Not content with increasing the suffering and misery in the world with its brilliantly designed Human Immunosuppressive Virus (HIV), creationism's favourite pestilential malevolence also produced a related virus, Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1).

HIV is a deadly, (normally) sexually-transmitted retrovirus which medical scientists has managed to bring under control, but not cure or eradicate or even produce a vaccine against. What they have produced are anti-retroviral drugs which prevent the virus replicating so it doesn't kill its victims and, more importantly it isn't passed on to sexual partners.

Sadly for creationists, they have been denied the excuse of 'genetic entropy' and 'devolution' to absolve their favourite sadist of responsibility for HIV because they have also jubilantly declared it to be a 'gay plague' sent by their 'loving' god to punish homosexuals for behaving how it designed them to behave.

HTLV-1 is not nearly so deadly as HIV when left untreated, but, being closely related to it, it uses the same modus operandi as HIV and in some cases causes cancer and neurodegenerative disease that can be more deadly and debilitating than HIV treated by anti-retroviral drugs.

Tell me about the virus HTLV-1, please. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is a retrovirus that primarily infects T-cells, a type of white blood cell involved in the immune response. It is closely related to HIV but is distinct in its effects and disease profile. HTLV-1 was the first human retrovirus discovered, identified in the late 1970s.Like HIV, HTLV-1 is a retrovirus that uses sneak tactics to hide from the immune system creationist's putative intelligent [sic] designer designed to protect us from the organisms it designed to infect us. It is an RNA virus that uses the enzyme reverse transcriptase to insert the DNA template for itself into the genome of the cells (mostly the T-Cells of the immune system) it infects.

Key Facts about HTLV-1:

- Transmission:

- Mother-to-child transmission: Typically through breastfeeding.

- Sexual contact: Particularly more common through unprotected sex.

- Blood-to-blood contact: Through contaminated needles, blood transfusions, and sharing needles among drug users.

- Geographical Distribution: HTLV-1 is endemic in several regions, including:

- Southwestern Japan

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- The Caribbean

- South America (particularly the Andes)

- Parts of the Middle East and Australia, especially among some Indigenous populations.

- Diseases Associated with HTLV-1:

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL): A rare but aggressive form of blood cancer that can develop years after infection.

- HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP): A chronic progressive neurological disorder that leads to weakness and paralysis of the legs.

- Other conditions: HTLV-1 is also associated with uveitis (eye inflammation), dermatitis, and other inflammatory conditions.

- Latency and Persistence:

- HTLV-1 can persist in the body for many years without causing symptoms. Only about 2-5% of infected individuals will develop ATL, and a similar percentage may develop HAM/TSP.

- Most people infected with HTLV-1 remain asymptomatic carriers for life.

- Diagnosis:

- Blood tests are used to detect HTLV-1 antibodies.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) testing can also confirm the presence of the virus by detecting its genetic material.

- Prevention and Control:

- There is no vaccine for HTLV-1.

- Preventative measures focus on reducing transmission, such as encouraging safe sexual practices, screening blood donations, avoiding breastfeeding if the mother is infected, and preventing needle sharing.

- Treatment:

- There is no cure for HTLV-1 infection, and treatment focuses on managing associated conditions. ATL is typically treated with chemotherapy, while HAM/TSP may be managed with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive therapies.

Because HTLV-1 infection is often asymptomatic, many people may be unaware they carry the virus, underscoring the importance of screening in high-risk populations.

How is it related evolutionarily to HIV, if at all?

HTLV-1 and HIV are both retroviruses, meaning they belong to a class of viruses that replicate through reverse transcription, converting their RNA genome into DNA inside a host cell. However, their evolutionary relationship is distant, as they belong to different families and have different mechanisms of causing disease.

Evolutionary Relationship:

- Same Retrovirus Class (Retroviridae):

- Both HTLV-1 and HIV are part of the broader group of retroviruses. Retroviruses are unique in that they reverse-transcribe their RNA into DNA, which then integrates into the host genome.

- Retroviruses can be divided into two main groups: oncogenic retroviruses (cancer-causing) and lentiviruses (slow viruses). HTLV-1 is part of the first group, while HIV belongs to the second.

