Nature’s great survivors: Flowering plants survived the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs

Despite creationist claims that their putative creator god created Earth and set the parameters of the universe to make it perfect for human life, Earth is not a very safe place to live. Most of it is actually hostile to human life, being either too cold, too hot, under water or too high for there to be enough partial pressure of oxygen to survive for long.

It is also subject to regular, non-discriminatory natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, droughts, or devastating floods. In the last few days, tens of thousands of people have dies in Morocco and Libya because of natural disasters.

And Earth is occasionally hit by an asteroid that changes the climate so radically that a mass extinction occurs, like the one, 66 million years ago, that exterminated all the dinosaurs except for a few feathered varieties that went on to become birds - the K-T extinction, more correctly known as the K-Pg extinction or boundary. (K is the initial letter of the German word for Cretaceous, and Pg is for Paleogene, which used to be called the Triassic)

Tell me all about the K-Pg boundary mass extinction.Although many plant species also became extinct in that event, and the resulting catastrophic climate change, a few did not, and some of the angiosperms (flowering, seed-bearing, plants) survived to come to dominate the plant life on Earth in much the same way that mammals and birds came to 'inherit the Earth' from the reptiles. Quite why they were able to do this is the subject of a paper in Biology Letters, by Jamie B. Thompson of the University of Bath, UK and Dr. Santiago Ramírez-Barahona of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico.

The K-Pg boundary mass extinction, also known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event, is one of the most significant and well-known mass extinctions in Earth's history. It occurred approximately 66 million years ago, marking the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods. This event had a profound impact on the planet's ecosystems, resulting in the extinction of numerous species, including the non-avian dinosaurs, and reshaping the Earth's biodiversity. Here are some key details about the K-Pg boundary mass extinction:The K-Pg boundary mass extinction serves as a key event in Earth's history, reshaping the planet's ecosystems and allowing for the rise of new forms of life. It has been extensively studied and is a subject of ongoing research to understand its full impact on Earth's biodiversity and the mechanisms that allowed certain species to survive while others perished.

- Causal Event: The primary cause of the K-Pg boundary mass extinction is widely believed to be a catastrophic asteroid impact. This impact event occurred near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico and created the Chicxulub crater, which is over 180 kilometers (112 miles) in diameter.

- Asteroid Impact: The asteroid responsible for the extinction event is estimated to have been around 10 kilometers (6 miles) in diameter. The impact would have released an immense amount of energy, causing widespread fires, tsunamis, and a "nuclear winter" effect, as massive amounts of dust and debris were ejected into the atmosphere.

- Environmental Effects: The impact had several profound and immediate environmental effects, including:

- Massive fires due to the reentry of ejected material.

- A "nuclear winter" effect, where sunlight was blocked by debris, leading to a dramatic drop in temperatures.

- Acid rain due to the release of sulfur compounds into the atmosphere.

- Global Consequences: These environmental effects resulted in a collapse of ecosystems worldwide. Photosynthesis was greatly reduced due to the diminished sunlight, leading to a decline in food sources and a disruption of the food chain. This had a cascading effect on both terrestrial and marine life.

- Extinction of Non-Avian Dinosaurs: The most iconic victims of the K-Pg extinction were the non-avian dinosaurs. These massive reptiles, which had dominated the Earth for millions of years, became extinct. However, some avian dinosaurs, which eventually gave rise to modern birds, did survive.

- Other Affected Organisms: In addition to dinosaurs, many other groups of organisms suffered severe losses, including marine reptiles (like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs), ammonites, and various terrestrial and marine species.

- Survivors: Despite the catastrophic nature of the event, some organisms did survive and went on to thrive in the aftermath. Mammals, for example, were relatively small and inconspicuous during the Cretaceous but diversified and expanded into various ecological niches after the extinction.

