% of Democrats agree with this statement.

Hispanic Protestants (35%) and Hispanic Catholics (35%) are most likely to agree that God will protect them from being infected with COVID-19. About one in four white evangelical Protestants (26%), other Protestants of color (23%), and other Christians (23%) agree. One in five or less among other groups agree, including 20% of white mainline Protestants, 19% of members of other non-Christian religions, 18% of white Catholics, 16% of Mormons, and 12% of Jewish Americans. Black Protestants (38%) are the most likely to hold this belief, while religiously unaffiliated Americans (9%) are the least likely to do so. Black Protestants who are hesitant to get vaccinated (47%) are more likely to agree that God will protect them, but other religious groups do not show significant differences according to their vaccine hesitancy status.

Americans who say that religion is very or somewhat important in their lives are nearly four times as likely as those who say religion is not too important or not important at all in their lives to agree that God always rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from being infected with COVID-19 compared to those who say religion is not too important or not important at all in their lives (29% vs. 8%).

Black Americans (35%) and Hispanic Americans (30%) are more likely than members of other racial groups (19%), white Americans (17%), and multiracial Americans (17%) to agree that God always rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from being infected with COVID-19. Americans without college degrees are more than twice as likely as Americans with college degrees to agree with this statement (25% vs. 12%). The biggest gap in education is among Black Americans (41% vs. 19%), followed by Hispanic Americans (33% vs. 15%), Americans who identify as another race (25% vs. 15%), and white Americans (20% vs. 10%).

Belief in divine protection against COVID-19 more strongly affects vaccine attitudes among white Americans as compared to Black Americans. White Americans (34%) who are vaccine refusers are notably more likely than white Americans who are vaccine hesitant (19%) and white Americans who are vaccine accepters (11%) to agree that God always rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from being infected with COVID-19. By contrast, Black Americans who are vaccine accepters (26%) are notably less likely than Black Americans who are vaccine hesitant or refusers (45%) to believe in divine protection against COVID-19.[9]

Trust in Community Religious Leaders

Around four in ten Americans (42%) report trusting religious leaders in their communities to do what is right at least most of the time, including 9% who trust them almost all of the time. Americans are more likely to trust religious leaders than they are to trust political leaders (19%) or business leaders (26%) in their communities.

Mormons (75%) and white evangelical Protestants (67%) are much more likely than other religious groups to trust religious leaders in their communities to do what is right. Majorities of other Protestants of color (58%), white mainline Protestants (56%), and white Catholics (55%) trust religious leaders to do what is right most of the time. Around four in ten Jewish Americans (43%), Black Protestants (40%), and Hispanic Protestants (39%) trust religious leaders in their communities. Around one-third or less of other Christians (35%), Hispanic Catholics (34%), and non-Christian religious Americans (28%) trust local religious leaders. Religiously unaffiliated Americans (16%) are least likely to report trusting local religious leaders.

Unsurprisingly, Americans who say that religion is very important to their lives are more likely to trust religious leaders in their communities. Six in ten Americans who say religion is very important to them (62%), compared to significantly fewer who say religion is somewhat important (43%), not too important (30%), or not at all important (15%), say they can trust religious leaders at least most of the time.

Nearly half of white Americans (48%) trust local religious leaders in their communities to do what is right most of the time. Around one-third of multiracial Americans (36%), Americans of other races (34%), Black Americans (32%), and Hispanic Americans (31%) say the same.

Younger Americans are less likely to report trusting religious leaders in their communities. Around one-third of Americans ages 18–29 (31%) and ages 30–49 (35%), compared to half of Americans ages 50–64 (48%) and a majority of Americans over age 65 (56%), trust religious leaders at least most of the time.

Religious Leaders As a Source for Vaccine Information

About one-third of Americans (32%) say they would, or did, in the case of those who have already received a vaccine, look to a religious leader for information when deciding whether to get a COVID-19 vaccine, including 3% who said they would consult religious leaders a lot, 12% who would consult religious leaders some, and 17% who would consult religious leaders a little. Democrats (29%) and independents (30%) are less likely than Republicans (38%) to report turning to religious leaders for information about vaccines.

Half or more of Mormons (55%), Black Protestants (52%), and other Protestants of color (50%) report they would or did look to religious leaders for information about the vaccines at least a little. More than four in ten other Christians (46%), Hispanic Protestants (45%), Hispanic Catholics (44%), and white evangelical Protestants (43%) would turn to religious leaders for information, as would about one-third of non-Christian religious Americans (32%). Fewer white mainline Protestant (27%), white Catholic (27%), Jewish (18%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (13%) would do the same.

