Religion, Creationism, evolution, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about.

Sunday, 30 November 2025

Refuting Creationism - Why Would a Creator Create Life Around Hydrothermal Vents?

Discovery in the Deep Sea: Unique Habitat at Hydrothermal Vents

Here is something for creationists to run away from: why would a creator god who supposedly made the entire universe as a place for humans – especially American humans – to live, and arranged everything else for their benefit, create creatures in an environment so hostile that no human could survive there without specialised modern equipment? And how exactly did Noah collect two of each of the countless species that live there in great profusion, only to place them on the Ark and somehow maintain the extreme conditions they require?

The simple answer, as underscored by these discoveries, is that the whole tale is a childish fairy story. The organisms inhabiting the extreme conditions of deep-ocean trenches evolved to live there over millions of years, entirely independent of any usefulness to humans, whose existence is of supreme indifference to them.

The conditions described come from an open-access paper in Scientific Reports by an international team of oceanographers and marine biologists led by the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany. They detail a unique environment 1,300 metres below the surface on a flank of Conical Seamount in the western Pacific, off Lihir Island in Papua New Guinea. What makes it unique is not simply that it is a hydrothermal vent, but that it is coupled with a cold methane seep from deep sediment layers. Hot, mineral-rich water and cold, hydrocarbon-rich methane gas rise along the same pathways, producing vent fluids filled with bubbles of cold methane.

The result is a unique ecosystem comprising dense fields of the mussel Bathymodiolus, along with tube worms, shrimp, amphipods, and striking purple sea cucumbers coating the rocks so completely that the underlying surfaces are entirely concealed.

Before methane-producing sediments accumulated, the hydrothermal fluids were even hotter, leaving behind tell-tale deposits of gold and silver, as well as antimony, mercury, and arsenic. The various lifeforms have adapted to thrive amid these chemicals, some of which are highly toxic.

Hydrothermal vents are among the most extraordinary environments on Earth — geochemical oases on the seafloor where life thrives without sunlight, fuelled instead by chemical energy. They overturn several once-assumed “rules” of biology and offer important clues about evolution, extremophiles, and possibly even the origins of life.~

Friday, 30 August 2024

Refuting Creationism - How Mediterranean Biodiversity Evolved - 5.5 Million Years Before 'Creation Week'

Because they were so ignorant of the history of their part of the world, the origin myths made up by the Bronze Age authors of Genesis, told us nothing about the rich history of the sea that was almost on their doorstep, and the one in which they set daft tales like that of Jonah - the Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean Sea (the sea in the Middle of the Earth to the Romans) was central to history of the Middle East, Western Europe and North Africa but few people then could have been aware that the sea itself is a mere (on a geological timescale) 5.5 million years old in its present form.

It was formed firstly by the African plate pushing north towards Eurasia causing a water-filled depression to form that was originally connected to the Atlantic Ocean, but, as Africa pushed further north, causing mountains in modern-day Morocco and Spain to rise up, the Mediterranean became isolated and, with low inflow and high temperatures, what had been the Mediterranean Sea became a salt-filled depression, known to geologists as the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC) when the sea dried up leaving a thick deposit of salt and gypsum and of course exterminating just about all marine life.

Thursday, 22 August 2024

Refuting Creationism - Another Species Joins The List of Tool Makers and User - Humped Back Whales

Humpbacks Wield and Manufacture Tools – Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology

The humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, has one of the largest brains of any living species, beaten only by the larger blue whale, so it's not really surprising that it is yet another species that has been shown to do something that creationists like to use as 'proof' that humans are a special creation, apart from the rest of animal and plant life - the ability to manufacture and use tools.

As an aside, along with a fin whale, humpback whales are the only large whale species I have ever seen in the wild on a whale-watching trip from Boston, MA, USA about 12 years ago.

The tool they manufacture, then manipulate to give it maximum effect is the well-known 'bubble net', where a humpback circles round beneath a shoal of fish and blows a ring of bubbles which panic the fish into a tight group, through which the whale then rises with wide-open mouths, scooping hundreds or thousands of fish in a single mouthful. The process is repeated until the entire shoal has been consumed

At team of marine biologists from the Marine Mammal Research Program (MMRP) at University of Hawai'i, Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) and the Alaska Whale Foundation (AWF) have shown that not only do the whales manufacture this tool but then shape it to give it maximal efficiency.

