The virus that causes COVID-19 is widespread in wildlife, Virginia Tech scientists find | Virginia Tech News | Virginia Tech

If you've got money to invest, don't invest it all in one product. If that product fails you lose everything, so spread it around, that way you're reducing your risk and should have something left even if your main investment crashes. In other words, don't have all your eggs in one basket.

And Creationism's malevolent designer, who invested heavily in the SARS-CoV-2 virus as its preferred way to make people sick and die and to ruin national economies on a world-wide scale, understands that principle well. But the problem is, humans fought back and not only invented an effective vaccine that cut down the malevolence’s return on investment, but they also developed immunity which reduces the death toll down to a mere headache and feeling a bit lethargic for a few days.

Do you have any information on how many other species can also be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus? Yes, many other species can be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the virus responsible for COVID-19 in humans. Research has identified several animals that can be naturally or experimentally infected. Here is an overview of some of the species known to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2:By the divine malevolence was crafty and hedged its bets by designing the virus so it also infects wild animals so it can build up a nice little nest egg with which to launch another big raid on the futures market which could pay dividends in terms of human lives and increased suffering. All it need do is give the virus a little tweak and we could have another pandemic to rival the 2020 one all over again.

The list of species continues to evolve as more research is conducted. Surveillance and studies are ongoing to better understand the range of susceptible species, their role in the transmission of the virus, and the potential implications for human and animal health.

- Domestic Animals:

- Cats: Both domestic and big cats (like lions and tigers in zoos) have been infected. Cats can also transmit the virus to each other.

- Dogs: Some dogs have tested positive, but they generally show no or mild symptoms.

- Ferrets: Highly susceptible and can transmit the virus to other ferrets.

- Mink: Infected minks have been found on farms, with some cases leading to large outbreaks and human infections.

- *Wildlife:

- Big Cats: Lions, tigers, snow leopards, and cougars in zoos have contracted the virus.

- White-tailed Deer: Studies have shown that these deer can be infected and spread the virus among themselves.

- Non-Human Primates: Various species of monkeys, such as rhesus macaques, cynomolgus macaques, and marmosets, can be infected and exhibit symptoms similar to humans.

- Laboratory Animals:

- Hamsters: Both Syrian and Chinese hamsters are susceptible and can transmit the virus.

- Mice: Wild-type mice are generally not susceptible, but genetically modified mice expressing the human ACE2 receptor can be infected.

- Rabbits: Some susceptibility has been observed, although with mild or no symptoms.

- Tree Shrews: Can be infected and are used in research studies.

- Farm Animals:

- Pigs: Some studies have shown low susceptibility with no significant symptoms.

- Cows** and **Chickens: Generally considered not susceptible based on current evidence.

We have known about the zoonotic abilities of the virus for some time - after all it is believed to have evolved in another species before transferring to humans in 2019, but a team of Virginia Tech researchers have discovered that it may be more widespread in the wild animal populations, especially those near human habitation, than was previously thought.

Their results are published, open access in the journal Nature Communications and are explained in a Virginia Tech news release:

The virus that causes COVID-19 is widespread in wildlife, Virginia Tech scientists findDetails of the carrier species appear in the team's open access paper on Nature Communications:

Six of 23 common wildlife species showed signs of SARS-CoV-2 infections in an examination of animals in Virginia, as revealed by tracking the virus’s genetic code.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, is widespread among wildlife species, according to Virginia Tech research published today in Nature Communications. The virus was detected in six common backyard species and antibodies indicating prior exposure to the virus were found in five species with rates of exposure ranging from 40 to 60 percent depending on the species.

Genetic tracking in wild animals confirmed both the presence of SARS-CoV-2 and the existence of unique viral mutations with lineages closely matching variants circulating in humans at the time, further supporting human-to-animal transmission, the study found.

The highest exposure to SARS CoV-2 was found in animals near hiking trails and high-traffic public areas, suggesting the virus passed from humans to wildlife, according to scientists at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, the Department of Biological Sciences in Virginia Tech’s College of Science, and the Fralin Life Sciences Institute.

The findings highlight the identification of novel mutations in SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife and the need for broad surveillance. These mutations could be more harmful and transmissible, creating challenges for vaccine development.