- Different Families:

- HTLV-1 belongs to the Deltaretrovirus genus of the Retroviridae family.

- HIV belongs to the Lentivirus genus within the same Retroviridae family.

- Different Pathogenesis:

- HTLV-1 primarily causes oncogenic diseases like Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and neuroinflammatory diseases like HTLV-1 associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP).

- HIV leads to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) by attacking and depleting the immune system's CD4+ T cells, making the host vulnerable to opportunistic infections.

Shared Characteristics:

- Genome Structure: Both viruses contain an RNA genome that is reverse transcribed into DNA, which is integrated into the host cell's genome. This is a hallmark of all retroviruses.

- Integration into Host DNA: Both HTLV-1 and HIV insert their genetic material into the host's DNA, enabling long-term persistence in the host's cells.

- Transmission Methods: Both viruses can be transmitted through blood, sexual contact, and from mother to child.

Divergence:

- HTLV-1 is evolutionarily older than HIV. HTLV viruses have likely been infecting humans and non-human primates for tens of millions of years, while HIV emerged relatively recently in human history (likely in the early 20th century) from cross-species transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) from primates to humans.

- HIV likely arose from zoonotic transmissions from primates, whereas HTLV-1 appears to have co-evolved with human ancestors for a longer period of time.

In summary, although HTLV-1 and HIV share the basic characteristics of retroviruses, their evolutionary divergence into different viral families means that they are only distantly related. HTLV-1 belongs to an ancient lineage of viruses, whereas HIV's lineage evolved more recently from viruses infecting primates.

The research paper I'm reading gives HTLV-1 the full name 'human T cell leukemia virus type 1'. Is this the same virus?

Yes, "human T cell leukemia virus type 1" and "human T-lymphotropic virus type 1" (HTLV-1) refer to the same virus.

The names reflect different aspects of its biology:

Over time, HTLV-1 became the more widely accepted term in order to include the various diseases associated with the virus, not just leukemia. However, both names refer to the same retrovirus.

- "Human T cell leukemia virus" highlights its association with Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), a rare but serious cancer of the T cells caused by the virus.

- "Human T-lymphotropic virus" emphasizes that it primarily infects T-lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) and has broader implications beyond leukemia, such as HTLV-1 associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP), a neuroinflammatory condition.

Once in the cell's genome, it will be replicated every time the cell replicates and will be there for the lifetime of the victim.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 5 and 10 million people are infected by HTLV-1 and although many of them will be asymptomatic, they can pass it on to other victims without realising it. About 5% of infected people will develop aggressive forms of diseases like adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma—a form of cancer with a prognosis of less than a year.

But medical science is making progress in understanding HTLV-1 and in particular it's structure as a first step to understanding its MO and particularly its weaknesses and vulnerability.

One such team of researchers is that led by Martin Obr and Florian Schur from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) who, with colleagues in the USA have produced a detailed analysis of the structure of this virus.

Their findings have just been published, open access, in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology and announced in an Institute of Science & Technology, Austria, news release:

A Viral Close-Up

HTLV-1: A unique virus

Almost everyone knows about HIV. Fewer people know about its relative, HTLV-1. However, HTLV-1 can cause serious illnesses, including cancer. To develop ways to combat this virus, understanding its structure is essential. Martin Obr and Florian Schur from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) and US colleagues now show the virus in close-up in a new paper, published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

Martin Obr is on edge, anxiously waiting for his train to the airport. A storm called “Sabine” is brewing, shutting down all public transport. He catches his flight from Frankfurt to Vienna just in time.

Obr spent the last days in Germany meticulously analyzing what he calls the “perfect sample”. This sample helped him and Florian Schur from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) decode the structure of a virus called HTLV-1 (Human T-cell Leukemia Virus Type 1).