What can you tell me about humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, and their hunting method of 'bubble netting'? Humpback whales, scientifically known as Megaptera novaeangliae, are large marine mammals famous for their acrobatic breaches and complex songs. These whales are found in oceans worldwide, migrating vast distances between feeding grounds in polar waters and breeding grounds in tropical or subtropical waters. Adult humpbacks typically range from 12 to 16 meters (39 to 52 feet) in length and can weigh up to 40 tons.They have just published their finding, open access, in the journal Royal Society Open Science, and a press release explaining their work:

Bubble Netting: A Unique Hunting Strategy

One of the most fascinating aspects of humpback whale behavior is their unique hunting technique known as bubble net feeding or bubble netting. This cooperative and highly coordinated method is primarily used to catch krill and small fish, such as herring and mackerel, which are the whales' main prey.

How Bubble Netting Works:

- Group Coordination:

- Bubble netting is a collaborative effort usually involving a group of humpback whales, although sometimes a single whale can perform a simplified version. The number of whales involved can range from a few individuals to a dozen or more.

- Creating the Net:

- One or more whales swim in a circle beneath a school of fish, blowing bubbles from their blowholes. These bubbles form a cylindrical "net" that traps and corrals the fish towards the center. The whales swim in an upward spiral, often releasing a continuous stream of bubbles to create the net.

- Herding the Prey:

- The bubbles and the noise made by the whales disorient and concentrate the prey into a tight ball. Some whales may produce loud vocalizations to further confuse the fish and drive them into the center of the net.

- The Final Strike:

- Once the prey is trapped in the bubble net, the whales swim upward with their mouths open, engulfing thousands of fish or krill in a single gulp. Often, several whales will surface together with their mouths wide open, filtering the water through their baleen plates to capture the prey.

Significance and Adaptation:

- Efficiency: Bubble netting is an incredibly efficient hunting strategy, allowing humpback whales to consume large amounts of prey with relatively little energy expenditure.

- Communication: The whales must communicate and coordinate their movements precisely to perform this complex behavior, which involves a high level of social interaction and possibly even culture among groups.

- Learning: Not all humpback whale populations engage in bubble netting. This behavior seems to be learned, passed down through generations, or shared between different groups of whales, indicating cultural transmission.

Bubble net feeding is a remarkable example of animal cooperation and ingenuity, showcasing the intelligence and adaptability of humpback whales in their quest for survival.

Humpbacks Wield and Manufacture Tools

In a study published today in Royal Society Open Science, researchers at the Marine Mammal Research Program (MMRP) at UH Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) and Alaska Whale Foundation (AWF) consider a new designation of the humpback whales they study: tool wielders.

Researchers have known that humpback whales create “bubble nets” to hunt, but they have learned that the animals don’t just create the bubble nets; they manipulate this unique tool in a variety of ways to maximize their food intake in Alaskan feeding grounds. This novel research demystifies a behavior key to the whales’ survival and offers a compelling case for including humpbacks among the rare animals that manufacture and wield their own tools.Many animals use tools to help them find food but very few actually create or modify these tools themselves. We discovered that solitary humpback whales in southeast (SE) Alaska craft complex bubble nets to catch krill, which are tiny shrimp-like creatures. These whales skillfully blow bubbles in patterns that form nets with internal rings, actively controlling details like the number of rings, the size and depth of the net, and the spacing between bubbles. This method lets them capture up to seven times more prey in a single feeding dive without using extra energy. This impressive behavior places humpback whales among the rare group of animals that both make and use their own tools for hunting.

Professor Lars Bejder, co-lead author

Director of MMRP

Marine Mammal Research Program

Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology

University of Hawaii at Manoa, Kaneohe, HI, USA.

Success in hunting is key for the whales’ survival. The population of humpback whales in SE Alaska overwinters in Hawaiʻi, and their energy budget for the entire year depends on their ability to capture enough food during summer and fall in SE Alaska. Unraveling the nuances of their carefully honed hunting technique sheds light on how migratory humpback whales consume enough calories to traverse the Pacific Ocean.

Advanced Tools & Partnerships are Key to Demystifying Whale Behavior

Marine mammals known as cetaceans include whales, dolphins, and porpoises, and they are notoriously difficult to study. Advances in research tools are making it easier to track and understand their behavior, and in this instance, researchers employed specialty tags and drones to study the whales’ movements from above and below the water.

We deployed non-invasive suction-cup tags on whales and flew drones over solitary bubble-netting humpback whales in SE Alaska, collecting data on their underwater movements. [The tools have incredible capability, but honing them takes practice]. Whales are a difficult group to study, requiring skill and precision to successfully tag and/or drone them.

William T. Gough, co-author

Marine Mammal Research Program

Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology

University of Hawaii at Manoa, Kaneohe, HI, USA.

The logistics of working in a remote location in SE Alaska brought its own challenges to the research.