Among those who are hesitant to get vaccinated, 70% of Black Protestants, 66% of white evangelical Protestants, 53% of Hispanic Catholics, 43% of white Catholics, 36% of white mainline Protestants, and 21% of religiously unaffiliated Americans would turn to religious leaders for information on vaccines at least a little.[10]

Among Americans who say that religion is very or somewhat important in their lives, 43% say they would turn to religious leaders at least a little for information about vaccines, compared to only 13% of those who say religion is not too important or not important at all in their lives. Similarly, among those who attend religious services at least a few times a year, 56% would turn to religious leaders, compared to 25% of those who seldom or never attend religious services.

Majorities of Americans report they are likely to turn to health care providers (85%), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (81%), family or friends (79%), local health departments (77%), and news outlets on television, in print, or online (66%) at least a little for information about vaccines. One-third (32%) of Americans turn to social media at least a little for information about vaccines.

Religiously Based Vaccine Refusals

A majority of Americans (56%) favor allowing individuals who would otherwise be required to receive a COVID-19 vaccine to refuse if doing so violates their religious beliefs, compared to 42% who are opposed. The percentage of Americans favoring such religiously based refusals has increased by six percentage points since early fall 2020, when Americans were evenly divided on this question (48% favor vs. 51% oppose).

About three in four Republicans (74%), 56% of independents, and 42% of Democrats favor allowing individuals to refuse vaccination on religious grounds.

Majorities of most religious groups favor allowing individuals to refuse vaccination on religious grounds, including white evangelical Protestants (81%), Mormons (75%), other Protestants of color (67%), Black Protestants (61%), white mainline Protestants (60%), Hispanic Protestants (59%), other Christians (59%), white Catholics (55%), and Jewish Americans (50%). Less than half of Hispanic Catholics (45%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (43%), and members of non-Christian religions (41%) favor allowing individuals to refuse vaccination on religious grounds. Among Americans who say that religion is very or somewhat important in their lives, 64% favor allowing individuals to refuse vaccination on religious grounds, compared to 43% of those who say religion is not too important or not important at all in their lives.

Majorities of multiracial Americans (63%), white Americans (59%), and Black Americans (59%) favor allowing individuals to refuse vaccination on religious grounds, as do 47% of Hispanic Americans and 45% of Americans who identify with other racial groups. College-educated Americans are notably less likely than those without college degrees to favor vaccine refusals on religious grounds (50% vs. 59%). The biggest gap in education is among white Americans, among whom 51% with four-year college degrees and 64% without four-year degrees favor allowing religiously based vaccine refusals.

Young Americans ages 18–29 (50%) are notably less likely than Americans ages 30–49 (59%) and Americans ages 60–64 (60%) to favor allowing individuals to refuse vaccination on religious grounds, but do not differ significantly from Americans ages 65 and older (53%).

Some of the willingness to allow religiously based refusals could be related to concerns about the vaccines themselves. Americans who express major concerns with the vaccines (71%) are notably more likely than those who express moderate concerns (57%), some concerns (46%), and a few concerns (52%) to favor allowing individuals to refuse a vaccine on religious grounds.

COVID-19 Impacts and Getting Vaccines to Groups Most Impacted

Economic and Health Impacts of COVID-19

More than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, more than two-thirds of Americans (68%) have directly experienced either economic or health-related consequences. More than one in ten Americans have reported losing their jobs (14%), while one in four (25%) report having their hours or pay cut over the past year. Americans are more likely to report experiences with the health impacts of COVID-19. Four in ten Americans (42%) report knowing someone who has been hospitalized due to COVID-19, and more than one-third (35%) report knowing someone who has died from the virus. Just under one in five Americans say that they or someone in their household have gotten sick with symptoms of COVID-19 (16%) or tested positive for the virus (16%), and 3% say they or someone in their household have been hospitalized because of the virus.

People of color are most likely to have experienced the negative economic consequences from the pandemic over the past year. More than one-third of multiracial Americans (37%) and around one-third of Hispanic Americans (32%) say they have had their hours or pay cut, compared to around one in four or less of Black Americans (25%), white Americans (23%), and Americans of other races (21%). About one in five multiracial Americans (20%), Black Americans (19%), and Hispanic Americans (18%) report losing their jobs, significantly higher than the shares of white Americans (12%) and Americans of other races (10%). White Americans without four-year college degrees (13%) are slightly more likely than white Americans with four-year degrees to report losing their jobs (10%). These education gaps in job losses are similar among Black Americans (19% of non-college graduates, 17% of college graduates) and Hispanic Americans (19% of non-college graduates, 16% of college graduates).