In collaboration with the University of Minnesota and Cornell University, the scientists provide new details into the virus’ architecture using Cryo-Electron Tomography (Cryo-ET)—a method to analyze the structures of biomolecules in high resolution. Their results were published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

The cousin of HIV

Obr and Schur first crossed paths while working on HIV-1 (Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1), aiming to better understand its structure. Obr then joined Schur’s research group at ISTA as a postdoc. They shifted their focus to HTLV-1—a lesser-known virus from the same retrovirus family as HIV-1—due to a limited understanding of its architecture.

HTLV-1 is somewhat the overlooked cousin of HIV. It has a lower prevalence than HIV-1, yet there are many cases around the world.

Florian K. M. Schur, corresponding author

Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA)

Klosterneuburg, Austria.

According to the World Health Organization, between 5 and 10 million people are currently living with HTLV-1. While most of the infections remain asymptomatic, roughly 5% lead to aggressive diseases like adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma—a form of cancer with a prognosis of less than a year.

As a human pathogen causing severe diseases, HTLV-1 should be at the forefront of our research to address the questions about its functions and structure.

Martin Obr, first author

Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA)

Klosterneuburg, Austria.

The viral lattice

The scientists were particularly interested in the virus particle’s structure—information that remained elusive until now.

When a virus gets produced, it generates a particle. This particle, however, is not yet infectious. The immature virus particle must undergo a maturation process to become infectious.

Florian K. M. Schur.

The HTLV-1 particle is shaped by a lattice of proteins (building blocks) arranged into a spherical shell. This shell serves a critical function: it protects the viral genetic material until the host cell is infected. But what does this lattice look like in detail, what are its key components, and does it vary from other viruses?

We were expecting a difference from other viruses, but the extent of it completely blew us away. From an evolutionary standpoint, it was probably advantageous for HTLV-1 to change its lattice structure for this kind of transmission. Nevertheless, at this point, it is only speculation. It needs to be experimentally verified.

Martin Obr.

A unique virus

The scientists’ analysis revealed that the lattice of immature HTLV-1 is remarkably distinct from other retroviruses. Its building blocks are put together in a unique fashion, and as a result, its overall architecture looks different. Additionally, the ‘glue’ that holds the construct together also differs. In most retroviruses, the lattice consists of a top and a bottom layer; typically, the bottom layer acts as the glue, maintaining structural integrity, while the top layer defines the shape.

In HTLV, it’s the other way around. The bottom layer is basically just hanging by a thread.

Florian K. M. Schur.

Naturally, the question of why HTLV-1 has such a different lattice architecture arises. A possible explanation might be that HTLV-1 has a unique way of transmission. HTLV-1 prefers to have one infected cell next to an uninfected one to spread with direct contact. HIV-1, on the other hand, uses cell-free transmission. It produces particles that can travel anywhere in the bloodstream.

New treatment strategies? A schematic of the assembly of viral particles. Top: HTLV-1. The top layer (blue) organizes the immature lattice. Bottom: Other retroviruses (e.g. HIV-1). The bottom layer (orange) organizes the immature lattice.© Nature Structural & Molecular Biology/Obr et al.

A schematic of the assembly of viral particles. Top: HTLV-1. The top layer (blue) organizes the immature lattice. Bottom: Other retroviruses (e.g. HIV-1). The bottom layer (orange) organizes the immature lattice.© Nature Structural & Molecular Biology/Obr et al.

Understanding these structural details is a crucial step forward, as the paper could pave the way for novel treatment approaches to combat HTLV-1 infections.

There are different ways to interfere with retrovirus infectivity. For example, one could block the mature virus at the stage of infection. Alternatively, one could target the immature virus and prevent it from maturing and becoming infectious. Since the scientists’ study details the architecture of the immature virus, one can now think of strategies for tackling the virus during this stage of its maturation.

There are types of viral inhibitors that disrupt the assemblies by targeting the building blocks to prevent them from coming together. Others work by destabilizing the lattice. There are many possibilities.

Florian K. M. Schur.

The perfect ‘ice cold’ sample

Despite their experience analyzing viruses of the same family, such as HIV-1, the team’s current research project on HTLV-1 brought its unique challenges. Obr’s “perfect sample” was the turning point.