We are so grateful to our research partners at the Alaska Whale Foundation (AWF) for their immense knowledge of the local area and the whales in that part of the world. This research would not have been possible without the strong collaborative effort with AWF.

Professor Lars Bejder.

More Insights and Improved Management to Come

Cetaceans throughout the globe face a slough of threats that range from habitat degradation, climate change and fisheries to chemical and noise pollution. One quarter of the 92 known cetacean species are at risk of extinction, and there is a clear and urgent need to implement effective conservation strategies on their behalf. How the animals hunt is key to their survival, and understanding this essential behavior makes resource managers better poised to adeptly monitor and conserve the feeding grounds that are critical to their survival.

This little-studied foraging behavior is wholly unique to humpback whales. It’s so incredible to see these animals in their natural habitat, performing behaviors that only a few people ever get to see. And it’s rewarding to be able to come back to the lab, dive into the data, and learn about what they’re doing underwater once they disappear from view.

William T. Gough.

With powerful new tools in researchers' hands, many more exciting cetacean behavioral discoveries lie on the horizon.This is a rich dataset that will allow us to learn even more about the physics and energetics of solitary bubble-netting. There is also data coming in from humpback whales performing other feeding behaviors, such as cooperative bubble-netting, surface feeding, and deep lunge feeding, allowing for further exploration of this population’s energetic landscape and fitness.

Professor Lars Bejder.What I find exciting is that humpbacks have come up with complex tools allowing them to exploit prey aggregations that otherwise would be unavailable to them. It is this behavioral flexibility and ingenuity that I hope will serve these whales well as our oceans continue to change.

Dr. Andy Szabo, c-lead author

AWF Executive Directo

Alaska Whale Foundation

Petersburg, AK, USA.

This groundbreaking work was made possible with support from Lindblad Expeditions - National Geographic Fund, the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and a Department of Defense (DOD) Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP) grant.

This study was conducted under a NOAA permit issued to Alaska Whale Foundation (no. 19703). All research was conducted under institution IACUC approvals.

AbstractSo, another one is added to the growing list of species that have abilities that were once claimed by creationists as proof of the unique, special creation of humans; an ability that takes intelligence, planning and, in the case of these whales, culture, since not all pods (yet) have this ability. When performing this technique as a group, it also involves planning, strategic thinking and communication in order to precisely coordinate the behaviour of each member of the pod.

Several animal species use tools for foraging; however, very few manufacture and/or modify those tools. Humpback whales, which manufacture bubble-net tools while foraging, are among these rare species. Using animal-borne tag and unoccupied aerial system technologies, we examine bubble-nets manufactured by solitary humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Southeast Alaska while feeding on krill. We demonstrate that the nets consist of internally tangential rings and suggest that whales actively control the number of rings in a net, net size and depth and the horizontal spacing between neighbouring bubbles. We argue that whales regulate these net structural elements to increase per-lunge prey intake by, on average, sevenfold. We measured breath rate and swimming and lunge kinematics to show that the resulting increase in prey density does not increase energetic expenditure. Our results provide a novel insight into how bubble-net tools manufactured by solitary foraging humpback whales act to increase foraging efficiency.

1. Introduction

Tool use can be broadly defined as ‘the external employment of an unattached environmental object to alter more efficiently the form, position, or condition of another object, another organism, or the user itself when the user holds or carries the tool during or just prior to use and is responsible for the proper and effective orientation of the tool’ [1]. While this definition is widely used, some researchers have also emphasized the purposeful nature of tool use [2] and the way tools serve as extensions of the body to solve problems for which evolution has not provided a specific morphological adaptation [3] as alternative perspectives on the phenomenon. This emphasis on intent and problem-solving highlights the role that animal cognition, innovation and ingenuity play in the evolution of tool use.

Several mammalian [2,4,5], avian [6,7], fish [8] and insect [9] lineages include species that use tools; however, while taxonomically widespread, tool-using species are relatively rare. Rarer still are species that manufacture and/or modify their tools. Well-studied examples include free-ranging chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and orangutans (Pongo abelii), who manufacture specialized tools for extracting insects and fruits [10–13]. Similarly, New Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides) and Goffin’s cockatoos (Cacatua goffiniana) manufacture wooden tools for extracting vegetation and seed matter [14–16]. Manufacturing tools in this way typically involves complex sequences of behaviour, such as selecting and detaching suitable vegetation, stripping bark and adjusting the resulting tool’s length and shape [14,17,18], to impose a novel, three-dimensional form onto natural material. This sophisticated, goal-directed behaviour, together with the comparatively large and complex brains that characterize tool-manufacturing species [19,20], has led researchers to suggest that the relative rareness of tool use and manufacture is cognitively constrained in its taxonomic distribution [11,15,19,21].