- Recovery and Evolution: After the K-Pg extinction event, Earth's ecosystems gradually recovered, and new species evolved to fill the ecological niches left vacant by the extinctions. The event marked the end of the Mesozoic Era and the beginning of the Cenozoic Era, which is characterized by the rise of mammals and the eventual appearance of modern ecosystems.

Dr Thompson has also published an article in The Conversation. His article is republished here under a Creative Commons licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Flowering plants survived the dinosaur-killing asteroid – and may outlive us

Jamie Thompson, University of Bath

If you looked up 66 million years ago you might have seen, for a split second, a bright light as a mountain-sized asteroid burned through the atmosphere and smashed into Earth. It was springtime and the literal end of an era, the Mesozoic.

If you somehow survived the initial impact, you would have witnessed the devastation that followed. Raging firestorms, megatsunamis, and a nuclear winter lasting months to years. The 180-million-year reign of non-avian dinosaurs was over in the blink of an eye, as well as at least 75% of the species who shared the planet with them.

Following this event, known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction (K-Pg), a new dawn emerged for Earth. Ecosystems bounced back, but the life inhabiting them was different.

Many iconic pre-K-Pg species can only be seen in a museum. The formidable Tyrannosaurus rex, the Velociraptor, and the winged dragons of the Quetzalcoatlus genus could not survive the asteroid and are confined to deep history. But if you take a walk outside and smell the roses, you will be in the presence of ancient lineages that blossomed in the ashes of K-Pg.

Many people think of plants as nice-looking greens. Essential for clean air, yes, but simple organisms. A step change in research is shaking up the way scientists think about plants: they are far more complex and more like us than you might imagine. This blossoming field of science is too delightful to do it justice in one or two stories.

This article is part of a series, Plant Curious, exploring scientific studies that challenge the way you view plantlife.

And the roses are an not unusual angiosperm (flowering plant) lineage in this regard. Fossils and genetic analysis suggest that the vast majority of angiosperm families originated before the asteroid.

Ancestors of the ornamental orchid, magnolia and passionflower families, grass and potato families, the medicinal daisy family, and the herbal mint family all shared Earth with the dinosaurs. In fact, the explosive evolution of angiosperms into the roughly 290,000 species today may have been facilitated by K-Pg.

Angiosperms seemed to have taken advantage of the fresh start, similar to the early members of our own lineage, the mammals.

Flowers are surprisingly resilient.

What do we know?

Fossils in different regions tell different versions of events. It is clear there was high angiosperm turnover (species loss and resurgence) in the Amazon when the asteroid hit, and a decline in plant-eating insects in North America which suggests a loss of food plants. But other regions, such as Patagonia, show no pattern.

A study in 2015 analysing angiosperm fossils of 257 genera (families typically contain multiple genera) found K-Pg had little effect on extinction rates. But this result is difficult to generalise across the 13,000 angiosperm genera.

My colleague Santiago Ramírez-Barahona, from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, and I took a new approach to solving this confusion in a study we recently published in Biology Letters. We analysed large angiosperm family trees, which previous work mapped from mutations in DNA sequences from 33,000-73,000 species.

