Slideshow code developed in collaboration with ChatGPT3 at https://chat.openai.com/

Reconstruction of

Nimbadon lavarackorum mother and juvenile (detail)

The thing about having a counter-factual superstition like creationism is that you need to concoct increasingly unlikely explanation for your rejection of the sort of real-world evidence that normal people base their opinions on.

For example, we have in the following example, evidence that 15 million years ago, there were large marsupials living in Australia, one of which, known to science as

Nimbadon, weighed about 70Kg and climbed about in trees. The evidence is in the form of fossils, 24 of which were found in a few square metres of each other at one site within the

Riversleigh World Heritage site, Gregory, Queensland, Australia.

These fossils show that

Nimbadon belongs to an extinct group of marsupials called diprotodontoids, whose closest living relatives are wombats and Koalas.

Australian diprotodontoids

Australian diprotodontoids refer to a diverse group of marsupials that belong to the superfamily Diprotodontoidae. These unique animals are endemic to Australia and have a rich fossil record spanning several million years. They exhibit a wide range of body sizes, from small, rat-like forms to massive, herbivorous giants.

One prominent member of the Australian diprotodontoids is the extinct genus Diprotodon. Diprotodon was the largest known marsupial to have ever lived, reaching the size of a rhinoceros. It lived during the Pleistocene epoch and is often referred to as the "giant wombat" due to its resemblance to modern wombats. Diprotodon had a robust build, powerful limbs, and a specialized skull adapted for herbivorous feeding.

Another notable diprotodontoid is Zygomaturus, which lived during the late Miocene to the late Pleistocene. Zygomaturus was a large, herbivorous marsupial characterized by its elongated snout and peculiar cheek teeth. It is believed to have inhabited wetland and riparian environments.

Other diprotodontoids include Nototherium, Palorchestes, and Procoptodon. Nototherium was a medium-sized herbivore with an elongated skull, while Palorchestes was a peculiar genus with long arms and a unique grasping hand. Procoptodon, also known as the "short-faced kangaroo," had a short, robust face and incredibly long hind limbs.

References:

- Archer, M., Hand, S. J., & Godthelp, H. (1991). Riversleigh: The Story of Animals in Ancient Rainforests of Inland Australia. Reed Books.

- Long, J. A., Archer, M., Flannery, T. F., & Hand, S. J. (2002). Prehistoric Mammals of Australia and New Guinea: One Hundred Million Years of Evolution. University of New South Wales Press.

- Mackness, B. (2008). Australian Megafauna: Diprotodontoidae. In Janis, C., Gunn, A., & Uhen, M. (Eds.), Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America (Volume 2: Small Mammals, Xenarthrans, and Marine Mammals) (pp. 425-436). Cambridge University Press.

ChatGPT3. (2023). "Tell me about the Australian diprotodontoids."

[Retrieved from

https://chat.openai.com/]

Now all that, of course, is entirely inconsistent with creationist belief in an Earth that is just a few thousand years old and on which all living and extinct creatures, including dinosaurs and extinct Australian megafauna such as

Nimbadon, were created in the first week and lived contemporaneously until a genocidal global flood killed them all bar a few selected ones from whom all modern species are descended, and all fossils are of animals drowned in that flood just 4000 years ago.

So, how do creationists cope with the resulting cognitive dissonance between the real-world evidence and what they need to believe because not believing it would be a terrifying existential threat? They claim:

- All the dating methods palaeontologists and geologists use are wrong (by many orders of magnitude), even, bizarrely citing the fact that carbon dating has an accepted limitation to the age at which it can date objects accurately, when in fact, carbon dating isn't used to date fossils (because of that very limitation and also because any carbon in the fossil will be due to minerlisation and not derived from the body of the animal).

- The scientists are part of a conspiracy, often a Satanic or even Zionist conspiracy, of which all the scientists' assistants and all the staff of the publishing houses that publish the scientific journals are part, and none of whom has ever broken ranks and blown the whistle on the deception.

- The facts must be wrong because they are at odds with what the Bible says and the Bible is the inerrant word of God, so the Bible says.

- Scientists all hate God and want to turn people away from 'him'.

That bizarre and highly unlikely 'explanation' for the evidence is so much more convoluted and involving so many more entities, than the simple explanation - the scientists are telling the truth and the Bible is not literal truth - that any rational person would go with the most vicarious explanation as being the one most likely to be correct, especially since scientists keep producing more and more evidence for the latter alternative while creationists can find no evidence for the former.

What creationists can never admit is what is obvious to most normal people: that when their religion disagrees with science, their religion is wrong; science is a tool for discovering the truth.

and that was by way of introduction to a recent article in

The Conversation in which four palaeontologists describe

Nimbadon and discuss why they grew so large. The palaeontologists are:

- Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, Professor, Biological Sciences Department, University of Cape Town

- Karen Black, Leading Education Professional, UNSW Sydney

- Mike Archer, Professor, Pangea Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

- Sue Hand, Professor emeritus, UNSW Sydney

Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons Licence, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

These giant ‘drop bears’ with opposable thumbs once scaled trees in Australia. But how did they grow so huge?