People of color are also more likely to report experiencing negative health consequences of the pandemic. More than one in five Hispanic (24%) and multiracial Americans (22%), compared to significantly fewer white Americans (15%), Americans of other races (13%), and Black Americans (12%), report that they or someone in their household have tested positive for COVID-19. Multiracial (24%) and Hispanic Americans (21%) are also significantly more likely than white (16%), Black (12%), and Americans of other races (12%) to say they or someone in their household experienced COVID-19 symptoms. Just under half of Hispanic Americans (47%) and Black Americans (45%), compared to smaller shares of multiracial Americans (36%), Americans of other races (34%), and white Americans (30%), report knowing someone who died from COVID-19. Despite the relatively small share of the groups, Americans of other races (5%), Black Americans (4%), and Hispanic Americans (4%) are more likely than white Americans (2%) to say they or someone in their household was hospitalized because of COVID-19.

Hispanic Protestants (20%), other Christians (20%), Black Protestants (18%), Hispanic Catholics (17%), members of non-Christian religions (17%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (15%) are most likely to report losing their jobs. About three in ten Hispanic Protestants (34%), Hispanic Catholics (33%), Mormons (31%), non-Christian Americans (28%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (27%) report having their work hours or pay cut.

About one in four Hispanic Protestants (28%) and Hispanic Catholics (24%) say they have tested positive for COVID-19 at some point. Mormons (26%), Hispanic Protestants (22%), Hispanic Catholics (21%), and white evangelical Protestants (19%) are most likely to report experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. Mormons (51%), Hispanic Protestants (51%), other Christians (51%), Black Protestants (48%), white evangelical Protestants (47%), and Jewish Americans (47%) are most likely to report knowing someone who has been hospitalized. About half of Hispanic Protestants (53%), Black Protestants (48%), Hispanic Catholics (47%), other Christians (45%), and non-Christian religious Americans (43%) report knowing someone who has died from COVID-19.

Vaccine Distribution Concerns

Black People, Hispanic People, and Native Americans

Around six in ten Americans are either somewhat or very confident that vaccine distribution is taking into account the needs of Native Americans (57%), Black people (62%), and Hispanic people (63%). Less than one in five Americans are very confident that the needs of Black people (19%), Hispanic people (18%) and Native Americans (16%) are being taken into account.

Republicans are more confident in the needs of these groups being taken into account than are independents or Democrats. About seven in ten Republicans (73% for Black people, 71% for Hispanic people, 68% for Native Americans), compared to smaller shares of independents (62% for Black people, 64% for Hispanic people, and 56% for Native Americans) and Democrats (55% for Black people, 57% for Hispanic people, 50% for Native Americans), are at least somewhat confident that the needs of Black people, Hispanic people, and Native Americans are being taken into account.

Black Americans are less likely than Americans of other races to say their needs are being taken into account. Around half of Black Americans (49%) say this, compared to around six in ten white Americans (64%), Hispanic Americans (61%), Americans of other races (60%), or multiracial Americans (59%). Black Americans (22%) and multiracial Americans (19%) are about twice as likely as Hispanic Americans (11%), white Americans (9%), and Americans of other races (6%) to say they are not at all confident that vaccine distribution will take into account the needs of Black people.

Hispanic Americans (64%) are about as likely as white Americans (64%), multiracial Americans (61%), and Americans of other races (59%) to feel that the needs of Hispanic people are being taken into account in vaccine distribution. Black Americans (51%) are substantially less likely to believe the needs of Hispanic people are being taken into account.

A majority of Americans (54%) of other races (which includes Native Americans) as well as 59% of Hispanic Americans, 58% of white Americans, and 51% of multiracial Americans are at least somewhat confident that the needs of Native Americans are being taken into account, compared to less than half of Black Americans (45%).

Religious People

Seven in ten Americans (71%) are confident that the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine is taking into account the needs of religious people, including one in five (20%) who are very confident that the needs of religious people are being taken into account.

Around seven in ten members of each partisan group believe that the needs of religious people are being taken into account. This includes 69% of independents, 71% of Republicans, and 77% of Democrats.

Substantial majorities of each major religious group are at least somewhat confident that the needs of religious people are being taken into account in vaccine distribution. White Catholics (80%) are most likely to be confident, followed by more than three in four white mainline Protestants (77%), Jewish Americans (77%), Mormons (76%), and non-Christian religious Americans (76%). Around seven in ten Hispanic Catholics (72%), other Christians (71%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (71%), white evangelical Protestants (68%), and other Protestants of color (68%) are confident that the needs of religious people are being taken into account. Black Protestants (62%) and Hispanic Protestants (59%) are the least likely to be confident that the needs of religious people are being taken into account.

Rural Communities

Six in ten Americans (60%) say that the needs of people living in rural communities are being taken into account in distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. Residents of rural areas (62%) are just as likely as residents of urban (59%) and suburban areas (61%) to be at least somewhat confident that the needs of rural Americans are being taken into account.

Majorities of white Americans (62%), Hispanic Americans (62%), Americans of other races (58%), multiracial Americans (56%), and Black Americans (51%) believe the needs of rural communities are being taken into account.