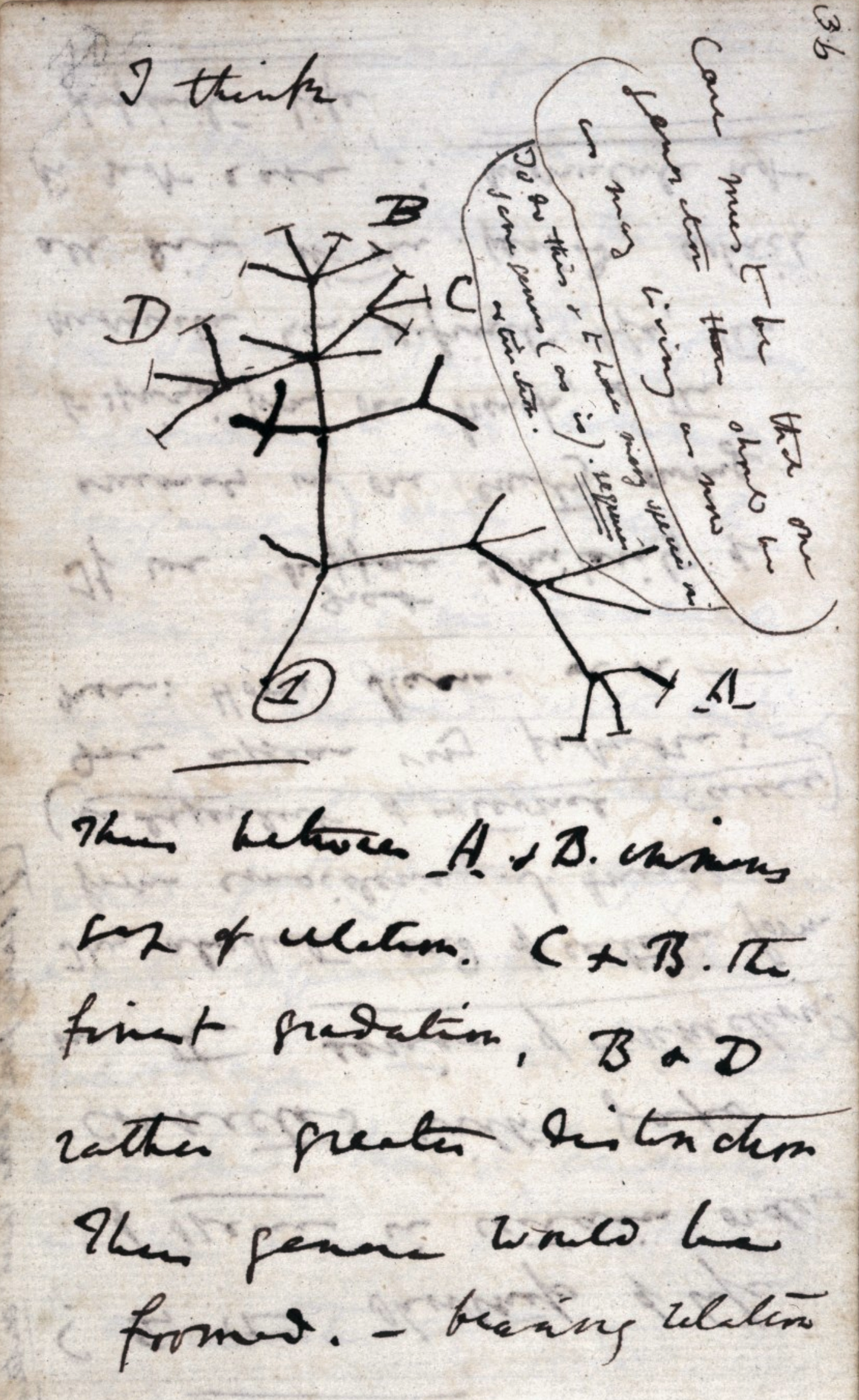

This way of tree-thinking has laid the groundwork for major insights about the evolution of life, since the first family tree was scribbled by Charles Darwin.

Although the family trees we analysed did not include extinct species, their shape contains clues about how extinction rates changed through time, through the way the branching rate ebbs and flows.

The extinction rate of a lineage, in this case angiosperms, can be estimated using mathematical models. The one we used compared ancestor age with estimates for how many species should be appearing in a family tree according to what we know about the evolution process.

It also compared the number of species in a family tree with estimates of how long it takes for a new species to evolve. This gives us a net diversification rate - how fast new species are appearing, adjusted for the number of species that have disappeared from the lineage.

The model generates time bands, such as a million years, to show how extinction rate varies through time. And the model allowed us to identify time periods that had high extinction rates. It can also suggest times in which major shifts in species creation and diversification have occurred as well as when there may have been a mass extinction event. It shows how well the DNA evidence supports these findings too.