Peter Schouten, Author provided

,

University of Cape Town;

Karen Black,

UNSW Sydney;

Mike Archer,

UNSW Sydney, and

Sue Hand,

UNSW Sydney

Although long dead, fossil skeletons provide an incredible window into the lifestyle and environment of an extinct animal.

By analysing the various features of fossil bones we can reveal not only the overall size and shape of the animal, but also what kind of movement the animal was capable of, its lifestyle, and the environment in which it lived.

But what if we looked

inside fossil bones? What secrets would it reveal about the growth and development of an extinct animal? In a newly published paper in the

Journal of Paleontology, we have done just that, using 15 million-year-old skeletons of a giant bear-like marsupial from the world-famous Riversleigh World Heritage Area (Boodjamulla) in Waanyi country of northwest Queensland.

Tree-dwelling wombat relatives

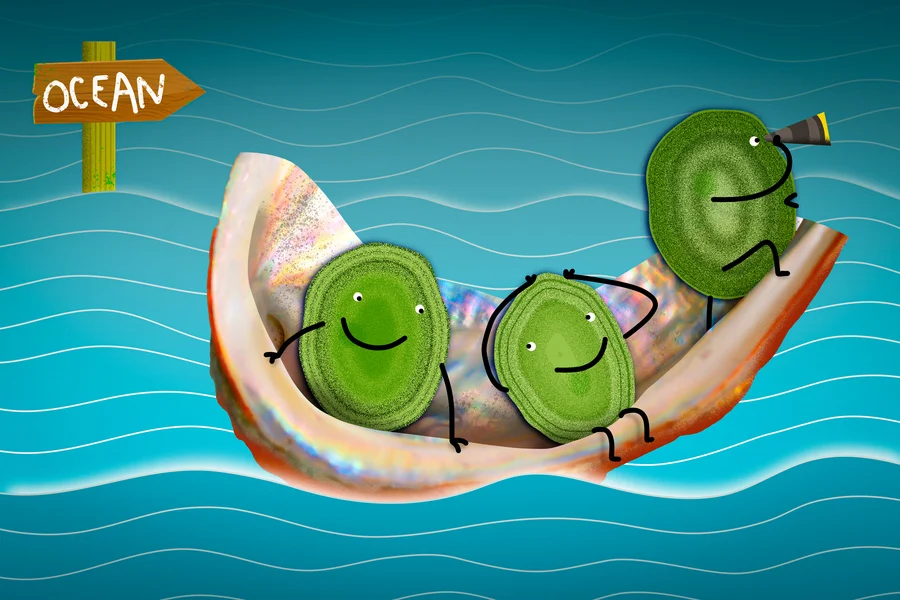

Reconstruction of a mother and baby

Nimbadon. They had powerful arms, large hands and feet and huge claws to assist climbing through the rainforest tree tops.

Peter Schouten, Author provided

The huge tree-dwelling herbivorous marsupials, known as

Nimbadon, weighed about 70kg, making them the largest arboreal (tree dwelling) mammals known from Australia.

Nimbadon belongs to a diverse group of long extinct, large-bodied marsupials

known as diprotodontoids, the likes of which include the largest marsupial to have ever lived, the 2.5 tonne megafaunal

Diprotodon, and bizarre trunked marsupials reminiscent of modern-day tapirs.

Among living animals,

Nimbadon is most closely related to wombats. Yet surprisingly, in terms of body size and lifestyle, they are more comparable to

sun bears, which today can be found scaling the rainforest canopies of Southeast Asia.

When we first uncovered jawbones of

Nimbadon at Riversleigh in 1993, we thought we were looking at very large leaf-eating marsupials who foraged for food on the forest floor.

Modern-day sun bears climb trees and lounge there much like sloths do.

But like many of the species we’ve unearthed from Riversleigh, the closer we look at these animals, the more bizarre and fascinating they become.

Nimbadon is now known from its complete skeleton, including material representing developmental ages ranging from tiny pouch-young to mature adults. It had strong arms with very mobile shoulder and elbow joints. Its hands and feet had specially adapted opposable thumbs with huge curved claws for climbing, penetrating bark and grasping branches.

These animals were highly specialised climbers and lived vastly different lifestyles compared to their closest living relatives – the land-dwelling, burrowing wombats.

Our initial research showed that

Nimbadon was not only a “tree-hugger”, but also a “tree-hanger”, spending some of its time suspended from tree branches like a sloth.

Fossil skeleton of a mature adult

Nimbadon.

Karen Black, Author provided

lived 15 million years ago in the canopy of lowland Australian rainforests. These biodiverse, lush forests were home to some equally strange animals: flesh-eating kangaroos, tree-climbing crocodiles, ancestral thylacines, cat- to leopard-sized marsupial lions, huge anaconda-like snakes, giant toothed platypuses and mysterious marsupials so strange they have been called “Thingodonta”. It was a very different Australia than the one we see today.

Sectioning the bones

Despite the wealth of information we have gleaned from

Nimbadon skeletons, until now we hadn’t fully understood the growth patterns of these ancient marsupials.