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) are known to produce complex bubble structures— ‘bubble-nets’ [22–25]. They do so by releasing air from their blowhole as they swim in a circular path below the surface. The rising bubbles form vertical curtains that appear as one or more rings from above. Aspects of bubble-nets and net-producing whales suggest that whales manufacture these nets as foraging tools [2]. For example, the use of bubble-nets has been observed repeatedly in association with foraging in allopatric humpback whale populations [23,24,26–29]. Several researchers have noted differences in the size and shape of bubble-nets produced by whales between, and notably within, the same populations [24,25,30]. Some of these differences correlate with the number of individuals participating in the use of the net and/or the different types of prey they are targeting (e.g. Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii), juvenile salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) and krill (Order: Euphausiacea) [24,25,30]), suggesting that whales can exert control over their structure. Indeed, humpback whales’ flexible, spindle-shaped bodies, elongated pectoral flippers with large, rounded tubercles on their leading edge and out-sized tails [29,31,32] probably provide them with sufficient maneuverability [33] to manufacture nets that increase foraging efficiency under specific conditions.

In this study, we use observations from individually feeding humpback whales manufacturing bubble-nets in Southeast Alaska to examine how whales employ these tools to increase their prey intake and/or to decrease their energetic expenditure. To do so, we incorporate unoccupied aerial systems (UAS, or ‘drones’) coupled with photogrammetry techniques and non-invasive animal-borne tags equipped with motion sensors and video cameras to characterize the behaviour of solitary net-producing humpback whales and the nets they produce. Specifically, we describe net features, such as bubble-net size, shape and inter-bubble distance (‘mesh size’, i.e. the horizontal spacing between neighbouring bubbles), and consider how these modifiable attributes can contribute to an increase in prey intake for net-producing whales versus non-net-producing foraging whales. We also examine breath rates, lunge kinematics and dive behaviour to explore potential energetic costs associated with deploying bubble-nets. In doing so, we provide novel insights into the benefits that tool use provides foraging whales.