Due to safety reasons, the sample does not contain the actual virus. Instead, the scientists produced viral-like particles in mammalian cell cultures or generated the viral building blocks in bacterial cultures.

When these building blocks are placed in the correct conditions, they self-assemble into structures that resemble the actual immature virus.

Florian K. M. Schur.

These non-infectious particles are then rapidly frozen, stored at -196 °C in liquid nitrogen, and eventually imaged using a Cryo-Electron Microscope (Cryo-EM)—a type of microscope that captures high-resolution images down to a nanometer.

Samples are dipped into cryogen or liquid ethane. Rapid cooling causes the water in the sample to vitrify, meaning it turns into a glass-like form instead of forming ice crystals. This state preserves the fine structural details of the sample.

A valid concern, as Obr notes, “Our virus-like particles only lack a few enzymes that would help them to mature. There is no reason to think the real immature particle does look different.” This careful approach, however, ensures that researchers can study viruses safely while still gaining invaluable insights.

Publication:M. Obr, M. Percipalle, D. Chernikova, H. Yangamp;, A. Thader, G. Pinke, D. Porley, L. M. Mansky, R. A. Dick & F. K. M. Schur. 2024.

Distinct stabilization of the human T cell leukemia virus type immature Gag lattice. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. DOI: 10.1038/s41594-024-01390-8

AbstractIt seems to be a characteristic of creationists to compartmentalize their thinking so they can hold two or more mutually contradictory views simultaneously. On the one hand, they insist that only their god has the power to create living organisms, so they attribute all the good things to it and declare it to be an omnipotent, all-loving god who works to maximise the happiness and minimise the suffering in the world. On the other hand, something else also has the power to create parasites and all the nasty things that, when attributed to their putative designer, makes it look like a pestilential monster who designs ways to minimise the happiness and maximise the suffering in the world.

Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) immature particles differ in morphology from other retroviruses, suggesting a distinct way of assembly. Here we report the results of cryo-electron tomography studies of HTLV-1 virus-like particles assembled in vitro, as well as derived from cells. This work shows that HTLV-1 uses a distinct mechanism of Gag–Gag interactions to form the immature viral lattice. Analysis of high-resolution structural information from immature capsid (CA) tubular arrays reveals that the primary stabilizing component in HTLV-1 is the N-terminal domain of CA. Mutagenesis analysis supports this observation. This distinguishes HTLV-1 from other retroviruses, in which the stabilization is provided primarily by the C-terminal domain of CA. These results provide structural details of the quaternary arrangement of Gag for an immature deltaretrovirus and this helps explain why HTLV-1 particles are morphologically distinct.