Were they affected by seasonality? How long did they take to grow to adult body size in the canopies of the ancient forest? Clues to these questions lay in the bones’ microscopic structure.

To look inside the fossil bones, we needed to select the right material. Long bones, such as the bones of the leg, are known to preserve a good record of growth, so we analysed ten long bones of several different-sized individuals.

Articulated fossilised Nimbadon skeletons in a large slab of limestone recovered from a 15 million year old fossil cave deposit in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area, northwestern Queensland.

Anna Gillespie, Author provided

We began by removing a section from the shaft of the bone, and embedded it in resin. Using a diamond-edged blade, we cut our samples into thin sections and polished them further until light could pass through them. These thinned sections were mounted on glass microscope slides to be studied.

Remarkably, even after millions of years of fossilisation, the microscopic structure of the fossil bones had remained intact. We were amazed to discover that

Nimbadon grew in periodic spurts. Individuals had fast growth periods, each followed by a slow growth period, often associated with a band of arrested growth.

Seasonal growers

Cyclical growth patterns have previously been documented for marsupials such as in the living western grey kangaroo. However, our results indicate that, overall, the limbs of

Nimbadon had a much slower, more extenuated growth than kangaroo limbs.

One individual recorded at least seven to eight growth cycles, which suggests this arboreal giant needed at least this amount of time – and probably more – to become a fully-grown, sexually mature adult.

Based on these alternating cycles of fast and slow growth,

Nimbadon may have been affected by seasonal conditions such as food availability. However, exactly how long it took for eight growth cycles to develop remains a mystery. If indeed they represent annual cycles, it would be at least eight years until sexual maturity, which is unusual in the modern marsupial world.

For example, kangaroos are sexually mature at one to two years. That being said,

Nimbadon is an unusual beast and a very large one at that, so an extended developmental period (and lifespan) is not unlikely.

Real-life drop bears

We have come to think about these strange arboreal marsupials as real versions of the legendary “drop bears” of Australian folklore – mysterious tree-dwelling creatures that would drop down on unsuspecting animals below.

Reconstruction of

Nimbadon’s palaeoenvironment of lush rainforest with underground caves.

Karen Black, Author provided

While moving in herds through the rainforest canopy, both young and adult

Nimbadon would have occasionally lost their grip before dropping down from the treetops. Sometimes they would end up in forest floor caves, which is where we have been finding their still-articulated skeletons.

Given the constant surprises that research into this extraordinary, extinct Riversleigh mammal has already produced, we are eager and prepared for still more.

Currently we are looking into wear in the enamel microstructure of

Nimbadon’s teeth to determine this legendary drop bear’s diet. We expect that what we find down the track will continue to upend our naïve first presumptions about the lifestyles of this and many of the other strange inhabitants of the ancient inland rainforests of Riversleigh.

Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan

Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, Professor, Biological Sciences Department,

University of Cape Town;

Karen Black, Leading Education Professional,

UNSW Sydney;

Mike Archer, Professor, Pangea Research Centre,

UNSW Sydney, and

Sue Hand, Professor emeritus,

UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from

The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the

original article.

Copyright: © 2023 The authors.

Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Paleontological Society. Open access.

(CC BY 4.0)The authors of that article have recently published their findings, open access, in the Journal of Paleontology:

Abstract

Despite the recognition that bone histology provides much information about the life history and biology of extinct animals, osteohistology of extinct marsupials is sorely lacking. We studied the bone histology of the ca. 15-million-year-old Nimbadon lavarackorum from Australia to obtain insight into its biology. The histology of thin sections of five femora and five tibiae of juveniles, subadult, and adult Nimbadon lavarackorum was studied. Growth marks in the bones suggest that N. lavarackorum took at least 7–8 years (and likely longer) to reach skeletal maturity. The predominant bone tissue during early ontogeny is parallel-fibered bone, whereas an even slower rate of bone formation is indicated by the presence of lamellar bone tissue in the periosteal parts of the compacta in older individuals. Deposition of bone was interrupted periodically by lines of arrested growth or annuli. This cyclical growth strategy indicates that growth in N. lavarackorum was affected by the prevailing environmental conditions and available resources, as well as seasonal physiological factors such as decreasing body temperatures and metabolic rates.

Figure 2.

Specimen AR21803.

(1) AR21803a, thin section BII; section of partial tibia; arrows indicate growth marks in the compacta;

(2) AR21803b, thin section AI; section of partial femur showing a low-magnification overview of the compacta; arrows indicate growth marks in the compacta (note the resorptive endosteal margin of the bone wall);

(3) AR21803b, thin section AI showing radial tract of compacted coarse cancellous bone (indicated by the white arrows). Images taken under polarized light with a one-quarter-λ compensator.

Not only convincing evidence of the existence of these giant wombat-like marsupials, 15 million years ago, but, as usual, not a hint that the scientists believe the Theory of Evolution is inadequate for explaining the observations, or that magic by an invisible supernatural magician is a better explanation.

In other words, yet another casual and incidental refutation of creationism and the claims made by the scientifically illiterate authors of the Bible.