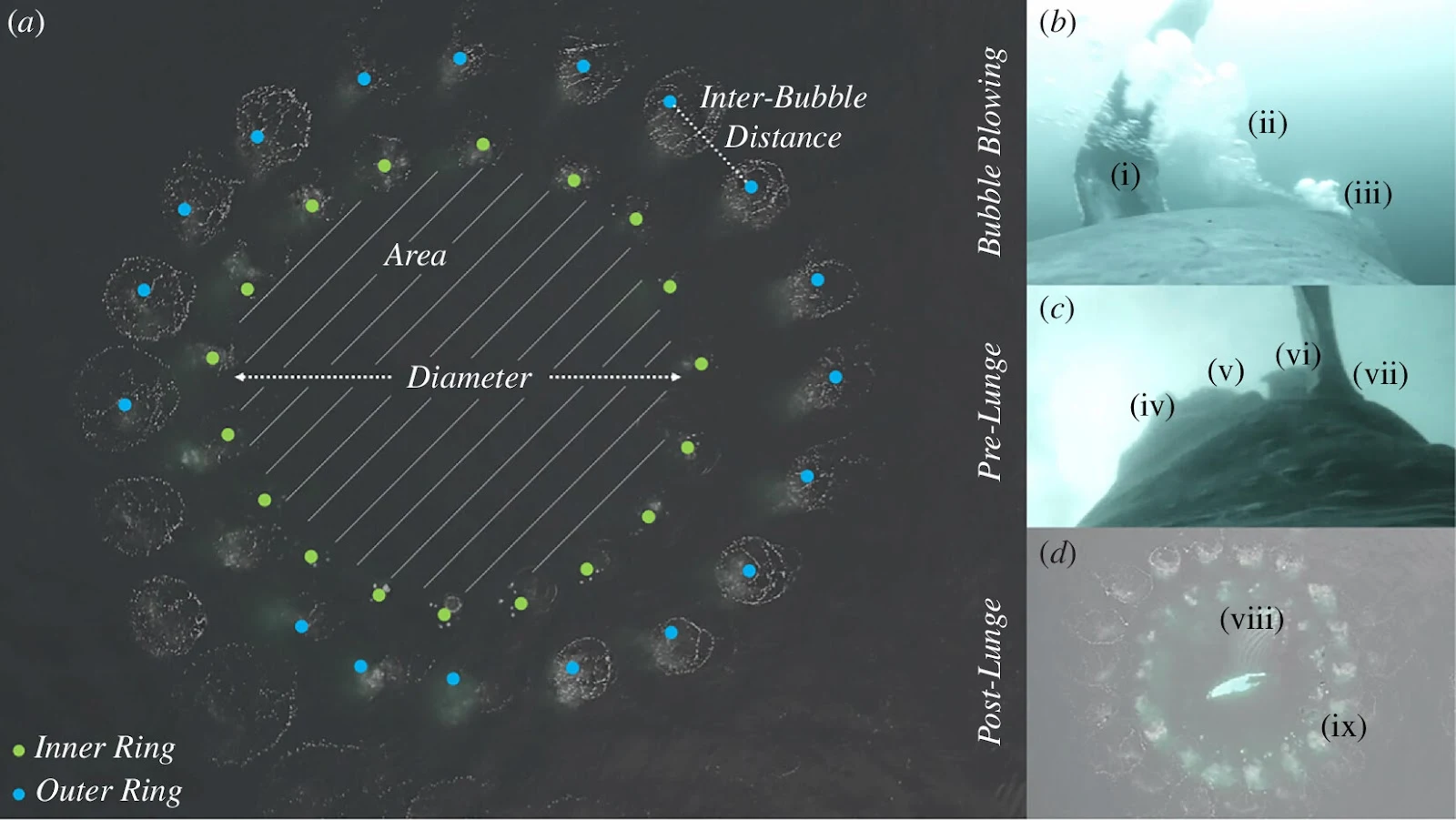

Figure 1. Variables and data collected from UAS and tagging methodologies. (a) UAS-derived bubble-net metrics for a two-ring bubble-net, including the area and diameter for the inner ring, and the horizontal inter-bubble distance (i.e. mesh size) for the outer ring. (b) Whale-producing bubble pulses, showing (i) left flipper, (ii) previous bubble pulse and (iii) new bubble pulse. (c) Whale with mouth open immediately prior to a lunge, with (iv) top jaw, (v) baleen rack, (vi) bottom jaw and (vii) right flipper visible. (d) Whale approaching the surface after a lunge, with the (viii) mouth closed prior to breaking the water’s surface and (ix) full bubble-net visible.

Figure 1. Variables and data collected from UAS and tagging methodologies. (a) UAS-derived bubble-net metrics for a two-ring bubble-net, including the area and diameter for the inner ring, and the horizontal inter-bubble distance (i.e. mesh size) for the outer ring. (b) Whale-producing bubble pulses, showing (i) left flipper, (ii) previous bubble pulse and (iii) new bubble pulse. (c) Whale with mouth open immediately prior to a lunge, with (iv) top jaw, (v) baleen rack, (vi) bottom jaw and (vii) right flipper visible. (d) Whale approaching the surface after a lunge, with the (viii) mouth closed prior to breaking the water’s surface and (ix) full bubble-net visible.

Figure 2. Data-driven simulation of a humpback whale manufacturing a bubble-net. (a) A zoomed-out view of average krill layer depth demonstrates the three-dimensional trajectory of a bubble-net feeding humpback whale from the start (white) to the end (pink) of the dive. (b) The UAS imagery alongside concurrent data-driven pre-lunge simulation showing 0.6 m s-1 rise rate of spherical cap leaders compared with 0.1 m s-1 rise rate for trailing capillary bubbles.Szabo, A.; Bejder, L.; Warick, H.; van Aswegen, M.; Friedlaender, A. S.; Goldbogen, J.; Kendall-Bar, J. M.; Leunissen, E. M.; Angot, M.; Gough, W. T.

Figure 2. Data-driven simulation of a humpback whale manufacturing a bubble-net. (a) A zoomed-out view of average krill layer depth demonstrates the three-dimensional trajectory of a bubble-net feeding humpback whale from the start (white) to the end (pink) of the dive. (b) The UAS imagery alongside concurrent data-driven pre-lunge simulation showing 0.6 m s-1 rise rate of spherical cap leaders compared with 0.1 m s-1 rise rate for trailing capillary bubbles.Szabo, A.; Bejder, L.; Warick, H.; van Aswegen, M.; Friedlaender, A. S.; Goldbogen, J.; Kendall-Bar, J. M.; Leunissen, E. M.; Angot, M.; Gough, W. T.

Solitary humpback whales manufacture bubble-nets as tools to increase prey intake Royal Society Open Science; 11(8) 240328; DOI: 10.1098/rsos.240328

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by the Royal Society. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Since this is a culturally transmitted, learned behaviour, there must have been a time when the skill was being perfected by careful observation, planning and experimentation, which implies simple scientific methodology and evaluation of the results.