Religious groups differ somewhat in their confidence that vaccine distribution is taking into account the needs of people in rural communities. Around two-thirds of white Catholics (69%), Hispanic Catholics (66%), and white mainline Protestants (65%), compared to around six in ten Jewish Americans (62%), Mormons (62%), other Christians (61%), white evangelical Protestants (61%), non-Christian religious Americans (59%), Hispanic Protestants (58%), and other Protestants of color (57%) are at least somewhat confident that the needs of rural Americans are being taken into account. Fewer religiously unaffiliated Americans (54%) and Black Protestants (49%) are confident that the needs of rural Americans are being considered.

QAnon Conspiracy Beliefs and Vaccine Hesitancy

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the subject of several conspiracy theories, and existing conspiracy groups, such as QAnon, have encouraged disinformation about the pandemic and vaccination. To investigate the interaction of conspiracy theories and COVID-19, the survey asked a series of questions about QAnon conspiracy theories.

The QAnon Conspiracy Scale

QAnon beliefs are measured using a three-point composite index based on four questions that asked Americans to what extent they agree with the following statements, summarized in Table 4.1.[11]

The additive scale was recoded into three groups: those who completely disagree with all four statements (39%), those who give a variety of responses and remain mostly negative toward the conspiracy theories (48%), and those who give a variety of responses and are more likely to agree with the conspiracy theories or agree with all four statements (13%).

Republicans (20%) are notably more likely than independents (11%) and Democrats (8%) to generally agree with QAnon theories. By contrast, a majority of Democrats (56%) completely disagree with these theories, compared to 40% of independents and 21% of Republicans. A majority of Republicans (59%), nearly half of independents (49%), and over one-third of Democrats (36%) hold mixed but generally negative views of QAnon beliefs.

About one in five white evangelical Protestants (20%), Hispanic Protestants (18%), Mormons (17%), Black protestants (16%), other nonwhite Protestants (16%), Hispanic Catholics (16%), and members of non-Christian religions (15%) generally agree with QAnon conspiracy theories, as do 13% of other Christians, 11% of white Catholics, and 9% of religiously unaffiliated Americans. Jewish Americans (4%) are the least likely to hold these beliefs and, with religiously unaffiliated Americans (56%), are the most likely to completely disagree with these theories (60%).

White evangelical Protestants (19%) are least likely to completely disagree with QAnon conspiracy theories, as are about one in four Hispanic Protestants (25%) and Mormons (24%). About three in ten Black Protestants (30%), Hispanic Catholics (29%), and other Protestants of color (28%) completely disagree with all four conspiracy theories, and about four in ten or more other Christians (45%), members of non-Christian religions (45%), white Catholics (44%), and white mainline Protestants (39%) are in the completely disagree category.

QAnon Conspiracy Beliefs and Vaccine Hesitancy

There is a clear relationship between vaccine hesitancy and refusal and belief in QAnon conspiracy theories. Only 5% of Americans who are vaccine accepters generally agree with QAnon conspiracy theories, compared to 17% of those who are vaccine hesitant and nearly four in ten Americans (38%) who are vaccine refusers. By contrast, a majority of vaccine accepters (54%) completely disagree with all four theories, compared to only 22% of the vaccine hesitant and 12% of vaccine refusers.

Interestingly, those who agree with QAnon conspiracy theories are also those most likely to be movable to overcoming vaccine hesitancy using faith-based approaches. Among those who generally agree with QAnon conspiracy theories and who are vaccine hesitant, more than one-third (36%) say one or more of the faith-based approaches would make them at least somewhat more likely to get a vaccine. About one in four (26%) of those who are vaccine hesitant and mixed but generally disagree with QAnon theories and 21% of those who are hesitant and completely disagree with QAnon theories report that faith-based approaches might change their minds. Among vaccine refusers, the effectiveness of faith-based approaches does not vary significantly by QAnon conspiracy beliefs.

The evidence is that white evangelicals especially, have largely abandoned their right to think for themselves and form their own evidence-based opinions in favour of cult-think and being told what to believe by their church leaders, who are now abusing the power that gives them to pursue self-aggrandizing agendas and political systems and parties over which they have influence.

An unholy alliance between the neo-fascist political right, tax-exempt religious fundamentalism, gun-nuts and the cult of greed and selfishness - as exemplified by Donald Trump and his criminal cabal.

Meanwhile the fewer people who are vaccinated against the coronavirus, the greater the probability of a new, antibody evading strain emerging which could threaten to undo the major achievements of medical science in producing a range of highly effective, safe vaccines in under a year -the result of a mammoth effort and the international cooperation of hundreds of thousands of biomedical scientist on an unprecedented scale.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.