The scientists stressed, however, that they found no evidence of the virus being transmitted from animals to humans, and people should not fear typical interactions with wildlife.

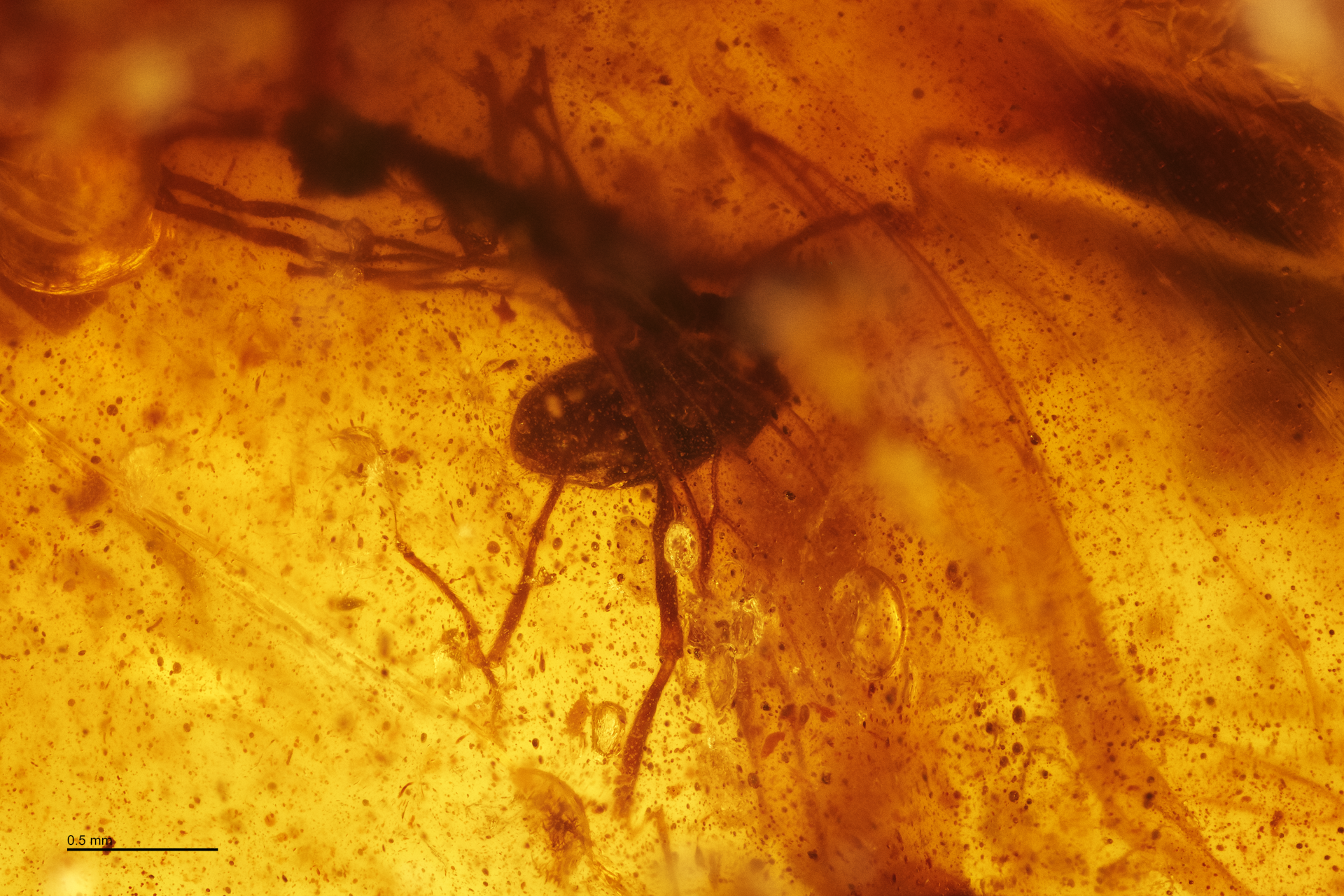

Investigators tested animals from 23 common Virginia species for both active infections and antibodies indicating previous infections. They found signs of the virus in deer mice, Virginia opossums, raccoons, groundhogs, Eastern cottontail rabbits, and Eastern red bats. The virus isolated from one opossum showed viral mutations that were previously unreported and can potentially impact how the virus affects humans and their immune response.