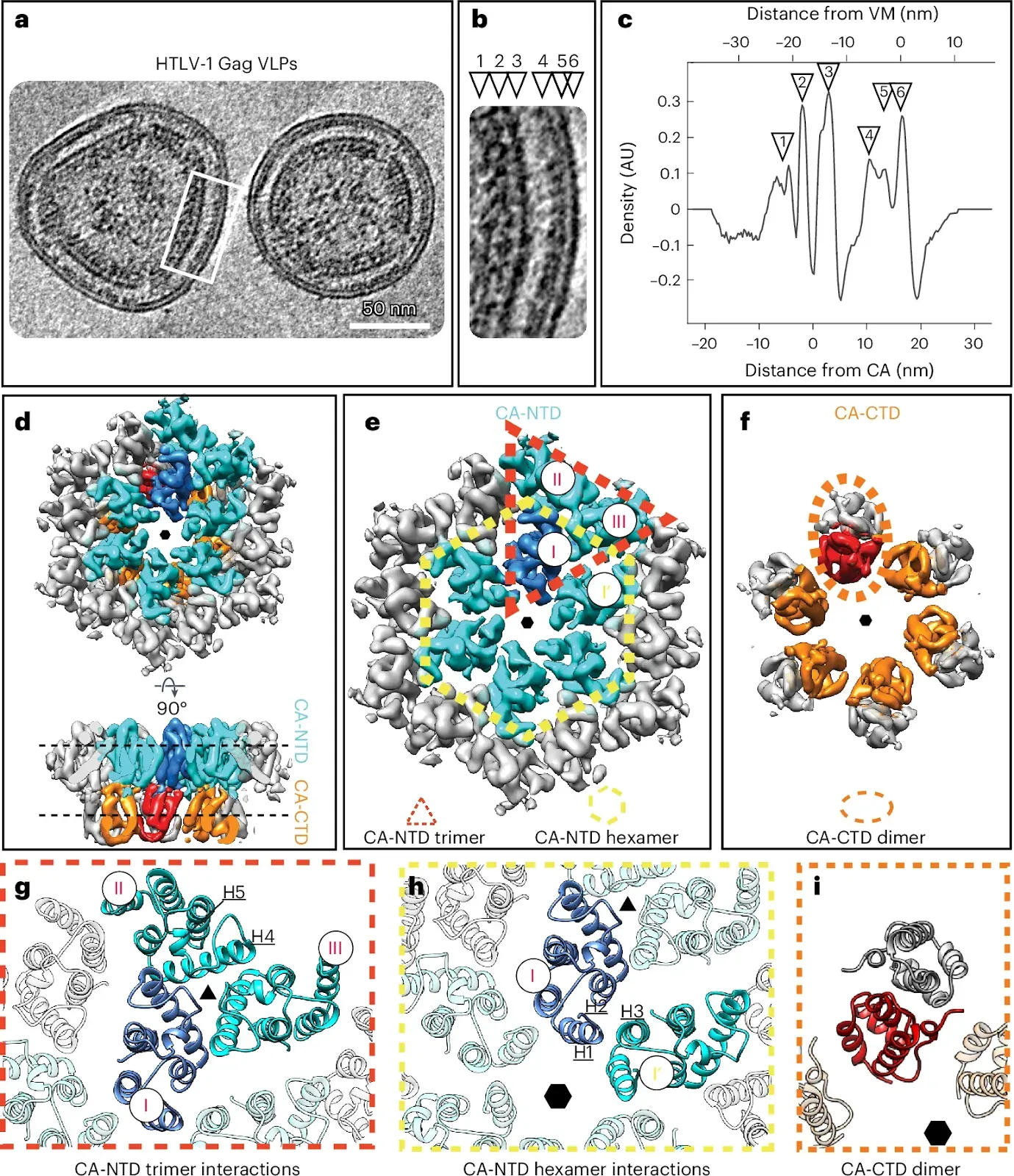

Fig. 1: Cryo-ET of immature HTLV-1 Gag VLPs. a, Computational slice (thickness, 8.8 nm) through a cryo-electron tomogram containing HTLV-1 Gag-based VLPs. Protein density is black. Scale bar, 50 nm. The shown tomogram is representative of the 85 tomograms acquired. b, Enlarged view of the Gag lattice within VLPs, as annotated by a white rectangle in a. The arrowheads designate the different layers of the radially aligned Gag lattice underneath the viral membrane (VM): NC-RNP (1), CA-CTD (2), CA-NTD (3), MA (4), inner leaflet (5) and outer leaflet (6). c, The 1D radial density plot of the Gag lattice in immature HTLV-1 Gag-based VLPs. Two zero-value reference points are reported for the distance measurement. The primary x axis reference zero value is set at the VM (top x axis). The secondary x axis reference zero value is set at the local density minimum between the CA-NTD and CA-CTD (bottom x axis) and is provided to allow a straightforward comparison to Fig. 2c. The distance of the different layers from these reference points is given in nanometers. The annotation with arrowheads is as in b. AU, arbitrary units. d–f, Isosurface representations of the subtomogram average of the CA hexamer from HTLV-1 Gag-based VLPs. The CA-NTDs of the central hexamer are colored cyan, with one monomer highlighted in blue. Two additional CA-NTD monomers from adjacent hexamers are also colored in cyan, to highlight the trimeric interhexamer interface. The CA-CTDs of the central hexamer are colored orange and red. The hexameric arrangement is indicated by a small hexagon. d, CA lattice as seen from the outside of the VLP and rotated by 90° to show a side view. e, Top view of the CA-NTD, with the trimeric interhexamer interface and the intrahexameric interface indicated with a dashed red triangle and dashed yellow hexagon, respectively. CA monomers in the trimeric interhexamer interface are annotated with I, II and III. f, Top view of the CA-CTD hexamer. A dashed orange ellipsoid highlights one CA-CTD dimer linking adjacent hexamers. g,h, Molecular models of the CA-NTD and CA-CTD rigid-body fitted into the EM density of the immature CA lattice. Coloring as in d–f. g, Trimeric CA-NTD interactions linking hexamers, involving residues spanning helices 4 and 5. h, Interactions around the hexamer, involving helices 1, 2 and 3 from adjacent CA-NTDs. i, Model of the CA-CTD dimer.Obr, M., Percipalle, M., Chernikova, D. et al.