We found that extinction rates seem to have been remarkably constant over the last 140-240 million years. This finding highlights how resilient angiosperms have been over hundreds of millions of years.

We cannot ignore the fossil evidence showing that many angiosperm species did disappear around K-Pg, with some locations hit harder than others. But, as our study seems to confirm, the lineages (families and orders) to which species belonged carried on undisturbed, creating life on Earth as we know it.

This is different to how non-avian dinosaurs fared, who disappeared in their entirety: their entire branch was pruned.

Scientists believe angiosperm resilience to the K-Pg mass extinction (why only leaves and branchlets of the angiosperm tree were pruned) may be explained by their ability to adapt. For example, their evolution of new seed-dispersal and pollination mechanisms.

They can also duplicate their entire genome (all of the DNA instructions in an organism) which provides a second copy of every single gene on which selection can act, potentially leading to new forms and greater diversity.

The sixth mass extinction event we currently face may follow a similar trajectory. A worrying number of angiosperm species are already threatened with extinction, and their demise will probably lead to the end of life as we know it.

It’s true angiosperms may blossom again from a stock of diverse survivors - and they may outlive us.

Jamie Thompson, Postdoctoral Evolutionary Biologist, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AbstractBy selecting two existing mega-phylogenies, there is an element of preselection of the descendants of taxons which didn't become extinct, so these results are not inconsistent with the fossil record which shows the loss of some other phylogenies, and the fossil record of the loss of plant-eating species which is indirect evidence of the loss of their food plant.

The Cretaceous–Palaeogene mass extinction event (K-Pg) witnessed upwards of 75% of animal species going extinct, most notably among these are the non-avian dinosaurs. A major question in macroevolution is whether this extinction event influenced the rise of flowering plants (angiosperms). The fossil record suggests that the K-Pg event had a strong regional impact on angiosperms with up to 75% species extinctions, but only had a minor impact on the extinction rates of major lineages (families and orders). Phylogenetic evidence for angiosperm extinction dynamics through time remains unexplored. By analysing two angiosperm mega-phylogenies containing approximately 32 000–73 000 extant species, here we show relatively constant extinction rates throughout geological time and no evidence for a mass extinction at the K-Pg boundary. Despite high species-level extinction observed in the fossil record, our results support the macroevolutionary resilience of angiosperms to the K-Pg mass extinction event via survival of higher lineages.

Figure 1. Macroevolutionary dynamics of angiosperms not negatively impacted at the K-Pg mass extinction event. Lineage through time plots (a) and phylogenies comprising approximately 32 000 and approximately 73 000 species (denoted as QJ and SB, respectively) indicate no apparent change across K-Pg. Generic-level extinction rates of angiosperms estimated with PyRate (b), adapted from [18], suggesting no significant difference in extinction rate following K-Pg. Phylogenetic extinction rates estimated by CoMET showing the detected mass extinctions with low support (Bayes factor lower than 6) (c), demonstrating that phylogenies do not support a mass extinction at the K-Pg. Trends in alternative models within congruence classes of both trees (d), showing that a pattern of resilience to K-Pg is supported despite non-identifiability of diversification rates. The geological timescale is visualized in each panel, and K-Pg is represented by vertical dashed lines in the plots and concentric lines in the phylogenies.Thompson Jamie B. and Ramírez-Barahona Santiago (2023)

No phylogenetic evidence for angiosperm mass extinction at the Cretaceous–Palaeogene (K-Pg) boundary

Biol. Lett. 192023031420230314 DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2023.0314

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by the Royal Society. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

But what should worry creationists who have had the courage to read this far, is the self-evident dependence on the Theory of Evolution by natural selection to explain these results. There is nothing to indicate that the creationist claims of mainstream biologists abandoning the TOE in favour of their childish superstition, complete with unexplained supernatural magic entities and evidence-free claims of regular interference with chemistry and physics, has any basis in reality, and every indication that it is a bare-faced lie intended to deceive a credulous and scientifically illiterate target audience.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.