The virus can jump from humans to wildlife when we are in contact with them, like a hitchhiker switching rides to a new, more suitable host. The goal of the virus is to spread in order to survive. The virus aims to infect more humans, but vaccinations protect many humans. So the virus turns to animals, adapting and mutating to thrive in the new hosts.

Professor Carla Finkielstein, Co-corresponding author

Professor of biological sciences

Department of Biological Sciences

Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

SARS CoV-2 infections were previously identified in wildlife, primarily in white-tailed deer and feral mink. The Virginia Tech study significantly expands the number of species examined and the understanding of virus transmission to and among wildlife. The data suggests exposure to the virus has been widespread in wildlife and that areas with high human activity may serve as points of contact for cross-species transmission.The research team collected 798 nasal and oral swabs across in Virginia from animals either live-trapped in the field and released, or being treated by wildlife rehabilitation centers. The team also obtained 126 blood samples from six species. The locations were chosen to compare the presence of the virus in animals in sites with varying levels of human activity, from urban areas to remote wilderness.This study was really motivated by seeing a large, important gap in our knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 transmission in a broader wildlife community. A lot of studies to date have focused on white-tailed deer while what is happening in much of our common backyard wildlife remains unknown.

Assistant Professor Joseph R. Hoyt, co-corresponding author

Assistant professor of biological sciences

Department of Biological Sciences

Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

The study also identified two mice at the same site on the same day with the exact same variant, indicating they either both got it from the same human, or one infected the other.

Researchers are not certain about the means of transmission from humans to animals. One possibility is wastewater, but the Virginia Tech scientists believe trash receptacles and discarded food are more likely sources.While this study focused on the state of Virginia, many of the species that tested positive are common backyard wildlife found throughout North America. It is likely they are being exposed in other areas as well, and surveillance across a broader region is urgently needed, Hoyt said.I think the big take home message is the virus is pretty ubiquitous. We found positives in a large suite of common backyard animals.

Dr Amanda R. Goldberg, first author

Department of Biological Sciences

Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA.The virus is indifferent to whether its host walks on two legs or four. Its primary objective is survival. Mutations that do not confer a survival or replication advantage to the virus will not persist and will eventually disappear. We understood the critical importance of sequencing the genome of the virus infecting those species. It was a monumental task that could only be accomplished by a talented group of molecular biologists, bioinformaticians, and modelers in a state-of-the-art facility. I am proud of my team and my collaborators, their professionalism, and everything they contributed to ensure our success.

Professor Carla Finkielstein.

The Roanoke lab was established in April 2020 to expand COVID-19 testing.

Scientists should continue surveillance for these mutations and not dismiss them, the scientists said. More research is needed about how the virus is transmitted from humans to wildlife, how it might spread within a species, and perhaps from one species to another.This study highlights the potentially large host range SARS-CoV-2 can have in nature and really how widespread it might be. There is a lot of work to be done to understand which species of wildlife, if any, will be important in the long-term maintenance of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.

Assistant Professor Joseph R. Hoyt.The team will continue its research supported by a $5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.But what we’ve already learned is that SARS CoV-2 is not only a human problem and that it takes a heck of a multidisciplinary team to address its impact on various species and ecosystems effectively.

Professor Carla Finkielstein.

Other authors on the paper include:

- Kate Langwig, associate professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Fralin Life Sciences Institute

- James Weger-Lucarelli, assistant professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

- Anne Brown, associate professor, Department of Biochemistry

- Amanda Goldberg, former postdoctoral associate, Department of Biological Sciences

- Jeffrey Marano, graduate research assistant, Department of Biological Sciences

- Pallavi Rai, graduate research assistant, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

- Kelsi King, graduate research assistant, Genetics, Bioinformatics, and Computational Biology

- Amanda Sharp, graduate research assistant, Genetics, Bioinformatics, and Computational Biology

- Christopher Kailing, graduate research assistant, Department of Biological Sciences

- Macy Kailing, graduate research assistant, Department of Biological Sciences

- Members of the Virginia Tech Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory: Katherine L. Brown, Alessandro Ceci, Russell Briggs, Matthew G. Urbano, Clinton Roby