a, Computational slice (thickness, 8.8 nm) through a cryo-electron tomogram containing HTLV-1 Gag-based VLPs. Protein density is black. Scale bar, 50 nm. The shown tomogram is representative of the 85 tomograms acquired. b, Enlarged view of the Gag lattice within VLPs, as annotated by a white rectangle in a. The arrowheads designate the different layers of the radially aligned Gag lattice underneath the viral membrane (VM): NC-RNP (1), CA-CTD (2), CA-NTD (3), MA (4), inner leaflet (5) and outer leaflet (6). c, The 1D radial density plot of the Gag lattice in immature HTLV-1 Gag-based VLPs. Two zero-value reference points are reported for the distance measurement. The primary x axis reference zero value is set at the VM (top x axis). The secondary x axis reference zero value is set at the local density minimum between the CA-NTD and CA-CTD (bottom x axis) and is provided to allow a straightforward comparison to Fig. 2c. The distance of the different layers from these reference points is given in nanometers. The annotation with arrowheads is as in b. AU, arbitrary units. d–f, Isosurface representations of the subtomogram average of the CA hexamer from HTLV-1 Gag-based VLPs. The CA-NTDs of the central hexamer are colored cyan, with one monomer highlighted in blue. Two additional CA-NTD monomers from adjacent hexamers are also colored in cyan, to highlight the trimeric interhexamer interface. The CA-CTDs of the central hexamer are colored orange and red. The hexameric arrangement is indicated by a small hexagon. d, CA lattice as seen from the outside of the VLP and rotated by 90° to show a side view. e, Top view of the CA-NTD, with the trimeric interhexamer interface and the intrahexameric interface indicated with a dashed red triangle and dashed yellow hexagon, respectively. CA monomers in the trimeric interhexamer interface are annotated with I, II and III. f, Top view of the CA-CTD hexamer. A dashed orange ellipsoid highlights one CA-CTD dimer linking adjacent hexamers. g,h, Molecular models of the CA-NTD and CA-CTD rigid-body fitted into the EM density of the immature CA lattice. Coloring as in d–f. g, Trimeric CA-NTD interactions linking hexamers, involving residues spanning helices 4 and 5. h, Interactions around the hexamer, involving helices 1, 2 and 3 from adjacent CA-NTDs. i, Model of the CA-CTD dimer.Obr, M., Percipalle, M., Chernikova, D. et al.

Distinct stabilization of the human T cell leukemia virus type 1 immature Gag lattice. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-024-01390-8

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

And yet, in a world controlled by an omnipotent, omnibenevolent god, it should not be possible to create organisms such as the HIV and HTLV-1 virus, or any parasite for that matter, which appear to exist only to create more of themselves, in order to maximise suffering and minimise happiness, unless the god wants them to be created. And such a god can’t be both omnipotent and omnibenevolent. The best that can be said of it is that it is indifferent and uncaring.

Only by deliberately dishonest double-think can creationists hold these two views simultaneously whilst avoiding thinking about the contradiction and inconsistency in their beliefs.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Obscene, threatening or obnoxious messages, preaching, abuse and spam will be removed, as will anything by known Internet trolls and stalkers, by known sock-puppet accounts and anything not connected with the post,

A claim made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Remember: your opinion is not an established fact unless corroborated.