Abstract

Pervasive SARS-CoV-2 infections in humans have led to multiple transmission events to animals. While SARS-CoV-2 has a potential broad wildlife host range, most documented infections have been in captive animals and a single wildlife species, the white-tailed deer. The full extent of SARS-CoV-2 exposure among wildlife communities and the factors that influence wildlife transmission risk remain unknown. We sampled 23 species of wildlife for SARS-CoV-2 and examined the effects of urbanization and human use on seropositivity. Here, we document positive detections of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in six species, including the deer mouse, Virginia opossum, raccoon, groundhog, Eastern cottontail, and Eastern red bat between May 2022–September 2023 across Virginia and Washington, D.C., USA. In addition, we found that sites with high human activity had three times higher seroprevalence than low human-use areas. We obtained SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequences from nine individuals of six species which were assigned to seven Pango lineages of the Omicron variant. The close match to variants circulating in humans at the time suggests at least seven recent human-to-animal transmission events. Our data support that exposure to SARS-CoV-2 has been widespread in wildlife communities and suggests that areas with high human activity may serve as points of contact for cross-species transmission.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has resulted in over 771 million human cases and over six million deaths worldwide1. As SARS-CoV-2 becomes endemic in humans, one of the greatest threats to public health is the resurgence of more virulent and transmissible variants. The considerable pathogen pressure imposed by the pandemic has caused concern as to whether SARS-CoV-2 will spill into wildlife populations, establish a sylvatic cycle, and potentially serve as a source for new variants.

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to captive animals has been well documented2,3,4, but detections in free-ranging wildlife are currently limited to only a few species including white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus5,6,7), feral mink (Neovison vison8), and Eurasian river otters (Lutra lutra9). Experimental infections and modeling of the functional receptor for SARS-CoV-2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: ACE2) have shown that numerous wildlife species may be competent hosts10,11,12,13,14,15. However, it remains unexplored whether a diversity of wildlife species are infected in natural settings, where exposure to SARS-CoV-2 is likely to be indirect and at a lower exposure dose.

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in 2019, numerous variants have been detected in humans and animals. Many variants that have become dominant have mutations that increase their infectivity in humans16, and may also impact the virus’s ability to infect new wildlife species. SARS-CoV-2 collected from white-tailed deer have included lineages circulating in humans, caused by human-to-deer transmission5, but have also included lineages with unique mutations suggestive of deer-to-deer transmission17. This implies that only minimal adaptation may be needed for transmission to occur among deer following initial human-to-animal transmission events18. Other human peridomestic species, such as deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus)12,13 and skunks (Mephitis mephitis)14 have been shown to be capable of viral shedding in laboratory settings11. Collectively, these studies raise important questions about the extent of human-to-wildlife transmission and the ability of other wildlife species to sustain transmission.

Establishment of SARS-CoV-2 infections in wildlife communities could result in novel mutations that increase virulence, transmissibility, or confer immune escape, negatively impacting both human and wildlife populations. Furthermore, as SARS-CoV-2 adapts to not only human hosts, but potentially a wide diversity of wildlife species, SARS-CoV-2 evolution may become more unpredictable19. This could present several challenges for human health, including concerns related to vaccine development targeting human-specific lineages, and novel impacts to pathogenicity and transmissibility of the virus.

Here, we examine how widespread SARS-CoV-2 exposure has been in wildlife communities between May 2022 and September 2023. We used quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to examine 789 nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal samples from 23 species sampled across Virginia and Washington D.C., USA and documented the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in six of these species. In addition, we analyzed 126 serum samples from six species collected before and after the arrival of SARS-CoV-2 and detected neutralizing antibody titers in five of the six species. Finally, we detected an effect of urbanization and human use on seropositivity in animals, and examined genomic data associated with positive samples.

Goldberg, A.R., Langwig, K.E., Brown, K.L. et al.

Widespread exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife communities. Nat Commun 15, 6210 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49891-w

Copyright: © 2024 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access.

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

The fact that this virus is so capable of infecting other species is a cause for concern because the wider it spreads and the more species it come into contact with, the greater the chance of it crossing over to new species, and the more species it infects, the greater the probability of new variants evolving that can transfer back into humans with unpredictable consequences.

Creationists must be very proud of the devious nastiness of their favorite malevolence.